This work is in the Public Domain due to the expiration of term of copyright for the copyright holder listed in the copyright notice (seventy-five years having passed since their death).

This work was scanned by Aharon Varady for the Open Siddur Project from volumes I and III held in the collection of the HUC Klau Library, Cincinnati, Ohio (thank you!) and volume II held in his private collection. All of these scans are cross-posted to the Internet Archive, the repository for our transcription efforts.

Scanning this work is the first step in a more comprehensive project of transcribing each prayer and associating it with its translation. You are invited to participate in this project!

PREFATORY NOTE

At the urgent request of several teachers, I have consented to issue this edition of the Authorised Prayer Book in parts. A comprehensive Preface explaining the plan of the work, and giving full acknowledgement of all help received, will appear on its completion.

I cannot, however, delay thanking the Jewish Religious Education Board for granting me the use of the Hebrew text; and Mr. and Mrs. Henry Freedman, of Leeds, whose idealism and wise-hearted generosity, in endowing this edition of the Prayer Book, will place it within the reach of all.

“It would be well for the Jewish religion if the beauty and devotional power so largely manifested in its prayers, were more intelligently appreciated by its adherents to-day”, said a well-known theologian not so long ago. The purpose of this work is to render possible such an intelligent appreciation on the part of the ordinary worshipper, and it is the fervent prayer of the author that, with the help of God, his labours lead to a deepening of devotion in the tents and sanctuaries of Israel in English-speaking lands.

Rosh Chodesh Cheshvan, 5702.

London, 21st Oct., 1941.J. H. H.

INTRODUCTION

I. THE JEWISH PRAYER BOOK

Its Paramount Importance

The Jewish Prayer Book, or the Siddur, is of paramount importance in the life of the Jewish people. To Israel’s faithful hosts in the past, as to its loyal sons and daughters of the present, the Siddur has been the Gate to communion with their Father in Heaven; and, at the same time, it has been the bond that united them to their scattered brethren the world over. No other book in the whole range of Jewish literature stretching over three millenia and more, comes so close to the life of the Jewish masses as does the Prayer Book. The Siddur is a daily companion, and the whole drama of earthly existence—its joys and sorrows; work-days, Sabbaths, historic and Solemn Festivals; birth, marriage and death—is sanctified by the formulae of devotion in that holy book. To millions of Jews, every word of it is familiar and loved; and its phrases and Responses, especially in the sacred melodies associated with them, can stir them to the deeps of their being. No other volume has penetrated every Jewish home as has the Siddur; or has exercised, and continues to exercise, so profound an influence on the life, character and outlook of the Jewish people, as well in the sphere of personal religion as of moral conduct.

For Understanding of the Jew

Surely the story and nature of such a book should be known not only to Jews, but to all who arc interested in the classics of Religion. Yet the Jewish Liturgy is the one branch of religious literature that is generally neglected by Christian scholars; and as to Jews of Western lands, but few of them can tell the origin, plan and message of their Book of Common Prayer. They know that the Shema and the Reading of the Torah constitute the central portions of the Synagogue Service, and arc also vaguely aware of some differences between Sephardi and Ashkenazi Jews as regards pronunciation and rendering of their Hebrew Prayers. For the rest, they do not know their bearings in the realm of Jewish Devotion, and move “in worlds not realized.” It is a most regrettable fact. For none can truly know the Jew—the Jew cannot know himself—without a clear grasp of the religious truths enshrined in his Prayer Book, or of the spiritual forces that were responsible for its rise and development.

And [For the Understanding] of Judaism

Just as indispensable is the study of the Siddur for the understanding of Judaism itself. It has been well said that its liturgy is the soul-index of a Religion. “You can tell from one’s prayers, whether he be a man of religious culture or a man of no spiritual breeding,” declares a Talmudic teacher. In the same manner, nothing reveals better the moral worth and message of a religious community, nothing is a truer confessional of its deepest thoughts and loftiest aspirations, than the historic prayers of that community. This is certainly so in regard to the Jewish Prayer Book. It is the liturgical expression of the hopes and convictions that had been accepted by the Jewish people as a whole. Furthermore, an investigation into the origins of the Siddur vindicates afresh, and from a new angle, the supreme place of Judaism among the religions of the world. It discloses the astounding fact that Israel, over and above its contribution of Monotheism and Prophetic ideals to the treasure-house of Humanity, has taught both true prayer and congregational worship to the children of men in producing the Psalms, the Synagogue, and the Jewish Liturgy— each of them a unique achievement in the annals of the Human Spirit. All this will become clear after a brief examination of the meaning of Prayer, the place of Prayer in Israel, the rise and significance of the Synagogue, and the history of the Jewish Liturgy.

II. PRAYER

Link Between God and Man

Prayer is a universal phenomenon in the soul-life of man. It is the soul’s reaction to the terrors and joys, the uncertainties and dreams of life. “The reason why we pray”, says William James, “is simply that we cannot help praying,” It is an instinct that springs eternally from man’s unquenchable faith in a living God, almighty and merciful, Who heareth prayer, and answereth those who call upon Him in truth; and it ranges from half-articulate petition for help in distress to highest adoration, from confession of sin to jubilant expression of joyful fellowship with God, from thanksgiving to the solemn resolve to do His will as if it were our will. Prayer is a Jacob’s ladder joining earth to heaven; and, as nothing else, wakens in the children of men the sense of kinship with their Father on High. It is “an ascent of the mind to God”; and, in ecstasies of devotion, man is raised above all earthly cares and fears. The Jewish Mystics compare the action of prayer upon the human spirit to that of the flame on the coal. As the flame clothes the black, sooty clod in a garment of fire, and releases the heat imprisoned therein, even so does prayer clothe a man in a garment of holiness, incandesce his whole being, release the light and fire implanted within him by his Maker, and unite the Lower and the Higher Worlds (Zohar).

Prayer in Israel

Prayer reaches its loftiest levels in our Sacred Scriptures. Every form of prayer is there found in perfect utterance, and in unsurpassed nobility and splendour. The Scriptural narrative is interspersed with prayer—individual prayers, as well as ritual prayers, such as the Priestly Blessing in Numbers 6:22. Organized prayer was sufficiently established by the time of Isaiah to have drifted into conventionality, and thereby aroused the indignation of the Prophet (chapter 1:15). However, no other people had the trust in God, or maintained it so unfalteringly from century to century, as had Israel amid all the tragic vicissitudes of its history: the darker the night, the brighter did Prayer shine in the soul of Israel. Israel’s motto might well have been Job’s “Though He slay me, yet will I trust in Him.”

Hebrew prayer shows no trace of magic and incantation, and is free from the vain repetitions in primitive and heathen cults. It is a true “outpouring of the soul”, a veritable cry “out of the depths” to our Father in Heaven. Prayer in Israel, furthermore, assumed new forms, alongside of adoration, petition, and thanksgiving. If in Greek the root-meaning of the verb “to pray” signifies “to wish”; and if in German it means “to beg”; in Hebrew, the principal word for prayer comes from the root, “to judge”, and the usual reflexive form (hithpallel) means literally, “to judge oneself.” The word tefillah, “prayer”, has therefore been understood as “self-examination”—whether we are worthy of addressing the Holy One, who demands righteousness and holiness of life from His worshippers. Thus, Job protests, “There is no violence in my hands, and my prayer is pure”; and one of the most popular synagogue Responses proclaims, “Prayer turns aside doom, but only if it is associated with repentance and charity.” Another explanation of the word tefillah is, “an invocation of God as judge,” an appeal for justice. Such was the prayer of Abraham when, pleading for the sinners of Sodom, he asked: “Shall not the Judge of all the earth do right?” And of this nature mostly are the prayers of the Prophets. “Thou art of purer eyes than to behold evil, and Thou canst not look on perverseness, wherefore lookest Thou upon them that deal treacherously, and boldest Thy peace when the wicked swalloweth up the man that is more righteous than he?” is the fearless question of Habakkuk.

Jewish prayer is as old as Israel. It is not generally known that, while prayer in Israel was an invariable accompaniment of sacrifice, prayer itself was quite independent of sacrifice. The significance of this latter fact cannot be overstated. Consider that even Plato speaks of prayer and sacrifice as inseparably linked together; and then go to the pages of Scripture, and you will find that Jacob prays for delivery from the hands of Esau, Moses intercedes for his People after the apostasy of the Golden Calf, Samson utters his agonized last petition, and the Prophet Jeremiah communes with God—all without sacrifice or the thought of sacrifice. Not that the place of sacrifice in the religious development of humanity is to be under-valued. But, as the Rabbis declare, prayer is greater than sacrifice; and pure spiritual prayer arose in Israel. Even a detractor of Judaism, like Julius Wellhausen, admits that “Israel is the creator of true prayer.”

The Psalms

The climax of the Hebrew genius for prayer is the Book of Psalms. Adoration can rise no higher than we find it in the five collections of ancient Hebrew hymns, known as the “Book of Praises,” Sefer Tehillim. It translates into simple speech the spiritual passion of the profound scholar; and it also gives utterance, with the beauty born of truth, to the humble longing and petition of the unlettered peasant. It early found its way into the Temple as part of the daily service; and to-day, after thousands of years, it is still the inspiration both of Jew and of Christian. In its words, believers have throughout the ages told God their woe, made confession of sin, asked for pardon and help, and rejoiced in the renewal of Divine favour. It is the hymn-book of Humanity.

The main data in regard to the Book of Psalms—its structure and teaching—will be given elsewhere. Here it is sufficient to remark that much of the discussion as to the authorship of the Book of Psalms has been singularly unhelpful. Negative dogmatism would deny any of the psalms to be older than the Babylonian Exile, and therefore could not be of Davidic origin. Yet a critical historian of the People of Israel acknowledges: “David is the most luminous figure and the most gifted personage in Israelitish history, surpassed in ethical greatness and general historical importance only by Moses, the Man of God. He is one of those phenomenal men such as Providence gives but once to a people, in whom a whole nation with its history reaches once for all its high-water mark” (Cornill). Furthermore, David’s noble lament over Saul and Jonathan—the most beautiful elegy in literature—proves him to have had the gift of true poesy; and immemorial tradition, as early as the days of Amos, regarded King David as the most eminent religious poet of his nation. And, besides, there was psalm-writing long before the days of David. Hymns, distantly akin to the Psalms, exist in Babylonian and Egyptian literature; and, in Israel, Moses sang his Song of Deliverance at the Red Sea, and Deborah her Ode of Triumph in the age of the Judges. There is thus no valid reason for doubting the essential truth of the tradition which declares David to have been the founder of the Psalter.

Equally liberating is the recognition that the supposed date or historical background behind a psalm, hardly affects the meaning of the psalm itself. Sometimes that historical background put forward by some moderns, as in the so-called Maccabcan psalms, is purely imaginary : thus, we find no allusion to enforced idolatry or to a faithless priesthood in those psalms which arc alleged to be the product of the Maccabean period. The fact is, that the sacred singers deal with the great simplicities of religion as reflected in the general experience of man; and, being lyrical poets in the highest sense, utter in the voice of one person a universal cry of the human soul. Humiliation for sin, thankfulness for mercies received, vows of constancy in spite of distress, burning faith that in the end it is well with the godly, submission to the will of God—all this is set forth in words expressive of similar emotions in every clime and nation. This is the reason why “the Psalter is the one body of religious poetry which has gone on, irrespective of time and place, race and language, speaking with a voice of power to the heart of men” (Ernest Rhys).

It is only necessary to add that the post-Biblical singers in Israel continued the work of the Psalmists. Like the Psalmists, they give voice to the sufferings of Israel, recall memories of the nation’s past, and are unwearied in their hopes of the mercy and justice of God. Theirs are the martyr-songs and penitential prayers (selichoth) which the Congregation of Israel chanted during fifteen hundred years of wandering and woe; while in the hymns (piyyutim) they expressed Israel’s unremitting cry for God throughout the ages.

III. THE SYNAGOGUE

But Judaism’s greatest contribution to humanity is in the domain of public worship, where alone man develops the wings and the capacity to soar into an invisible world. This it made through the synagogue. The synagogue represents something without precedent in antiquity; and its establishment, as we shall see, forms one of the most important landmarks in the history of Religion. It meant the introduction of a mode of public worship conducted in a manner hitherto quite unknown, but destined to become the mode of worship of civilized humanity.

Its Origin in Babylonian Exile

The origins of the synagogue, as of everything living and elemental, are shrouded in obscurity; and opinions differ widely in regard to the time and land of its birth. Some maintain that it existed in the days of the First Temple; others hold that it grew out of the lay devotional services which accompanied the daily sacrifices in the rebuilt Temple after the Exile; still others, that it is a product of Hellenistic Judaism, i.e. of the Jewries in Greek-speaking lands. Most scholars, however, arc of opinion that the synagogue and the beginnings of regularly recurring congregational Services first arose in the Babylonian Exile (597—538). During those fateful years in Israel’s life, something happened that had never before happened in history. Nations do not survive dispersion; yet a fragment of a small conquered people, forcibly transported to a distant land, remains there for a lifetime and docs not disintegrate. After two generations, it not only returns unimpaired to its own land, but does so with its national identity heightened, and its religious life immeasurably strengthened—a reborn Israel.

How was this miraculous transformation brought about? It is not impossible to reconstruct the situation, though no contemporary account of it has come down to us. After the final catastrophe in 586 B.C.E., the exiles—torn from home, and weeping by the rivers of Babylon over their subjugated land, their destroyed City, their burnt Temple—must have been dumbfounded by the unutterable calamity that had overtaken them. “God hath forgotten us; Israel’s story is at an end; we are a valley of dry bones,” they repeated. But they were accompanied by Prophets of Judah and Jerusalem who shared their sufferings. We are near to certainty, if we assume that Ezekiel, for example, would gather his brethren around him on Sabbaths and Festivals; and that, by Scripture reading and exposition, and llie singing of psalms they had heard in the now ruined Temple, he would fan the sparks of hope amid the ashes of their despair. They would listen with a new understanding to the Sacred Words read and spoken to them, and contritely repent the sins that had wrought the undoing of Israel. They would passionately proclaim both their utter rejection of idolatry and their devotion to the Holy God Whom they would henceforth serve with all their heart, all their soul, and all their might. Thereupon, the very Prophet who had foretold the fall of Jerusalem—and they had seen his prophecy fulfilled—would announce the salvation of a purified Zion, and proclaim the sure return of her repentant children to the land of their fathers.

The Prophet’s group of followers thus became a body of worshippers. The proved value of these Sabbath and Festival gatherings in reawakening the national and religious consciousness, would lead to the spread of the custom among other groups of uprooted Judeans. And the regular recurrence of these devotional occasions would, on the one hand, of necessity give rise to some scheme of prayer—outlines of theme, form and expression—to be used at such gatherings; and, on the other hand, lead to resurrection in the Valley of Dead Bones! James Darmesteter, the renowned Orientalist, relates that, when in India, he met a rabbi from Jerusalem who told him that, in the course of his wanderings through Persia, he had found a village entirely peopled with Jews descended from the bones resuscitated by Ezekiel. Little did he realize, remarks Darmesteter, that he himself, the wandering Jerusalem rabbi, was one of these descendants; and that all Israel are the children of the corpses revived by the religious activity of the Prophets during the Babylonian Exile.

Its Spread to Palestine and the Diaspora

Now, the memory of these religious assemblies was not forgotten when the exiles returned to the Homeland. Indeed, we find that within a century after Ezra, pious Jews throughout Palestine would meet on Sabbaths for the purpose of Scripture instruction, followed by religious devotion, and they would do so in a definite place set aside for that purpose. A century thereafter, in the year 247 B.C.E., we have the earliest contemporary non-Jewish mention of a synagogue building in the suburbs of Alexandria. The Hebrew and the Greek names for such “places of assembly” have remained the same to this day; they are beth ha-kenesseth and synagogue. By the time the Second Temple fell at the hands of Titus, in the year 70, there seems to have been a synagogue throughout the Roman world wherever Jews dwelt. In Jerusalem, they arc said to have been 480 in number; and ruins of beautiful ancient synagogues in Galilee have survived to this day. So fundamental had the institution become to the religious life, that the Rabbis, Philo, and Josephus, looked upon it as going back to a hoary past. However, as it docs not seem to have arisen before the Exile, there are no references to the synagogue in the pre-Exilic parts of Scripture, and but few in the later portions. It is generally agreed that in Psalm 74:8 (“they have burned up all the mo-adey El in the land”) there is such a reference. The literal meaning of the words mo-adey El is, “places of assembly,” and the Midrash and the ancient Versions translate them by “synagogues.” At any rate, it is ominous that the only Biblical mention of the synagogue should refer to its burning. That connection has, alas, remained typical in Jewish history. Every attempt to annihilate the Jew has included the wholesale destruction of his places of worship. One need but recall the ghastly aftermath of the Black Death in 1349); the 400 synagogues burned in Nazi Germany on November 10th, 1938: and the destruction of the Jewish houses of worship throughout France, that culminated in the bombing of six Paris synagogues on October 2nd, 1941.

Its Service Spiritual and Democratic

The new mode of worship inaugurated by the synagogue was democratic. The men who from the very first read and expounded the Torah and other Scriptural lessons, or led the worshippers in prayer, were rarely drawn from the priestly class. Anyone who possessed sufficient knowledge, and commanded the respect of his fellows, might do so. And that worship was spiritual. Sacrifices could not, of course, be offered anywhere outside the Temple. The Sacred Word, and not any sacramental or ritual act, was now the centre of worship; and that Sacred Word was the seat of religious authority and the source of religious instruction. Here we have something new under the sun. “With the synagogue there began a new type of worship in the history of humanity,” says a noted non-Jewish scholar, “the type of congregational worship without priest or ritual, still maintained substantially in its ancient form in the modern Synagogue; and still to be traced in the forms of Christian worship, though overlaid and distorted by many non-Jewish elements. In all their long history, the Jewish people have done scarcely anything more wonderful than to create the synagogue. No human institution has a longer continuous history, and none has done more for the uplifting of the human race” (R. T. Herford).

Copied by Christianity and Islam

After the Maccabean period the synagogue gradually eclipsed the Temple as a dynamic religious force, and spread with the Jew all over the world. Its service of prayer and religious instruction was taken over by both Christendom and Islam; the Church, in addition, embodying Song—the Psalms—in its worship. The language and formulae of the early Christian devotions follow Jewish models, and the forms and phrases of the Synagogue liturgy reappear in the most sacred prayers of the Church.

Its Place in Judaism

In Judaism itself, the synagogue proved of incalculable importance. Through it, the Sabbath and the Festivals penetrated more deeply into the Jewish soul, and the Torah became the common property of the entire people. Because of it, the cessation of the sacrificial cult, which cessation would in any other ancient religion have meant the end of that religion, was not in Judaism an overwhelming disaster. The reason is clear. Long before the fall of the Second Temple the synagogue had become the real pivot of Jewish religious life, especially so among the Jews outside of Palestine. The synagogue became the “home” of the Jew: a Midrashic teacher applies the words (Psalm 90:1) “Lord, thou hast been our dwelling-place in all generations”, to the synagogue. With the centuries, its scope broadened; and—together with the beth ha-midrash, the house of learning, attached to it—functioned also socially, as a school, religious court-house, public hall, and even as a hostel. Since the Middle Ages, the synagogue has been the visible expression of Judaism; it has kept the Jew in life, and enabled him to survive to the present day. With a truer application than that made by Macaulay in his day, we may declare that the Synagogue, like the Ark in Genesis, carried the Jew through the deluges of history, and that within it are the seeds of a nobler and holier human life, of a better and higher civilization.

IV. THE LITURGY

The Men of the Great Assembly

We must now consider the prayers that were spoken in the synagogue. These are ascribed to the Men of the Great Assembly—the Prophets, Sages, Scribes and Teachers who, in the centuries after the return from Babylon, continued the work of spiritual regeneration begun by Ezra and his fellow-leaders in the Restoration. They laid down the lines on which all Jewish congregational and individual prayer has moved ever since. They made the ברכה, the Blessing or Benediction, the unit of Jewish prayer: each Blessing beginning with the six Hebrew words for, “Blessed art Thou, O Lord our God, King of the Universe.” God is thus addressed in direct speech, “face to face”; and He is conceived not as a local or tribal deity, but as “King of the universe” (or, “of eternity”).

Lay the Foundation of Service

The Shema had long before their day come to be looked upon as the corner-stone of Judaism and Israel’s confession of Faith. To the Shema, the Men of the Great Assembly added the daily Litany of prayers, known as the Eighteen Benedictions. In it, the voice of Judaism speaks with the accent of the Prophets and Psalmists. In simple form, it unites praise and gratitude to God with spiritual longings and personal petitions.

The Men of the Great Assembly also introduced worship into the home, by instituting the Kiddush and the Havdolah for the incoming and outgoing of Sabbath and Festivals—the Kiddush re-affirming God as Creator, Deliverer and Lawgiver; and the Havdolah stressing the everlasting distinction between holy and unholy, light and darkness, which it is the mission of Israel to proclaim. In the scheme of the Rabbis, prayer covered the whole existence of the Jew. It was offered at the beginning and end of every meal, and every activity and human experience were hallowed by the thought of God. And they made devotion part of the very life of the people bv ordaining it as the daily duty of the Jew; because they knew—as an Anglo-Jcwish student of our Liturgy well put it—“that what can be done at any time and in any manner, is apt to be done in no time and in no manner” (Abrahams). This linking of the earthly with the Heavenly by means of a consecrated morning hour, this uplifting of everyday existence through communion with the Divine in prayer, has indeed proved an agency of immeasurable worth in the life of the spirit—as Jewish and Christian devotion throughout 2,000 years amply testifies (Elbogen).

Congregational Prayer

Two things of lasting influence must be noted in regard to this activity of the Men of the Great Assembly. The first is, they conceived the Service as primarily congregational; i.e. the worshipper prays not as an individual, but as a member of a Brotherhood; and his petitions arc couched in the plural, so as to include the needs of his neighbour. “In the synagogue there was no room for egoistic prayers; and, even in the prayers for the congregation, requests for material good were subordinated to petitions for the enlightening of the spirit and for moral power” (Perles). The most impassioned prayers in the Service are those which express the Israelite’s yearning for mankind’s recognition of God’s sovereignty, and for the final victory of righteousness in the universe.

Judaism attaches great importance to congregational prayer. Aside from the fact that public prayer is the strongest agency for maintaining the religious consciousness of a community, such prayer creates, maintains and intensifies devotion: the congregation, united in the proclamation of the unity and holiness of God, has the ardent conviction that its prayers will be answered. “Wherever ten persons pray”, says Rabbi Yitzchak, “the Shechinah, the Divine Presence, dwells among them.”

In Hebrew

And the second matter concerns the language in which Jewish congregational worship is held. Although the speech of the masses in Palestine at that time was Aramaic, the prayers of the synagogue were formulated in classical Hebrew; the vernacular, however, not being excluded; e.g. the Kaddish, then purely a prayer for the speedy coming of the Kingdom of God, remained in Aramaic. The Hebrew language had withdrawn from secular life, and was looked upon as leshon ha-kodesh, the Holy Tongue. Apart from the sense of mystery in the Service by the use of the Holy Tongue, increasing both the solemnity and emotional appeal of the Service, the Men of the Great Assembly rightly felt that the Synagogue Service must be essentially the expression of Universal Israel; and therefore, must be in Israel’s historic language, which is the depository of the soul-life of Israel. Hellenistic Jewry did not share this view, and it dispensed with the Sacred Language in its religious life. In its synagogues, the Torah was read in translation, and the prayers were in Greek. “The result was death. It withered away, and ended in total apostasy from Judaism” (Schechter). And those who in our own day seek the virtual elimination of Hebrew from our Services, aim, consciously or unconsciously, at the destruction of the strongest link both with our wonderful past and with our brethren in the present and future.

V. HISTORY OF THE LITURGY

It is not the purpose of this introduction to follow the story of the Liturgy in its development across the ages, and take note of its additions, modifications and ramifications in succeeding centuries. Many of them will be dealt with in the commentary on the different portions of the Service. The student who desires a comprehensive survey must consult the standard Jewish books of reference; and, for deeper study, go to the pioneering works of Leopold Zunz (1704—1886), the founder of the New Jewish Learning, or the illuminating book of Ismar Elbogen.

After the Destruction

Only the most outstanding facts in the history of the Prayer Book will here be mentioned. In the generation after the Destruction of the Temple by the Romans, the Synagogue Service was in essentials identical with the Service as we have it to-day. The principal prayer had long been the Shema. Its reading was now understood to be “the taking upon oneself the yoke of the Kingdom of Heaven”; i.e. the obligation of absolute and loving obedience to the Torah. And the Shema was preceded by two Benedictions—one in praise of the Creator of light, and the other as the Giver of the Torah; and it was followed by the Redemption prayer. The Eighteen Benedictions that had hitherto been largely in a fluid state—save as to their number, and the concluding formula of each Benediction—had their wording officially fixed. Also, a nineteenth Benediction was added, in order to purge the congregations of sectaries and apostates. The Eighteen Benedictions (the Amidah) had become part of all Morning, Afternoon, and Evening Services. The Responses (“Amen”, “Blessed be He and blessed be His Name”), and Doxologies (lit. “glory-words”, like “Blessed be the Lord, the God of Israel, from everlasting to everlasting”) had been taken over by the people from the Temple worship; so were the Psalms, recited by the pious as an introduction to their morning devotions; besides the Hallel (Psalms 113—118) which distinguished the joyful Festivals, New Moon and Ḥanukkah. On Mondays and Thursdays, there was a short Reading of the Torah; and on Sabbaths. Festivals and Fasts, also a Lesson from the Prophets.

Statutory Prayer

The prayers had become statutory, and were no longer spontaneous outbursts of devotion. But be it remembered that only divinely-favoured individuals arc capable of spontaneous prayer; the overwhelming majority of mankind must have their prayers—if these are to serve a spiritual and ethical purpose—written or spoken for them in fixed, authoritative forms. Statutory prayers, moreover, have their real, lasting and irreplaceable value. Heiler, the greatest authority on the psychology and history of Prayer, writes: “Formularies of prayer can kindle, strengthen and purify the religious life. Even in prayers recited without complete understanding, the worshipper is conscious that he has to do with something holy; that the words which he uses bring him into relation with God. In spite of all externalism, prescribed prayer has acted at all times as a mighty lever in the spiritual life.” Furthermore, fixed prayer alone prevented chaos at the individual centres of worship, and rendered possible uniformity in the Service of the various groups—something of vital importance in Jewry, with its children scattered to the four winds of heaven. At the same time, private prayer and the free effusion of the heart were duly esteemed; and a special section of the Service, the “Supplications,” was set apart for that purpose.

The regulations concerning the minutiae of prayer are many : the opening treatise of the Talmud, Berachoth, is entirely devoted to that subject. Schürer and other Christian theologians contend that these regulations must have stifled the spirit of prayer. But this is a controversial fiction. Rule and discipline in worship rather increase devotion: without them, the noblest forms of adoration are unknown. The same is seen in the kindred realm of poetry. Elaborate schemes of metre and rhyme—witness the Greek poets, or Shelley, Goethe, Hugo—alone seem to render the highest poetry possible. None realized better than the Rabbis the need for prayer to be true “service of the heart.” He who prays must remember before Whom he stands, they said; and it was neither the length, nor the brevity, nor the language of the prayer that mattered, but the sincerity. “The All-merciful demands the heart,” is their teaching. Even two brief individual prayers of that period illustrate that the fountain of devotional inspiration had not become dry. Rabbi Eliezer used to pray, “Let Thy will be done in Heaven above; grant tranquillity of spirit to those that reverence Thee below; and do that which is good in Thy sight. Blessed are Thou, who hearest prayer.” Rabbi Chiya’s prayer was, “Keep us far from what Thou hatest; bring us near to what Thou lovest; and deal mercifully with us for Thy Name’s sake Legal ordinances and casuistical discussions on prayer did not grow less with the centuries—only to stimulate the rise of the synagogal poesy, the wonderful hymnology of an Ibn Gabirol and Yehudah Hallevi, the burning fervour of the Jewish Mystics, and the naiveté and originality of the Chassidim, both in their Hebrew prayers and those in their vernacular. One of these vernacular prayers is, “Master of the Universe, I desire neither Thy paradise nor Thy bliss in the world to come; I desire Thee and Thee alone.” Such words are clearly in line with the rapturous cry of the sacred singer: “Whom have I in heaven but Thee? And there is none upon earth that I desire beside Thee” (Psalm 73:25). Spiritual religion has never found expression more living than in these utterances of Psalmist and Chassid.

But to return to the history of the Liturgy. The Talmudic age (200-500) added several prayers of genius to the Liturgy, notably those of the great Babylonian teacher, Rabh (175-247). The Gaonim, the heads of the later Babylonian academics (600-1040), sanctioned various enlargements of the Service; and, in the ninth century, produced the first collection of the entire Prayer Book, the Siddur of Amram Gaon. In the twelfth century, Moses Maimonidcs left a similar authoritative collection of the Prayers of the Jewish Year.

Sephardim and Ashkenazim

In the course of time, there arose two main streams of liturgical tradition: the Babylonian, which was transmitted to Spain, became the Sephardi Rite; and the Palestinian, which spread over Northern Europe, and is the Ashkenazi Rite. This latter has a Western branch, the German minhag proper; and an Eastern branch, the minhag of the Jews of Poland. The Polish minhag of the Ashkenazi Rite is now dominant in English-speaking lands.

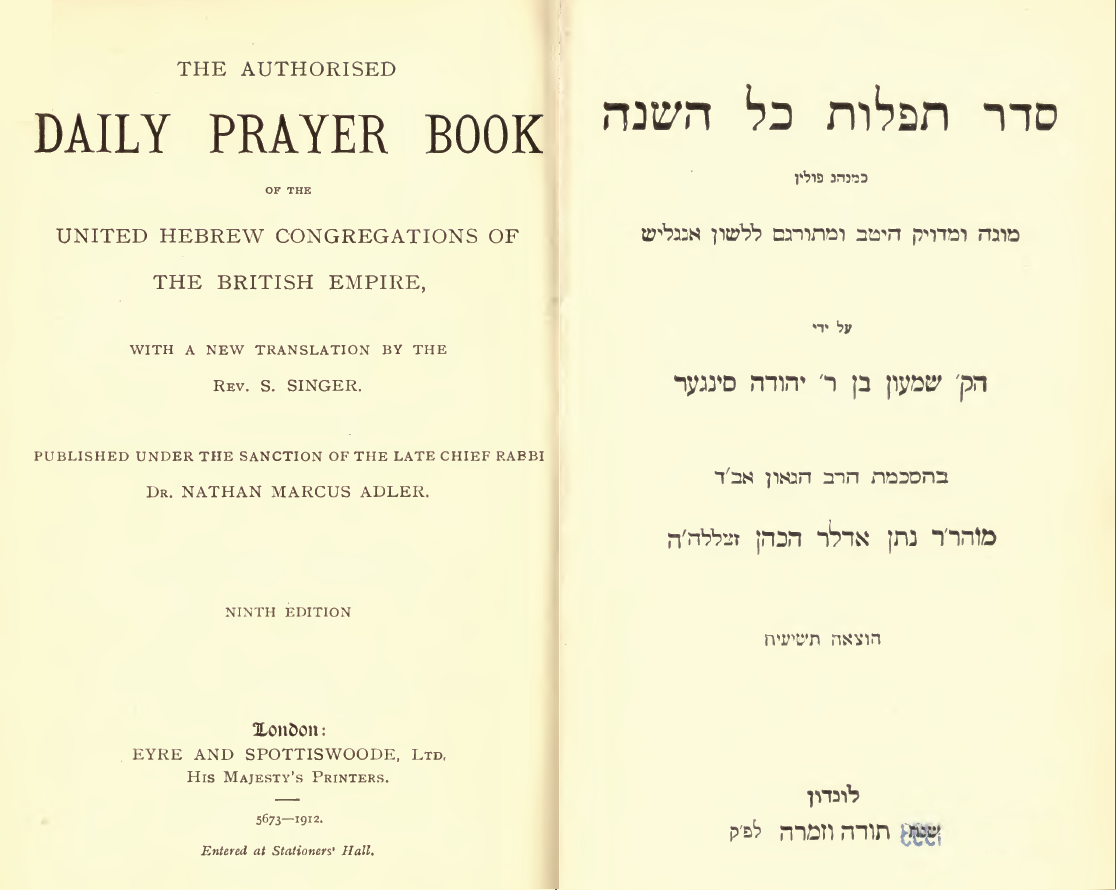

It is is quite beyond the scope of this commentary to deal with tributary or independent Rites of smaller Jewries—such as, the Italian, Byzantine, North African, Yemenite—or with local Rites, like those of Avignon, Corfu or Tripoli. In all Rites, the foundation prayers are practically the same; the divergences being mainly in regard to the voluntary “Supplications” in the daily Service, the piyyutim for Festivals, the selichoth on Penitential days, and the kinnoth on the Fast of Av. The first printed Prayer Book was the Ashkenazi Siddur in 1490. Scholarly editions of this Siddur are those of W. Heidenheiin in 1800, and of S. Baer in 1868. The latter was the basis of S. Singer’s Prayer Book, which first, appeared in 1890 under the sanction of Chief Rabbi Nathan Adler. It has been repeatedly reprinted, and is embodied, with revised translation, in this edition of the Authorised Prayer Book of the United Hebrew Congregations of the British Empire.

The Jewish Prayer Book

The Jewish Prayer Book is thus not the work of one man, one body, or one age. It is the gradual growth of many centuries—“like an old cathedral in all styles of architecture, a heterogeneous blend of historical strata of all periods, in which gems of poetry and pathos and spiritual fervour glitter, and pitiful records of ancient persecution lie petrified” (Zangwill). There is, of course, nothing religiously new in the Siddur; its phrases and teachings alike are either culled from Scripture and the Rabbinic Writings, or are a devotional paraphrase of them. This but makes it the truer an expression of the Jewish spirit, and but heightens its effectiveness as a summary of the Jewish Faith: the fundamental religious institutions, the basic doctrines of Judaism, as well as its millennial hopes, are ever afresh brought home to the conscience of the Jew in his daily, Sabbath and Festival worship. Only in the Psalter can we parallel the invincible faith, the resolute and unfaltering trust in God, the ardent desire to understand and obey God’s declared will, that we find in the Siddur. “When we come to view the half-dozen or so great Liturgies of the world purely as religious documents, and to weigh their values as devotional classics, the incomparable superiority of the Jewish convincingly appears. The Jewish Liturgy occupies its pages with the One Eternal Lord; holds ever true, confident, and direct speech with Him; exhausts the resources of language in songs of praise, in utterances of loving gratitude, in rejoicing at His nearness, in natural outpourings of grief for sin; never so much as a dream of intercessors or of hidings from His blessed punishments; and, withal, such a sweet sense of the divine accessibility every moment to each sinful, suffering child of earth. Certainly the Jew has cause to thank God, and the fathers before him, for the noblest Liturgy the annals of faith can show” (G.E. Biddle in Jewish Quarterly Review, 1907).

“📖 סדר תפלות כל השנה (אשכנז) | Seder Tefilot Kol haShanah :: the Authorised Daily Prayer Book of the United Hebrew Congregations of the British Empire, revised edition with commentary by Rabbi Joseph Herman Hertz (1942-1945)” is shared through the Open Siddur Project with a Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication 1.0 Universal license.

![Prayer of Intercession [for Britain in the War against Nazi Germany], by Rabbi Joseph H. Hertz (Office of the Chief Rabbi of the British Empire 1940)](https://opensiddur.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/prayer-of-intercession-office-of-the-chief-rabbi-1940-cropped.png)

Leave a Reply