I’m working on a proposal for a project that I’m calling the “Open Siddur”. The goal of the project is to bring back the creative power of t’fillah to the individual while encouraging the feeling of solidarity with and awareness of the larger Jewish community and their diversity. The draft proposal is located here. Growing up Jewish and “Orthodox”, I often heard that regardless of one’s personal gripes with this or that aspect of the tradition, it was religiously dishonest, to “pick and choose” elements from the tradition one desired to practice from those that were odious. Later in college, I heard as a tenet ascribed to the “post-modern”, that the past and culture can be plundered for inspiration and re-contextualization. This other “picking and choosing” seemed to me that, while fun, was also disrespectful and cultural appropriation, similar to how the Kabbalah was re-contextualized within medieval Christendom. But now I’m thinking that for a Judaism which is under attack by mono-culture fundamentalists, deep understanding and appreciation of Jewish worldviews can be accomplished by individuals studying and selecting and even creating new elements for their personal T’fillah (one of the last spheres where the individual still retains some creative power within the constraints of Jewish traditional discipline. The 1960s saw a movement for Jewish chavurah movements to explore creativity in Judaism as a shared experience. But what is needed, and has sorely been lacking for as long as I can see is *help* from the Siddur and the Jewish tradition itself to encourage and inspire an *individual’s* creativity. After all, the tradition is relying on the individual’s energy to maintain itself to the next generation. This is usually accomplished through a religio-ethnic sense of duty and self-righteous discipline, which yield its own simple rewards to the individual. If we are to conform for the sake of a unity in tradition, we should be aware not only of the purpose of our conformities, but also the limits of our selfless conforming. The religion must maintain and encourage space and freedom for individuality and creativity, and not limit individuality in spirituality and individual expressions to fables about revered rabbis.

Antecedents

The idea for an Open Siddur was in part inspired by Rabbi Jacob Freedman’s Polychrome Historical Haggadah (1974). Rabbi Freedman’s innovation was to clearly represent the text of the Haggadah and Siddur as aggregate texts with different authors and periods of composition. (See Freedman’s color coded legend included on a bookmark distributed with his Haggadah. In a pamphlet illustrating his vision for a Polychrome Historical Jewish Prayerbook, Rabbi Freedman wrote:

This is perhaps the first attempt to present for publication a polychrome historical prayerbook. The author herewith presents a random selection of prayers in colors merely as examples to show the various levels of historical development….The marginal symbols, also in color, indicate the period when certain prayers or phrases were first formulated and/ or introduced into the prayerbook. The references are not to be considered exhaustive.

Freedman passed away in 1986 before he could complete negotiations for the publication of his prayerbook, and tragically, his manuscript is now lost. Considering that Freedman’s use of color amounted to an early application of metadata to text, it seemed clear that a much more nuanced approach to the origin and inclusion of text in the Siddur could be supported with open source database technologies.

A couple years earlier, Reb Zalman Schachter-Shalomi described a shared digital database for new and old liturgy in an article for the Havurah newsletter, entitled “Database Davennen” (ca. 1984):

The idea is to have a central database, into which lots of people in the havurah movement can make their contribution. Many options could be included for all parts of the service, created by different people and different groups. People will add their own personal rubrics, based on their own experience. Right now we have calendar rubrics, e.g., on Monday and Thursday you don’t recite this, but we will add, “Birchot haShachar works best close to dawn,” and ways to involve the group. We don’t put it as law, but as suggestion, as a recipe. We make a big appendix to the siddur. We leave out some of the things now in the siddurs, things that are so hackneyed that you can’t put them in your mouth, but we include the ones that are good. And we might want to have a series of poems. Many poets who never think of themselves as religious poets (or even religious people), are writing poetry that is current prophesy, that is modern piyyut. We want to use that stuff for musaf, where we need one more fortissimo after k’riat ha Torah. This poetry is not the kind of thing that’s made for reading by the group, but if someone reads it well and dramatically, the congregation can say amen afterward.

The only thing missing from Reb Zalman’s idea was a licensing framework by which all participants could contribute and draw from each others work under current Copyright law. But even basic technical hurdles remained into the 2000s. The idea of an Open Siddur remained a pipe dream due to the lack of available, copyright-accessible, digitized liturgy, as well as the lack of mature technology to automate transcription of Public Domain source material (i.e., Hebrew OCR tools that recognize nikkudot and other diacritical marks).

Inspirations

What inspired the Open Siddur Project? Several related ideas. First, there is the essay “Immediatism” by Peter Lamborn Wilson, which articulates how alienation is expressed through stages of mediation, and the meaning of the term “media” in relation to both mediation and immediacy. For example, we might expect or desire prayer, of all media, to be less mediated than other media, say Television or PowerPoint presentations.

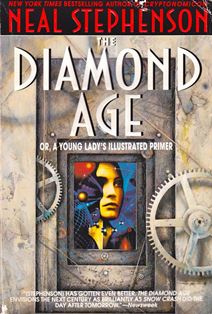

Second, there is the do-it-yourself ethos and the celebration of studied craft traditions that derives directly from the Arts and Crafts Movement of William Morris and his Kelmscott Press. This idea is described brilliantly in the life and work of bespoke artisans and master book artists in Neal Stephenson’s 1995 sci-fi novel, The Diamond Age (or a Young Lady’s Illustrated Primer).

Second, there is the do-it-yourself ethos and the celebration of studied craft traditions that derives directly from the Arts and Crafts Movement of William Morris and his Kelmscott Press. This idea is described brilliantly in the life and work of bespoke artisans and master book artists in Neal Stephenson’s 1995 sci-fi novel, The Diamond Age (or a Young Lady’s Illustrated Primer).

We’ve already, above, discussed the illustration of textual metadata in Rabbi Jacob Freedman’s unpublished Siddur Bays Yosef (Polychrome Historical Prayer Book). The efforts of the free-culture movement articulated by Lawrence Lessig and others concerning all manner of cultural work, provides some contemporary inspiration for reviving creativity and artistic mastery in works of Judaism. As a yeshivah student in Israel in the early 1990s, Varady was introduced to the grassroots campus outreach mission of Lights in Action. In the 2000s, Varady’s first-hand experience witnessing the benefit of radical Jewish pluralism in the grassroots intentional community, Jews in the Woods, convinced him of the value of sharing inspirations and knowledge throughout the Jewish community regardless of sectarian or denominational affiliation.

Open Source, Open Content, and Open Standards

In the 2000s, the potential of Torah databases and open-source licensed user-generated content projects was just beginning to be explored. Digitized liturgy began to appear online at sites like Mechon-mamre, Hebrew Wikisource and Daat.co.il, however, on the whole, these new digital editions were provided without attribution, and thus lacked the authority inherent in knowing the clear provenance of a textual witness. Inspired by Douglas Rushkoff’s call for an Open Source Judaism, Daniel Sieradski developed a haggadah he called the Open Source Haggadah (2005) and proceeded to work on a web application he called the Open Source Siddur. However, these two projects lacked a clear Open Content license or attribution information for contributed content. Development of Dan’s siddur project stalled in 2006. As with Dan’s siddur, a number of other online siddurim cropped up on sites providing digitized liturgical content in a small variety of popular nusḥaot.

Meanwhile, a graduate student at Harvard, Efraim Feinstein, was looking for an active Free and Open Source (FOSS) project for developing a siddur. A self-taught hacker, Feinstein found that the other existing projects were either technologically inadequate to the task, or insufficiently supportive of free culture values. While Varady’s “Open Siddur Project” proposed a similar idea, a six year old web page without a code base made him think that the author had gone on to other things and that the project was forgotten. Finding no active and worthwhile project to partner with, Efraim began on his own, calling it the Jewish Liturgy Project (JLP) because “all the obvious names were taken”.

Feinstein coded on and off, going through different versions of standard and non-standard methods of XML encoding, and finally settling on an encoding schema defined by the Text Encoding Initiative (TEI). Efraim began transcribing a haggadah over a period of two months, from January to March 2008. Not wanting to announce the project until he had produced something minimal to release, the project was not made public until the first code was committed to Google Code on December 10, 2008.

Later that month, on December 31, 2008, a young self-taught Brooklyn hacker named Azriel Fasten contacted both Feinstein and Varady, asking the latter about reviving the Open Siddur. Varady and Feinstein were soon introduced and agreed on a common vision for the project. Feinstein, who fully embraces the culture of free and open source software development, welcomed Varady’s willingness to contribute, and was happy to connect his project to that of the Open Siddur name. Varady was overjoyed that a passionate developer community was coalescing around this newly shared vision and was eager to help Feinstein lay the foundations for a robust server process, XML encoded digital text archive, and web application.

Public Launch and early years, 2009-2016

Aharon Varady submitted a proposal to attend the PresenTense Institute in Jerusalem’s summer workshop. His participation was supported through the Kaplan Family Foundation and a small grant from the Jewish Publication Society. The Open Siddur Project was publicly launched with the help of PresenTense Institute and an article in Ha’aretz by Raphael Ahren. A fiscal sponsorship through an established non-profit was arranged with Bob Goldfarb’s Center for Jewish Culture and Creativity (now, Jewish Creativity International). Aharon, Efraim, and a small community encouraged by the idea of Open Source in Judaism presented their vision at conferences and gatherings — at the Jewish New Media Festival, Limmud NY, Le Mood Montreal, NewCAJE, and the Minerva/EVA Conference on Digitization of Jewish Culture. Accounts on popular social networking sites were established to announce and discuss new developments. The project relied on Google’s free RSS feed service to deliver regular emails with digests of project development posted to the site.

While Aharon worked to develop the website, cultivate an online community, and solicit resources through philanthropic organizations, Efraim set work on developing the Open Siddur database, server, and client software. By 2012, it was clear that development of the software would take a number of years, and that funding would not be forthcoming without a working application to show to prospective funders. That year, the project website at opensiddur.org was transformed into an archive of liturgy and related work transcribed from the Public Domain and/or shared with Open Content licensing. Initially, development of the Open Siddur focused primarily on building core processes, standards, and text resources. By 2013-2014, much of the heavy lifting on this work was completed. Work on the client interface, began in earnest in 2014. While work on an Open Siddur application continues on and off at https://app.opensiddur.org, this development remains the singular pursuit of Efraim Feinstein.

Development of opensiddur.org, 2016-present

Beginning around 2016, with confidence ebbing in the usability of a functional web-application, Aharon increased his attention on transcribing and preparing liturgical resources, and soliciting resources from others. Len Fellman contributed his entire collection of tropified parshah and megillah translations and Isaac Gantwerk Mayer also began sharing prayers and readings, contemporary and historical. With site contributions from more contributors, Aharon was motivated to improve opensiddur.org, adding an increasing number of categories, author pages, author index, and more advanced search capabilities.