| Source (Hebrew) | Translation (English) |

|---|---|

[… אנכי י]הוה אלהיך אשר [הוצא]תיך מארץ מ[צרים] |

[I am Y]HVH your elo’ah that [brought] you out of the land of M[istrayim:] |

[לוא יהיה ל]ך אלהים אחרים [על פ]ני לוא תעשה [לך פסל] [וכל תמונה] אשר בשמים ממעל ואשר בארץ [מתחת] [ואשר במי]ם מתחת לארץ לוא תשתחוה להם [ולוא] [תעבדם כי] אנכי יהוה אלהיך אל קנוא פק[ד עון] [אבות על בני]ם על שלשים ועל רבעים לשנאי[ועשה] [חסד לאלפים] לאהבי ולשמרי מצותי |

[You shall not hav]e other elohim be[fore] me. You shall not make [for yourself an image] [or any form] that is in the heavens above, or that is in the earth [beneath,] [or that is in the water]s beneath the earth. You shall not bow down to them [nor] [serve them, for] I am YHVH your elo’ah, a jealous el visi[ting the iniquity] [of fathers upon son]s to the third and to the fourth generation unto them that hate me, [and doing] [kindness unto thousands] unto them that love me and keep my commandments. |

לוא ת[שא את] [שם יהוה א]להיך לשוא כי לוא ינקה יהוה [את אשר] [ישא את ש]מה לשוא |

You shall [not] [take up the name of YHVH] your elo’ah in vain, for YHVH will not hold guiltless [him that] [take up his n]ame in vain. |

זכור את יום השבת [לקדשו] [ששת ימי]ם תעבוד ועשית כל מלאכתך וביום [השביעי] [שבת ליהוה] אלהיך לוא תעשה בה כל מלאכה [אתה] [ובנך ובתך] עבדך ואמתך שורך וחמרך וכל ב[המתך] [וגרך אשר] בשעריך כי ששת ימים עשה י[הוה] [את השמי]ם ואת הארץ את הים ואת כל א[שר בם] וינח [ביום] השביעי עלכן ברך יהוה את [יום] השביעי ויקדשיו |

Remember the day of the Shabbat [to hallow it:] [six day]s You shall work and do all your handicraft, and on the [seventh day,] [a Shabbat for YHVH] your elo’ah, You shall not do therein any handicraft, [You] [and your son and your daughter,] your slave and your handmaid, your ox and your donkey and all your [domesticated animals,] [and your stranger that is] in your gates. For six days did Y[HVH make] [the heaven]s and the earth, the sea and all th[at is therein,] and he rested [on the] seventh day; therefore YHVH blessed [the] seventh day and hallowed it. |

כבד את אביך ואת אמ[ך למען] ייטב לך ולמען יאריכון ימיך על האדמה [אשר] יהוה אלהיך נתן לך |

Honor your father and your mothe[r, that] it may be well with you and that your days may be long upon the ground [that] YHVH your elo’ah gives you. |

לוא תאנף |

You shall not do adultery. |

לוא תרצח |

You shall not do murder. |

לו[א] [תג]נב |

You shall [not] [st]eal. |

לוא ת[ע]נה ברעך עד שוא |

You shall not [bear] against your neighbor false witness. |

לוא תחמוד [את] [אשת רעך] |

You shall not covet [the] [wife of your neighbor.] |

[ל]וא תת[א]וה את ב[י]ת רעך שד[הו ועבדו] [ואמתו וש]ורו וחמרו וכל אשר לרעך [blank] |

[You shall] not desire the house of your neighbor, his fiel[d, or his slave,] [or his handmaid, or his o]x, or his donkey, or anything that is your neighbor’s. [blank] |

[ואלה החק]ים והמשפטים אשר צוה משה את [בני] [ישראל] במדבר בצאתם מארץ מצרים |

[(?) And these are the statute]s and the judgments that Moshe commanded the [children of] [Yisrael] in the wilderness, when they went forth from the land of Egypt. |

שמ[ע] [ישרא]ל יהוה אלהינו יהוה אחד הוא |

Hea[r] [Yisra]el: YHVH our elo’ah, YHVH is inimitable; |

וא[הבת] [את יהוה א]ל[היך בכ]ל ל[בבך. . . . ] |

and You shall lo[ve] [YHVH your el]o[ah with al]l y[our heart … . ]. |

This is a digital transcription of F.C. Burkitt’s published transcription of the Decalogue and the opening of the Shema from the Nash Papyrus.[1] F.C. Burkitt, “The Hebrew Papyrus of the Ten Commandments,” The Jewish Quarterly Review, 15, 392-408 (1903) . Text in brackets is reconstructed based on the the surrounding text, space to margin, and comparative sources.

Once upon a time, according to the Mishnah, it was the nusaḥ (liturgical tradition) of the Cohanim in the Bet Hamikdash[2] Priests of the Temple in Jerusalem for the Ten Commandments to be read prior to the Sh’ma. Here’s the relevant teaching from Mishnah Tamid (32b in Talmud Bavli Tamid), emphasis mine:

מתני׳ אמר להם הממונה ברכו ברכה אחת והם ברכו קראו עשרת הדברות שמע והיה אם שמוע ויאמר ברכו את העם שלש ברכות אמת ויציב ועבודה וברכת כהנים ובשבת מוסיפין ברכה אחת למשמר היוצא: |

The appointed one (i.e., the deputy high priest) said to them (the priests), pronounce one blessing, and they did so. And they then recited the Ten Commandments, and the Shema (‘And it shall come to pass if you diligently follow’, and ‘And YHVH said’) and recited with the people three blessings (‘True and firm’, the blessing of the ‘Avodah, and the Priestly Blessing) [in the Amidah]. On Shabbat they said an additional blessing for the outgoing watch. |

So, why don’t we read the Ten Commandments during the Shaḥarit (morning service) today? Sadly, fears over the insinuations made by certain Minim (a category of heretics), left this practice confined to the age of the Temple. No one was able to revive this custom regardless of the evident surviving passion for it shown by generations of Babylonian Amoraim.

א״ר יהודה אמר שמואל אף בגבולין בקשו לקרות כן אלא שכבר בטלום מפני תרעומת המינין תניא נמי הכי ר׳ נתן אומר בגבולין בקשו לקרות כן אלא שכבר בטלום מפני תרעומת המינין רבה בב״ח סבר למקבעינהו בסורא א״ל רב חסדא כבר בטלום מפני תרעומת המינין אמימר סבר למקבעינהו בנהרדעא א״ל רב אשי כבר בטלום מפני תרעומת המינין: |

Rabi Yehudah[3] Rabi Yehuda ben Ilai, a third generation Tanna of the 2nd Century C.E. said in the name of Shmuel[4] Shmuel haKatan, a second generation Tanna from the 1st century C.E. At the behest of Rabi Gamliel II of Yavneh, he wrote the Birkat HaMinim, by tradition the 19th and final blessing composed for the Amidah (also known as the Shmonah Esrei, the 18 [blessings]). Less a blessing than a curse, Shmuel attempted to end the blessing but it proved resilient and remains part of the liturgy of the Amidah today. : Outside the Temple people also wanted to do the same (i.e. say the Ten Commandments before the Sh’ma) but they were stopped on account of the insinuations of the Minim[5] A category of heretic in Jewish law [that the Ten Commandments were the only valid part of the Torah]. Similarly it has been taught: Rabi Natan[6] Rabi Natan HaBavli, a third generation Tanna of the 2nd Century C.E. says, They sought to do the same outside the Temple, but it had long been abolished on account of the insinuations of the Minim. Rabbah bar Bar Ḥanah[7] Rabbah bar Bar Ḥanah, a second generation Amorah in Babylonia (circa 250-280 C.E.) had an idea of instituting this in Sura,[8] Sura, home to an important Babylonian yeshiva (talmudic academy) but Rav Ḥisda[9] Rav Ḥisda (228-320 C.E.), an Amora of the third generation said to him, It had long been abolished on account of the insinuations of the Minim. Ameymar[10] Ameymar, an Babylonian Amora of the fifth or sixth generation (380-410 C.E.) had an idea of instituting it in Nehardea,[11] Nehardea, home to an important Babylonian yeshiva but Rav Ashi[12] Rav Ashi, (352-427 C.E.) a sixth generation Babylonian Amora said to him, It had long been abolished on account of the insinuations of the Minim.[13] Talmud Bavli, Berakhot 12a. Also see Talmud Yerushalmi Berakhoth, i. 8 (4) |

By the time Rav Saadya Gaon and Rav Amram helped to set down the liturgy in print, this liturgical custom had been relegated to the age of the Temple (before 70 C.E.). This wasn’t the first time a liturgical custom had been left to this era. As Rabbi Mark Sameth explains:

The Tetragrammaton [the four-letter divine name used in the Torah, aka, the shem hameforash) was permitted for everyday greetings until at least 586 B.C.E., when the First Temple was destroyed (Mishnah Berakhot 9:5). In time its pronunciation was permitted only to the priests (Mishnah Sotah 7:6), who would pronounce it in their public blessing of the people. With the death of the High Priest Shimon HaTzaddik circa 300 BCE (Talmud Bavli, Yoma 39b) the Name was pronounced only by the High Priest in the Holy of Holies on Yom Kippur (see Mishnah, Sotah 7:6; Mishnah, Tamid 7:2). According to the Zohar, “the ineffable Name was openly enunciated in the hearing of all, but after irreverence became widespread it was concealed under other letters” (Zohar, Bamidbar Naso 146b). According to the Talmud, the pronunciation was passed on by the sages to their disciples only once (some say twice) every seven years (Talmud Bavli, Kiddushin 71a). Finally, upon the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 C.E., the Name was no longer pronounced at all.[14] Rabbi Mark Sameth, “The Secret Four-Letter Name of God,” CCAR Journal Summer 2008, p.27, cf., 10.

Nor are these examples unique to the history of Jewish spiritual practice. Concerns over how liturgy was heard or misheard, understood or misunderstood, abused irreverently or used to incite fear and prejudice, produced a fair amount of liturgical variation between nusḥaot. These variations reflect regions in which Jewish communities struggled under oppression and censorship even unto the 20th century.

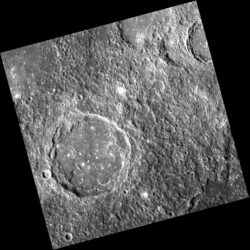

But back to the reciting of the Ten Commandments prior to the Sh’ma. Quite remarkably, in 1898 an ancient papyrus manuscript was purchased from an antiquities merchant in Egypt that attests to this tradition. On the papyrus is recorded the Ten Commandments followed by the Sh’ma. Named the Nash Papyrus after the man W.L. Nash who purchased it and then brought it to Cambridge University Library, the manuscript witnesses what is likely the oldest extant work of Jewish liturgy. Scholars dated it somewhere between 150 and 100 BCE. What continues to fascinate scholars is how this text, early enough to predate the fixed Masoretic text familiar to Judaism, corresponds to very early editions of the Torah only preserved in translation.

Twenty four lines long, with a few letters missing at each edge, the papyrus contains the Ten Commandments in Hebrew, followed by the start of the Sh’ma prayer. The text of the Ten Commandments combines parts of the version from Exodus 20:2-17 with parts from Deuteronomy 5:6-21. A curiosity is its omission of the phrase “house of bondage”, used in both versions, about Egypt – perhaps a reflection of where the papyrus was composed.

Some (but not all) of the papyrus’ substitutions from Deuteronomy are also found in the version of Exodus in the ancient Greek Septuagint translation of the Hebrew Bible. The Septuagint also interpolates before Deuteronomy 6:4 the preamble to the Sh’ma found in the papyrus, and additionally agrees with a couple of the other variant readings where the papyrus departs from the standard Hebrew Masoretic text. The ordering of the later commandments in the papyrus (Adultery-Murder-Steal, rather than Murder-Adultery-Steal) is also that found in most texts of the Septuagint, as well as in the Christian Gospels (Mark 10:19, Luke 18:20, Romans 13:9, and James 2:11, but not Matthew 19:18).

It is thus believed that the papyrus was probably drawn from a liturgical document, which may have purposely synthesised the two versions of the Commandments, rather than directly from Scripture. However, the similarities with the Septuagint text give strong evidence for the likely closeness of the Septuagint as a translation of a Hebrew text of the Pentateuch extant in Egypt in the 2nd century BCE that differed significantly from the texts later collated and preserved by the Masoretes.[15] ”Nash Papayrus,” wikipedia, accessed 2011-01-21.

What makes this manuscript fascinating to me is that the Nash Papyrus and the liturgy it witnesses, presents a novel example of a remix. By placing the two different texts next to each other in sequence, a novel association is evoked. A narrative is… reenacted.

As I imagine it, the current Shacharit (morning) practice follows the following thematic journey: liberation from the land of Constriction/mitzrayim (awareness blessings upon waking), songs of liberation until after the passage through the symplegades of standing water (psukei dzimra until az yashir), passage though a world of light and angels (i.e., the Ascent of Moshe at Har Sinai to receive the Torah[16] See “Moses and Angels” at the Encyclopedia of Jewish, Myth, Magic, and Mysticism — the blessings preceding the Sh’ma), a declaration of Oneness upon the revelation of a theophany on Earth (the Sh’ma — a meditation on the interconnectedness of transcendent One with the immanent Shem Kavod Malchuto name of God written in nature), and finally, the intimate meeting during the standing meditation of the Amidah (as the Kavod/Glory of YHVH passes before Moshe preserved in a cleft in the side of the mountain Sinai).

A recitation of the Decalogue (ten commandments) feels entirely consistent with this journey of Bnei Yisroel and Moshe, re-enacted through liturgy. It also feels a shame that even when the Temple stood, fears of irreverence mediated individual’s experience and encounters in Jewish spiritual practice. My heart is with Ameymar and Rabbah bar Bar Ḥanah in restoring this liturgy.

Sources

Notes

| 1 | F.C. Burkitt, “The Hebrew Papyrus of the Ten Commandments,” The Jewish Quarterly Review, 15, 392-408 (1903) |

|---|---|

| 2 | Priests of the Temple in Jerusalem |

| 3 | Rabi Yehuda ben Ilai, a third generation Tanna of the 2nd Century C.E. |

| 4 | Shmuel haKatan, a second generation Tanna from the 1st century C.E. At the behest of Rabi Gamliel II of Yavneh, he wrote the Birkat HaMinim, by tradition the 19th and final blessing composed for the Amidah (also known as the Shmonah Esrei, the 18 [blessings]). Less a blessing than a curse, Shmuel attempted to end the blessing but it proved resilient and remains part of the liturgy of the Amidah today. |

| 5 | A category of heretic in Jewish law |

| 6 | Rabi Natan HaBavli, a third generation Tanna of the 2nd Century C.E. |

| 7 | Rabbah bar Bar Ḥanah, a second generation Amorah in Babylonia (circa 250-280 C.E.) |

| 8 | Sura, home to an important Babylonian yeshiva (talmudic academy) |

| 9 | Rav Ḥisda (228-320 C.E.), an Amora of the third generation |

| 10 | Ameymar, an Babylonian Amora of the fifth or sixth generation (380-410 C.E.) |

| 11 | Nehardea, home to an important Babylonian yeshiva |

| 12 | Rav Ashi, (352-427 C.E.) a sixth generation Babylonian Amora |

| 13 | Talmud Bavli, Berakhot 12a. Also see Talmud Yerushalmi Berakhoth, i. 8 (4) |

| 14 | Rabbi Mark Sameth, “The Secret Four-Letter Name of God,” CCAR Journal Summer 2008, p.27, cf., 10. |

| 15 | ”Nash Papayrus,” wikipedia, accessed 2011-01-21. |

| 16 | See “Moses and Angels” at the Encyclopedia of Jewish, Myth, Magic, and Mysticism |

“השמע ועשרת הדיברות | the Shema prefaced by the Decalogue, as found in the Nash Papyrus (ca. 2nd c. BCE)” is shared through the Open Siddur Project with a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International copyleft license.

Hello thank you for your web page.

I have searched the web to find out what is bracketed as opposed to what is not bracketed in the translation of the Nash papyrus.

If you are able to explain the difference in what is actually on the Nash papyrus and what is imposed please email me with this and please post it on your site.

The brackets are sometimes left open example [six days …

And there is no explanation of these brackets on the web other than the vague reference to words coming from the Masoretic text.

Slightly confused: Alien-X

Because the papyrus is in a fragmentary condition, not all text written on it was preserved. Still, we can infer what the Hebrew text missing likely was since the Hebrew text preserved shows Exodus 20:2-17 with parts from Deuteronomy 5:6-21 (and at the very end, Deuteronomy 6:4, and what appears to be the beginning of Deuteronomy 6:5).

The Hebrew text that appears in brackets is a best guess based on the corresponding verses in the Masoretic texts. The use of brackets to show the complete text where only a fragment is witnessed is a common convention for scholars. Because the grammar of Hebrew is different than that of English, the use of brackets in the English translation can only convey where most of the corresponding text can be inferred. For example, words possessive words like “his” or “her” appear before a noun in English but in Hebrew possessives are indicated with a suffix. Some of these suffixes appear in brackets in the Hebrew, but don’t appear in brackets in the translation, since the brackets in the translation is instead trying to convey where the end of the text becomes fragmentary.

Thank you for pointing out some brackets I missed transcribing from my transcription of F.C. Burkitt, “The Hebrew Papyrus of the Ten Commandments,” in The Jewish Quarterly Review, 15, 392-408 (1903).

And then, Britain’s Chief Rabbi Lord Sacks wrote this http://www.rabbisacks.org/covenant-conversation-5772-yitro-the-custom-that-refused-to-die/. H/T Jessica Minnen.

In the following video interview Rabbi David Bar-Hayim of Machon Shilo (http://machonshilo.org) explains the history of the Ten Commandments and Shema, and discusses if and how one may include them in one’s daily schedule:

In English and Hebrew.