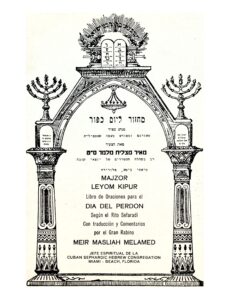

מַחֲזוֹר לְיוֹם כִּפּוּר Majzor leYom Kipur (Mexico: 1972) is the second edition of a bilingual Hebrew-Spanish nusaḥ Sefaradi Yom Kippur prayerbook compiled and translated by Rabbi Meir Matsliaḥ Melamed (1920-1989), first published in 1968. This “second edition” appears to be more of a “second printing” than an update or revision of the first edition. This Mexican printing was dedicated to “the Spanish speaking Hebrews of the city of Miami Florida, by Salomon and Esther E. Garazi in memory of Moises Egozi Flores” after their death in Miami on 9 July 1970. Rabbi Melamed had in 1971 been recently installed at the pulpit of the Cuban Sephardic Hebrew Congregation, after having served previously in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil where his 1966 Hebrew-Portuguese siddur Tefilat Masliaḥ was first published. For both prayerbooks, as no Hebrew type with vocalization and cantillation marks was available to Rabbi Melamed, liturgy was reproduced from images of older siddurim. Rabbi Melamed’s translation appears to the sides of these images and his commentary underneath.

This work is in the Public Domain as it was published in the United States within 30 days of having been published in a foreign country. Additionally, the work is in the Public Domain for not having been registered with the US Copyright Office, a required condition for works published before 1 January 1978.

Source (Spanish) Translation (English)

Miami, Abril de 1972.

Miami, April 1972.

Source (Spanish) Translation (English)

Source (Spanish) Translation (English)

VET = V

VET = V

CAF = C o K

CAF = C o K

“📖 מַחֲזוֹר לְיוֹם כִּפּוּר (מנהג הספרדים) | Majzor leYom Kipur (Libro de Oraciones para el Dia del Perdon), a bilingual Hebrew-Spanish maḥzor compiled and translated by Rabbi Meir Matsliaḥ Melamed (1968/1972)” is shared through the Open Siddur Project with a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International copyleft license.

Leave a Reply