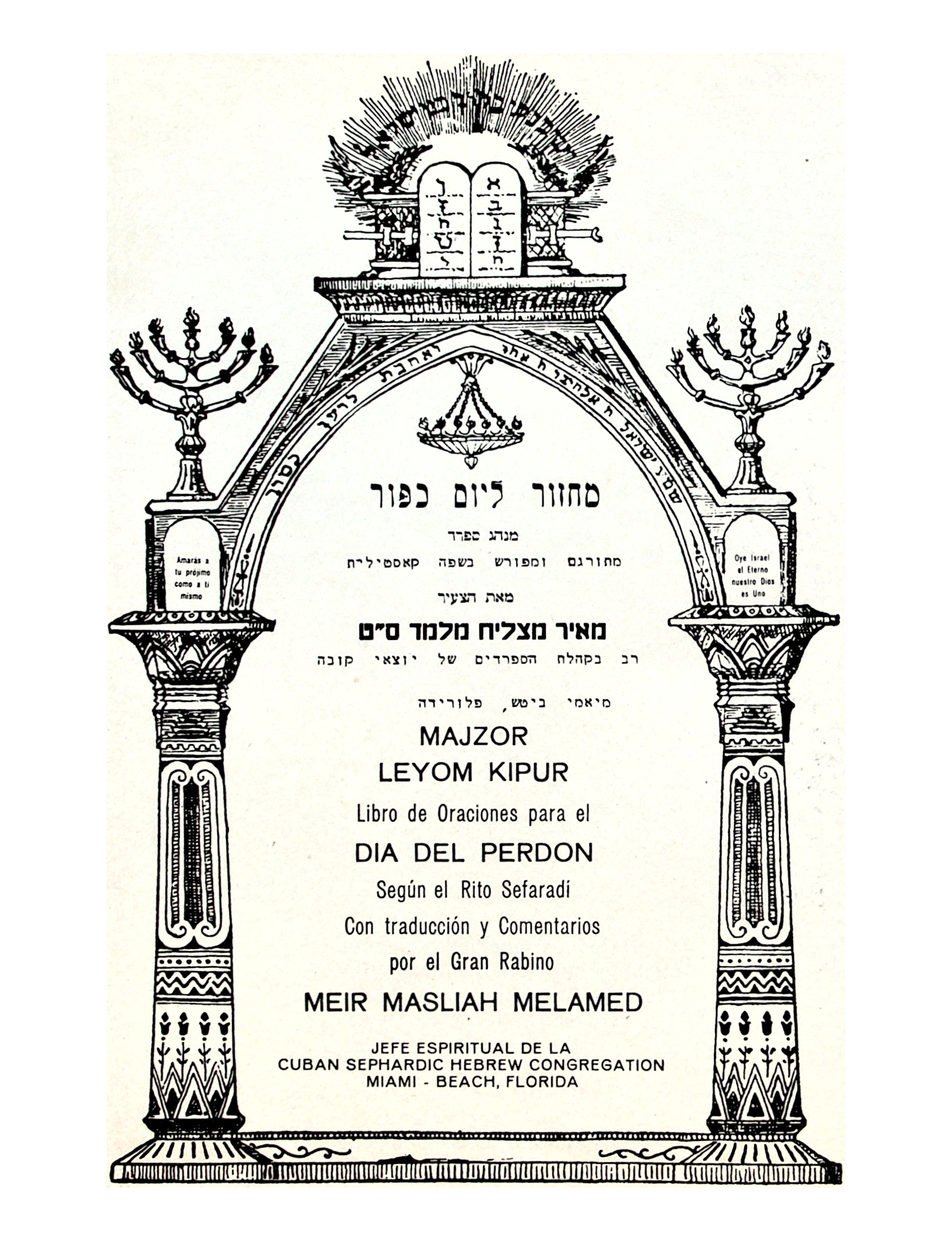

This is the first edition of סִדּוּר תְּפִלַּת מַצְלִיחַ Sidur Tefillat Masliah (Libro de Oraciones) (1974), a bilingual Hebrew-Spanish nusaḥ Sefaradi prayerbook compiled and translated by Rabbi Meir Matsliaḥ Melamed (1920-1989). As no Hebrew type with vocalization and cantillation marks was available to printers in Brazil, where Rabbi Matsliaḥ first began compiling prayerbooks, he developed a process of reproducing the liturgy from images of older siddurim and, occasionally, typewritten text. Rabbi Melamed’s translation appears to the sides of these images and his commentary underneath. This Spanish edition was preceded by a bilingual Hebrew-Portuguese edition published in Brazil in 1966.

This work is in the Public Domain due to its publication not having been registered with the United States Library of Congress, a condition required during the period in which it was published.

This work was scanned by Aharon Varady for the Open Siddur Project from a volume held in the collection of the HUC-JIR Klau library, Cincinnati. (Thank you!) This work is cross-posted to the Internet Archive, as a repository for our transcription efforts.

Scanning this work (making digital images of each page) is the first step in a more comprehensive project of transcribing each prayer and associating it with its translation. You are invited to participate in this collaborative transcription effort!

Source (Spanish) Translation (English)

Miami Beach, Enero de 1974

Miami Beach, January 1974

Source (Spanish) Translation (English)

R. — La Ley (Halajá lemaasé) es no repetir la bendición cuando se tiene la intención de volver a ponerlo (ver Sidur Bet Oved y Turé Zahav).

A. – The Law (Halacha lemaaseh) is not to repeat the blessing when intending to put it back (see Siddur Bet Oved and Turé Zahav).

R. — La mitzvá (precepto) de “Tefilín” tiene la prioridad sobre la del “Talet” pues la ley, para quíen solo puede comprar una sola cosa, talet o tefilín, es comprar los “tefilíin”; pero poseyendo los dos, se viste primero el “talet”, por que en él están simbolizados todos los preceptos de la Torá, incluso el de los tefilín según está escrito: “Y lo veréis y recordaréis todos los mandamientos del Eterno” (Num. XV, 39).

(Ver las leyes detalladas del “talet” y de los “tefilin” en este Sidur.)

A. – The mitzvah (precept) of “Tefillin” has the priority over that of the “Talet” because the law, for one who can only buy one thing, talet or tefillin, is to buy the “tefillin”; but possessing both, the ‘talet’ is worn first, for in it are symbolized all the precepts of the Torah, including that of the tefillin as it is written, “And you shall see it and remember all the commandments of the Eternal” (Num. XV, 39).

(See the detailed laws of “talit” and “tefillin” in this Siddur).

“Un huevo puesto por la gallina durante el sábado no se puede comer hasta la noche”.

R. — Imaginémosnos la opinión de los legos que leen semejantes leyes ¡R. Abraham Shalem no explica lo principal o sea el motivo de estas leyes porque él mismo lo desconoce. En la forma que él escribe no hay lógica alguna y solo puede causar impresiones negativas acerca de nuestra religión, lo que contribuye a alejar a los fieles de ella.

Los rabinos sicólogos no traducen textualmente todo lo que leen, siguiendo esta

recomendación escrita en los “Pirke Avot”: Jajamim izaharú bedivrejem! (Sabios! tengan cuidado en lo que dicen, para no causar interpretaciones erróneas¿)

“An egg laid by the hen during the Sabbath may not be eaten until evening.”

A. – Let us imagine the opinion of the laymen who read such R. laws. Abraham Shalem does not explain the main thing, that is, the reason for these laws, because he himself does not know it. In the way he writes there is no logic whatsoever and can only cause negative impressions about our religion, which contributes to alienate the faithful from it.

The rabbinic psychologists do not translate textually everything they read, following this

recommendation written in the “Pirke Avot”: Chachamim izaharu bedivrechem! (Sages! be careful in what you say, so as not to cause erroneous interpretations¿).

En el párrafo siguiente, R.A. Shalem también indica que “no se permite demorar o postergar el entierro para el día siguiente (o sea para el 2° día de fiesta), con tal de hacer todo el servicio por mano de Israel”.

R. —¡Por amor de Dios, no se guíen por estas indicaciones a no ser en casos extraordinariamente excepcionales y solo después de consultar con un auténtico rabino. La ley es que hay que evitar en lo posible realizar entierros en el primer día de fiesta considerado “yom tov” por la Torá, no siéndolo el segundo día para los casos de entierro. Por consiguiente se debe por lo general posponer el entierro para el segundo día de fiesta. Guíese por las leyes referentes a entierros consignadas en este “Sidur” y consulte al respecto con un verdadero rabino.

In the following paragraph, R.A. Shalem also indicates that “it is not permitted to delay or postpone the burial to the next day (i.e. to the 2nd feast day), provided that the entire service is performed by the hand of Israel”.

A. – For the love of God, do not follow these indications except in extraordinary exceptional cases and only after consultation with a real rabbi. The law is that burials should be avoided as much as possible on the first holiday considered “yom tov” by the Torah, the second day not being so for burial cases. Therefore, burial should generally be postponed to the second day of the holiday. Be guided by the laws regarding burial in this Siddur and consult with a true rabbi.

R. — ¡La ofrenda del “Omer” se hacía con la nueva cebada y no con trigo!

R. – The offering of the “Omer” was made with new barley and not with wheat!

R. — Esto se hace si el Arvit es rezado antes de la hora usual de todos los días, pero R.A. Shalem no lo explica (a los que no saben la razón y se guían ciegamente como si fuera algo cabalístico).

A. – This is done if the Arvit is prayed before the usual time every day, but R.A. Shalem does not explain it (to those who do not know the reason and are blindly guided as if it were something Kabbalistic).

R. — En los relatos históricos y del Talmud se habla de veinticuatro mil alumnos! (o doce mil pares)!

A. – The historical and Talmudic accounts speak of twenty-four thousand pupils! (or twelve thousand pairs)!

R. — ¡Todos los rabinos, menos R.A. Shalem, saben que la esclavitud de los hijos de Israel en Egipto no duró más de doscientos y diez años! (vea en la página 258 como A. Shalem todavía insiste en que la esclavitud de Egipto duró cuatrocientos años¿) (cf. mi comentario en la “Ley de Moises”, pag. 285).

A. – All the rabbis, except R.A. Shalem, know that the slavery of the children of Israel in Egypt did not last more than two hundred and ten years! (see on page 258 how A. Shalem still insists that the slavery of Egypt lasted four hundred years¿) (cf. my commentary in the “Law of Moses”, p. 285).

R. — A. Shalem dicta como ley el posar dos “sefarim” sobre la Tevá pero desconoce que la costumbre de la mayoría de los sefaradim del mundo es hacerlo solamente con uno.

A. – A. Shalem dictates as a law to place two “sefarim” on the Tevah, but he does not know that the custom of the majority of the sefaradim of the world is to do it with only one.

R. — ¡Hasta que no sepa la diferencia de “maldito sea Haman, etc.,” cuando escucha estas palabras de otros y no al pronunciarlas él mismo!

A. – Until he does not know the difference of “cursed be Haman, etc.,” when he hears these words from others and not when he utters them himself!

R. — ¡Si se encuentra el Sandak, tampoco se dicen los “Tajanunim”!

R. – If the Sandak is found, the ”Tachanunim” are not said either!

R. — ¡Aarón no rompió sus vestimentas por la muerte de sus hijos por razón de ser el Sumo Sacerdote!

A. – Aaron did not tear his garments for the death of his sons by reason of being the High Priest!

R. — Jamas se permite en “Yom Tov” (primero o segundo día de fiesta) efectuar la “Keria” aunque se trate de la muerte de padre o madre! En cuanto a “Jol Hamoed”, existe entre los rabinos una gran divergencia de opiniones y la mayoria de los “Posekim” (los rabinos por cuyos dictamenes no guiamos) son de opinión de efectuar la “Keria” en “Jol Hamoed” aunque no se trate de padre o madre. (ver “Shuljan Aruj Y.D.”, el libro “Bet Oved”, el libro “Jojmat Adam” y otros referentes a las costumbres cuando se trata de la “Keria” en “Jol Hamoed”. cf. leyes correctas de “Keria” y “Avelut” en este “Siddur”).

A. – It is never permitted on “Yom Tov” (first or second holiday) to perform “Keria” even if it concerns the death of father or mother! Regarding “Chol Hamoed”, there is a great divergence of opinion among the rabbis and the majority of the “Posekim” (the rabbis by whose rulings we are not guided) are of the opinion to perform ‘Keria’ on “Chol Hamoed” even if it is not the death of father or mother. (see “Shulchan Aruch Y.D.”, the book “Bet Oved”, the book “Chochmat Adam” and others concerning the customs when it comes to “Keria” in “Chol Hamoed”. cf. correct laws of “Keria” and ‘Avelut’ in this “Siddur”).

R. — Si estamos seguros que el pequeño completó los siete o nueve meses en el vientre de su madre (como en el caso del marido que salió de viaje a la mañana siguiente de su noche de casamiento y solo volvió después de nacer el bebé) y si este ultimo nació en estado normal con sus cabellos y sus uñas y murió dentro de los treinta días de su nacimiento, hay obligación de guardar el luto de siete días por su muerte.

A. – If we are sure that the little one completed the seven or nine months in his mother’s womb (as in the case of the husband who left on a trip the morning after his wedding night and only returned after the baby was born) and if the latter was born in a normal state with his hair and nails and died within thirty days of his birth, there is an obligation to mourn seven days for his death.

Source (Spanish) Translation (English)

“📖 סִדּוּר תְּפִלַּת מַצְלִיחַ (מנהג הספרדים) | Sidur Tefillat Matsliaḥ (Libro de Oraciones), a bilingual Hebrew-Spanish prayerbook compiled and translated by Rabbi Meir Matsliaḥ Melamed (1974)” is shared through the Open Siddur Project with a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International copyleft license.

Leave a Reply