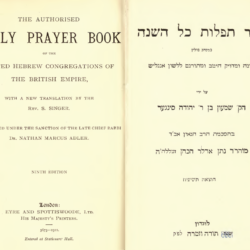

Selichot for the Propitiatory and Penitential Days, and for the Minor Fasts, to which are added the Selichot for the Minor Day of Atonement with a New English Translation by David Asher, Ph. Dr. (Vallentine & Sons 1912) is, we believe, the most comprehensive collection of seliḥot with an English translation in the Public Domain.

Scanning this work is the first step in a more comprehensive project of transcribing each prayer and associating it with its translation. You are invited to participate in this project!

This work was scanned by Aharon Varady for the Open Siddur Project from a volume held in the collection of the HUC Klau Library, Cincinnati, Ohio. (Thank you!) This work is cross-posted to the Internet Archive, as a repository for our transcription efforts.

The following preface was copied from the 1866 edition not found in later reprints. (Many thanks to Jeffrey Maynard for sharing page images of the Asher’s Preface from his blog, Jewish Miscellanies.)

PREFACE.

In offering this translation of the Selichoth, the first ever attempted in this country, to the Jewish public, a few prefatory words on the origin of these prayers, their character and authors, as well as on my version itself will be necessary. Thanks to the researches of the celebrated Zunz, who has all but exhausted this subject, my task is rendered sufficiently easy, for the result of his investigations is embodied in his learned work, “Die Synagogale Poesie des Mittel-alters” (“the Synagogue Poetry of the Middle Ages”), and, with the exception of a few additions, all that is left me to do is to abridge and translate his statements for the benefit of the English reader. This candid avowal on my part is no more than was due to the man who has laboured so long and so successfully in a field almost untrodden before him, and if my own merit is lessened by my not being able to lay any claim to original research, the value of what I have to bring forward will only be enhanced by its bearing the authority of so great a name.

The word Selicha we first meet with in the holy writings, viz. in the Psalms,[1] See Ps. 130:4. Nehemiah,[2] See Nehem. 9:17. and Daniel,[3] See Dan. 9:9. where, however, it only signifies the pardon granted by God. But as it is the sole object of these prayers to solicit such pardon, the earlier terms תפלה and עבודה soon gave way to that of סליחה or propitiatory prayers. These prayers consist of Scriptural verses, mostly, however, of mere fragments of verses: the words themselves being often applied in a different sense from that which they etymologically bear. Occasionally Rabbinical terms, taken from the Talmud and the Midrash, are interspersed, so that the composition may be likened to a kind of Mosaic work, the classical groundwork of the biblical Hebrew being inlaid with the Aramaic, Greek and Persian elements of the Rabbinical language.

The selicha (pardon) comes from God, who grants it on being entreated for it; the act of prayer is man’s duty. In the poetical pieces such prayers are therefore never mentioned by the term Selicha, but always by the ordinary expressions, such as עתירה ,תפלה, בקשה ,תחנון ,שועה, &c. It was, however, but natural, that the name of Selicha should subsequently be transferred to the prayers themselves.

The term פזמון (Pismon) is to be traced back to Augustin, who composed psalms with an introductory verse, which is repeated after every strophe. He termed this refrain Hypopsalma, and from this word, as may be seen by reference to the Targum of Job, where the Hebrew ענה (to recite) is rendered by פזם, the term פזמון has been derived.

The Selichoth are variously constructed of 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 9, 10 or 12 lined strophes, and are always in rhyme.

In the supplications (Techinoth) at the conclusion of each day’s service of Selichoth, the Israelites disclaim all merit of their own, and appeal solely to the love and mercy of God; sometimes their present[4] See p. 22. misery is contrasted with their former prosperity, and expressions of hope close the supplication. The powers and attributes of the Supreme Being, such as His love, the 13 Middoth (Attributes), even the Torah itself, are appealed to, to intercede for Israel; heaven, the throne of God, nature, angels, departed illustrious men, the forefathers are called upon to unite in prayer with their children. Job and Daniel speak of heavenly intercessors, and according to the Talmud it is permitted to solicit the intercession of the angels, though it is forbidden to address a prayer to them directly as saviours. Hence each day’s propitiatory service concludes with the prayer מכניסי,[5] Synhedrin 44. which is addressed to the angels appointed to convey prayers before the throne of God. This idea was nourished by the belief that the angels preside over nations and the powers of nature, and that each divine power, designated by some mysterious appellation, is represented by an angel, especially by the so-called Archangels, imagined to have a place in heaven, such as Michael, Metatron, and others. The imagination of the people had created hosts of good and evil spirits, more or less proximate to the Divinity, and the party divisions on earth were supposed to be emanations of the struggle between higher powers; such was the belief both of the ancient world, and of the middle ages. The Coptic, Abyssinian, Greek and Romish churches have appeals to angels, and in Christian prayers of the eighth century, eight angels, borrowed from the Jews, are invoked. Notwithstanding the strictness of Jewish monotheism, the belief in the protection and friendship of the angels was compatible with it; they wept over the offering up of Isaac, and over all the sufferings that befell his posterity; they praise the Lord in the sacred tongue; conduct the souls to the abodes of peace; convey the prayers of the congregations before God; and implore Him when He is angry, whereupon the fiery words proceed from His throne, “Blessed be ye, advocates of my children! Praised be ye for reminding me of the merit of their fathers!” Although, however, none of these prayers could lead the suppliant to believe that his salvation depended on any one but God Himself, the introduction into the prayers of the names of angels and the above-mentioned piece מכניסי met with much opposition ever since the close of the twelfth century, when, philosophy and mysticism having been widely disseminated, the spiritual powers and their personifications occupied, inflamed, and divided the minds of men. The so-called holy names had been made use of for amulets, and numerous superstitious writings teemed with them in the Geonic age. Maimonides and others censured this abuse; and equally so the petitions addressed to the angels were found fault with, among others by Nachmanides, who, in a public discourse, pronounced against the invocation of the Archangel Michael, and against the “Machnisse.” But notwithstanding the opposition of many other great authorities to these appeals to the angels, popular belief and routine prevailed over reason, and the Selicha commentator of 1568 advocated the retention of “Machnisse;” and declared the apprehensions of the opponents to be exaggerated. I may here add, that an ingenious explanation has been offered by others, which, if correct, ought to have obviated every controversy on the question. It is asserted that the “Machnisse” is addressed, not to the angels at all, but to the congregations joining with us in prayer, and there is at least nothing in the wording of the piece opposed to this assumption. Nay, it even finds some support in the Talmud,[6] i.e., the time at which the prayers were composed. where we read as follows: לעולם יבקש אדם רחמים שיהיו הכל מאמעציו את כחו.

“The petition of the individual will be strengthened by that of the collective body,” and Maimonides, too, corroborates this view, and will not allow of any mediation between man and his Maker. As to the character of the Selichoth in general there is a key-note running through them, which, similar to the melody in a song, amidst a variety of harmonies strikes the ear, and impresses the mind. In their totality they form a Rehitim-chain, composed of different, yet similar links: individually considered, the greatest differences, the richest variety presents itself. Both the diction and the contents vary according to time and place, origin and object of the prayer, but principally according to the peculiar manner of the authors. The earliest Selicha was the psalm, suited to all times; subsequently, groups of verses assumed the character of bouquets, held together by the propitiatory sentences twining around them.

As to the earliest author of these prayers, we scarcely know the name of one anterior to the age of Hai Geon (a. 1000), and of those who flourished at that period, at most three names can be mentioned, viz. Jose ben Jose, Saadia, and Meborach ben Nathan. About the middle of the 10th century the liturgy was enriched by men living in Greece, Italy, Provence, France, and Spain, and, a century later, these were followed by German Jews.

The authors supposed to have lived in Greece are, Salomo ben Jehuda, Shefatia, Benjamin ben Serach, Sebadia, Amitai, and Isaac Cohen. The French authors are: Gershom ben Jehuda, Simeon ben Isaac, Joseph Tobelem ben Samuel, Meir ben Isaac, (of Orleans), Salomo ben Isaac, (Rashi), Meir ben Samuel, perhaps also Isaac ben Moseh. In the Rhenish cities lived: Meir ben Isaac, David Halevi ben Samuel, David ben Meshullam, Menachem ben Machir of Katisbonne, Tobia ben Elieser, Meshullam, Mose ben Meshullam, Elieser Halevi ben Isaac, Benjamin ben Chiia, and Kalonymos ben Jehuda. In Rome: Shabtai ben Mose, Kalonymos ben Shabtai, (subsequently in Worms), Jechiel ben Abraham, Benjamin ben Abraham, Mose, Jehuda ben Menachem. Isaac ben Meir was a native of Narbonne. Of unknown origin are Isaac, Joseph, Elia ben Shemaja, Samuel Hacohen, Samuel ben Jehuda, Samuel ben Isaac, Benjamin ben פשדו. All these poets flourished in the 11th, and in the first half of the 12th century, contemporaneously with the great Spanish poets, who likewise cultivated liturgic composition. The earliest Selicha poet of the said period is Salomon ben Jehuda or Salomon הבבלי, who has been honoured with the epithet of Saint, and named by the side of Kalir, the great Piut-poet. But the most prolific Selicha poet of that century, and perhaps of all Romanic-Germanic poets in general, is, Benjamin ben Serach, who flourished about 1058; a man who, under other circumstances, would have become a champion for the liberties of his people. But his compositions were destined to be his only deeds; and for these the ancients conferred on him the epithet of the Great. His diction has mostly an easy flow, is often artless, and occasionally he neglects the rhyme. He is perhaps the first who composed independent Akedahs. Salomon ben Isaac, so well known by the cognomen of Rashi, (died 1105), was the author of eight Selichoth, sometimes more in biblical, sometimes more in rabbinical phraseology; most of them are written in a clear language, and only a few in the diction of the Piutim. Meir ben Isaac ben Samuel, the celebrated Reader of Worms, (about 1060), may be mentioned as the earliest of the sacred poets of the German Jews. His Selichoth abound in Talmudical quotations.

Several Selichoth might be assigned to their respective authors, but it being impossible to do so in every instance, I deem it useless to furnish what must seem a mere dry catalogue, and could certainly not claim a higher value. Before concluding these introductory remarks it will be necessary to remind the reader, that if there occur in these prayers many passages and expressions ill-suited to the present time, these objectionable passages date from the Crusades, when the Jews were subjected to the fiercest persecution, and every sentiment of pity seemed extinguished in the breasts of their adversaries.

And now a last word on the subject of my translation. Aware that the authorised version of the Bible has taken so firm a hold on the minds of the English public that no recent translation can be as yet supposed to have superseded it, I judged it best, wherever it was at all feasible, closely to follow the Anglican version, the language of which is as familiar to the English public as household words. In all other instances I have aimed at a like simplicity of diction, such as I humbly opine, is requisite for a prayer-book.[7] The translation of those Selichoth which occur also in the Jom Kippur service is taken from Vallentine’s edition of the Festival Prayers by the Rev. D. A. De Sola.

Finally, it is due to the German translator, M. Blogg of Hanover, to state, that I have often been guided by his rendering, and have largely availed myself of his notes.

May this first English translation of the Selichoth meet with a favourable reception on the part of my English speaking co-religionists in both hemispheres, so that the publisher’s exertions and sacrifices may not go unrewarded.

THE TRANSLATOR.

Leipzig, Sivan

5626. | 1866.

Notes

“סדר סליחות מכל השנה | Seder Seliḥot mikol ha-Shanah :: The Order of Seliḥot for the entire year, translated by David Asher, Ph.D. (1866)” is shared through the Open Siddur Project with a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International copyleft license.

Is work to transcribe this ongoing somewhere? Would like to contribute.

So far, it’s cross-posted here and in our collection of scanned (and digital native) works at the Internet Archive. We can get this posted to Hebrew Wikisource and start transcription there. Would you like to take the lead on this, Amir?