This work is in the Public Domain due to the lack of a second copyright renewal made by the copyright holder listed in the copyright notice before the expiration of the initial copyright renewal (a condition required for works published in the United States between January 1st 1924 and January 1st 1964).

This work was scanned by Aharon Varady for the Open Siddur Project from a volume held in the collection of the HUC Klau Library, Cincinnati, Ohio. (Thank you!) This work is cross-posted to the Internet Archive, as a repository for our transcription efforts.

Scanning this work (making digital images of each page) is the first step in a more comprehensive project of transcribing each prayer and associating it with its translation. You are invited to participate in this collaborative transcription effort!

[ACKNOWLEDGEMENT]

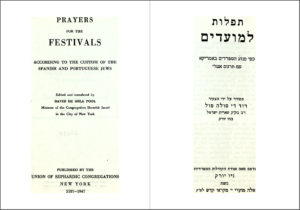

This Festival Prayerbook marks the completion of the publication by the Union of Sephardic Congregations of the liturgy according to the tradition of Sephardic Jewry. The publication of these books and their sale below cost have been made possible through the generosity of a number of friends. Initiated as a memorial to Lillian H. Hendricks, the Daily and Sabbath book is now in its third edition. The book of prayers for the New Year was made possible in the same way. A volume for the Day of Atonement, now in its second edition, was published in memory of Bertha Bueno de Mesquita. This festival volume is a tribute to the memory of Herman and Anna Salomon. The Union of Sephardic Congregations is deeply grateful to the generous friends who with faith and devotion have reared an enduring memorial to their dear ones.

To the Rev. Dr. David de Sola Pool, rabbi of the Congregation Shearith Israel in the City of New York, the Union of Sephardic Congregations wishes to record its special gratitude for undertaking the careful editing of the Hebrew text, its translation into English, and seeing the entire work through the press. These four volumes represent an undertaking extending over a period of twelve years. Following the example of his forebears, rabbis in Israel, and in their spirit, Dr. Pool has prepared this edition of our liturgy as a labor of love and reverence, that new generations may with deep devotion perceive and prize the beauty, comfort and inspiration of Israel’s time-honored prayers to the Almighty Father of all mankind.

INTRODUCTION

THE MESSAGE OF THE FESTIVALS

The characteristic name given by the Bible to the three great religious festivals in the Jewish year is mikra kodesh, a hallowed assembly. Passover, the Festival of Weeks, and the Festival of Booths (Tabernacles), together with its Eighth Day Closing Festival, are primarily occasions for calling together the Jewish people in consecrated gathering for rejoicing before God. In Biblical days these three seasons would witness in all parts of the Holy Land a great outpouring of people going up to the Temple in Jerusalem, there to celebrate the festival with sacrifice, prayer and rejoicing within the Temple precincts. To this day the prayers of these festivals retain many a reminiscence of those pilgrimages and their Temple ritual. These reminiscences bind us to the religious rejoicing of our ancestors in the Promised Land, the Land of Israel, two thousand and more years ago.

They lived close to the soil. For them these three festivals were occasions of thanksgiving for the blessings of life-giving food brought forth from the earth.

PESAH

With the spring festival of Passover came the beginnings of the barley harvest. Then the Omer (page 113), the first sheaf of barley, was ceremoniously offered to God. The winter rains were over, and the long drought of summer began. It was natural then for our ancestors to turn to God on the Passover with prayers for a season of copious dews so that verdure for men and cattle should not altogether wither and die. (The Prayer for Dew, page 302).

SHABUOTH

Seven weeks later, in the early summer, Shabuoth, “the Festival of Weeks”, came around, bringing with it the first-fruits and the later grain harvest. In keeping with the spirit of this festival of the first fruits, it is often customary to adorn the synagogue with the flowers of the field. We read the idyll of the Book of Ruth (page 352), its noble story of exquisite charm standing out vividly on the background of a barley harvest in Bethlehem three thousand years ago.

SUCCOTH

A little over four months later, in the month of Tishri, as the summer mellows into fall, there comes the Succoth period of the fruit and grape harvest. Then of old the harvesters and the watchmen built their simple harvest booths in the fields. It was then on the Succoth “festival of our rejoicing” that in religious rejoicing they waved the lulab cluster — the palm- branch, myrtle, willow of the brook and citron ( page 198). And it was then also when the final ingathering from the fields was completed, that the farmer and his household, his laborers, and the widow, the fatherless, the stranger, and the landless Levite, united in a jubilantly happy religious festival in gratitude for the blessings of the harvest. It was then, too, that our ancestors looked for the coming of the early “former rain” which would break the six months drought of the Palestine summer. These rains, with the “latter rain” of the winter, brought the promise of life itself to the land and its people. If the rain were scanty or were to fail, crops would fail, wells and streams would run dry, and stark want or even famine would loom for both man and beast. Therefore, together with the daily Succoth circuits around the altar in the Temple there went a devout prayer for rain. This came to its climax on the seventh day, Hoshaana Rabbah, “the Great (Prayer) ‘O Save Us’” through rain in its due season. Our circuits around the synagogue on each weekday of the Succoth festival with the prayers of the Hoshaanoth, especially on the seventh day, Hoshaana Rabbah {page 435 ), and the Prayer for Rain which characterizes the services of the eighth day (page 319), make vivid for us our sense of dependence on God for the blessings of life.

These spiritualized festival rejoicings for the bounties which God puts within reach of hands that will wisely work for them, come down to us from the dim ages before even the dawn of Israel’s existence as a nation. But with the birth of the Jewish people, these primal and universal festival aspects of mankind’s sublimated material existence took on added associations from the newly bourgeoning national life of Israel.

THE HISTORIC PASSOVER

Passover, the spring festival of the birth of life from the soil, became also the festival of the birth of the Jewish people. It was on the eve of the Passover, at the full moon of Nisan, at midnight, that the call came to Israel to rise up and go forth freed from the oppressing hand of Egypt. Since that night, Passover has ever been to the Jew, as it might well be to free men everywhere, “the festival of our liberation”. No year goes by but that Jews everywhere gather on the eve of Passover to retell the ancient story (Haggadah) how God redeemed Israel from Egyptian bondage and how freedom was born for all mankind (page 56). In the synagogue services, the Biblical selections play stirring variations on this immortal theme of human liberty.

SHABUOTH AND SINAI

The triumphant exodus from Egypt freed Israel from the physical taskmaster. But Israel’s soul, inured to generations of bondage, was not liberated until God’s revelation of the Torah at Mount Sinai seven weeks later, in the month of Sivan. With the giving of the Torah, the soul of man which had been groping in darkling ways became illumined with the light and guidance of ultimate truth. At Shabuoth, “the festival of the giving of our Torah,” the human soul was offered emancipation from servitude to superstition as well as from man’s injustice. Thus Shabuoth, which celebrated the harvesting of the first-fruits of the soil, became also the festival of the first-fruits of man’s spiritual garnering through the God-given Torah. The solemn proclamation of the Ten Commandments (page 252) is the heart of the Shabuoth service. At the afternoon services their elaboration is presented through the Azharoth (page 326), enumerating the 613 specific commandments found in the Torah of Moses.

SUCCOTH AND THE WILDERNESS

But neither the exodus from Egypt nor the revelation at Mount Sinai achieved complete freedom of body or spirit for the children of Israel. They needed the discipline of forty years of desert wandering before they were prepared to enter the Promised Land and live truly as freemen. During these forty years they wandered wearily, impatiently, rebelliously. Those were years of training for freedom. Succoth, occurring at the dangerously exuberant moment of the grape harvest, as a national festival sounds the call for inner discipline. Though most of us today do not dwell in harvest huts in the fields, we yet dwell in booths on Succoth, that our “generations may know that God made the children of Israel dwell in booths when He brought them out from the land of Egypt.”

Thus all the three festivals, Passover, the Festival of Weeks, and the Festival of Booths, come down to us enriched by the twofold message of soil and soul. They bid us look on the Land of Israel and on the nation of Israel in the light of eternity and with eyes of the spirit. When the Jew wends his way to the synagogue on those days to reunite himself with his brothers in hallowed assembly, he is dedicating himself anew to the noblest ideals of his people and of all mankind. He is reconsecrating himself to face life with the new courage and sense of high and chastened purpose with which his religion should inspire him. On these three festivals he is bidden appear before God, and not to appear empty of the gifts that he should bring in thanksgiving. But one must be indeed barren of soul who can appear before God and share in the time-hallowed prayers and teachings of these days and not also receive from them a rich reward of spiritual gifts.

SIMHATH TORAH

Closing the cycle of these three Biblical festivals comes Simhath Torah, “The Rejoicing of the Torah”. This gives special character to the second day of the Shemini Hag Atsereth closing festival. It is a celebration of later origin than the Biblical festivals, but one which springs from the deeps of the Jewish soul. It marks the turning point in the Jewish year of spiritual education. The closing chapters of the last book of the Torah of Moses are read to the Hatan Torah, “the Bridegroom of the Torah,” a reading that is followed immediately by the opening chapter of the Torah read to the Hatan Bereshith, “the Bridegroom of the Beginning”. This symbolizes the unending cycle of Jewish devotion to the Torah which is our life and our length of days:- “This book of the Torah shall not depart out of thy mouth, but thou shalt meditate therein day and night in order that thou observe to do as all that is written therein, for then shalt thou make thy way prosper, and then shalt thou do wisely.

Illumined in mind, in purpose and in soul by this rededication to the Torah, the source of Israel’s life, the children of Israel are strengthened by the prayers of these festivals to go forth chastened, uplifted, and the more worthy of bearing their historic mission to be God’s witnesses on earth.

May this venerable and time-hallowed book of Israel’s traditional religious rejoicings help bring to this generation the religious aspiration, strength, wisdom and upsurge of soul which come from God. May the liberty of Pesah, the commandments of Shabuoth, and the joyous discipline of Succoth deepen in us the sense of dependence on God and the rejoicing in Him which flow as a perennial stream of blessing from all the festivals of the Jew.

THE FESTIVAL SERVICES

EVENING SERVICE

The evening service of each festival opens with a Psalm associated with the special message of that day. On Passover, the celebration of redemption from slavery, Psalm 107, (page 19 ), sings of the thanksgiving which man should give to God for every escape from evil. On Shabuoth, the day of God’s revelation. Psalm 68, (page 22), paints a brilliant picture of a manifestation of God. On Succoth, the third of the pilgrim festivals, Psalms 42 and 43, (page 25), recall an exile’s yearning memories of the time when he marched in festive throng to the Temple, while on the Eighth Day Closing Festival the twelfth Psalm, (page 27), is chosen because its superscription assigns it for the Sheminith, “the Eighth”. The service then follows the usual order of the Sabbath evening service, adding the proclamation of the festival (page 34).

The heart of the Amidah emphasizes the religious obligation of the festival rejoicing. After the close of the Amidah, there is chanted a second Psalm characteristic of the day. On the Passover this is Psalm 114, “When Israel went forth from Egypt” (page 42). On the other festivals Psalm 122, (page 42), is sung as one of the pilgrim Psalms recalling the festal joy of the pilgrims as they thronged within the walls of the Holy City on the three pilgrim festivals.

The home ritual of the Passover eve is explained in the text (page 56).

MORNING SERVICE

The morning services closely follow the order of the weekly Sabbath morning service with the addition of the special Psalm of each day and the exultant Hallel psalms of rejoicing (page 199). This rejoicing is constrained by the omission of parts of these Hallel Psalms on Passover after the first two days, in sympathetic memory of the bereavement and sorrow which came to the Egyptian foe at the Red Sea. The selections from the Torah and the Haftaroth are clearly apposite to either the historical or the agricultural associations of the festival days. Specially notable are the Haftarah of the Sabbath in the intermediate days of the Passover with its promise of new life out of the dead past, (page 422), the last day of Passover with its vision of future glory, (page 248), and the second day of Shabuoth with the prophet’s rapt vision of the manifestation of God (page 258).

SPECIAL SERVICES

The seasonal Prayer for Dew recited on the first day of Passover (page 302) is made up of brief but brilliant poems by Solomon ibn Gabirol and other poets singing of the vivifying dews as a precious symbol of happiness, hope and life.

The distinguishing features of the Shabuoth ritual, which for the most part are associated with the afternoon services, are commented on above, while an explanatory introduction to the Azharoth is given on page 326.

The Hoshaanoth chanted on the seven days of Succoth (page 307), are built on a uniform literary pattern. Their main hymns are from the pen of Joseph ibn Abitur, a Spanish poet of the tenth century, who has worked his signature “Joseph” into a number of them. However, some attribute some of these poems to Joseph Kimhi of Spain (1105-1170).

Over the years there has grown up the thought that the judgment of the individual which had been declared on the Day of Atonement is finally sealed and put into effect twelve days later on Hoshaana Rabbah. This thought accounts for the numerous echoes of the Atonement Day service which are found in the special prayers of Hoshaana Rabbah.

The Prayer for Rain added in the Musaf of the Eighth Day Closing Festival, (page 319), follows the general pattern of the Prayer for Dew on Passover.

SIMHATH TORAH

Simhath Torah, which overlaps the second day of the Eighth Day Closing Festival, is also designated in the prayers as this Eighth Day. Sephardic rituals for Simhath Torah, the Rejoicing of the Law, differ much in detail according to local custom. While the Biblical readings to the Hatan Torah and Hatan Bereshith are everywhere the same, the songs sung in their honor and the processions and circuits with the Torah vary among Sephardim between a rich profusion in communities of Mediterranean tradition, and a comparative absence of them in communities of Dutch Sephardic background. This comprehensive volume has sought to do justice to all rites within the fundamental unity of Sephardic tradition.

May each worshipper find in these pages a new understanding of the deep inner joy which ever comforted our ancestors, and strengthened them to “worship the Lord with gladness, and come with exulting into His presence.”

“📖 תפלות למועדים (מנהג הספרדים) | Tefilot l’Mo’adim, arranged and translated by Rabbi David de Sola Pool (1947)” is shared through the Open Siddur Project with a Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication 1.0 Universal license.

Not that I am going to make a big deal of this – but why do you think that this book was not renewed?

see here: https://exhibits.stanford.edu/copyrightrenewals/catalog/R581583

Thank you Zachary for locating this renewal record. I can’t remember whether we found it in our initial copyright research or not; the name in the copyright notice (“de Sola Pool”) differs slightly from how it was recorded in the renewal record (“deSola Pool”) and that might have led to an oversight. Regardless however, this initial copyright renewal made in 1974 expired in 2003. The work is therefore now in the Public Domain. Were it not for the original publication being published before 1 January 1964, we might think that, according to the 1976 Copyright Act, the copyright should last for 70 years after Rabbi de Sola Pool’s death (70 + 1970 = 2040). And if that were the case, we would instead claim our Reproduction Right, granted to public collections (archives and libraries) for the reproduction of materials within the last twenty years of their copyright. One last thing which may was probably relevant until the expiration of the copyright in 2003. The second copyright renewal here was made posthumously (four years after the rabbi’s death) by members of his estate, and a complex issue arises in certain cases between copyright law pre-1976 and estate law owing to estate law being under the aegis of state rather than federal law, as explained in this article.