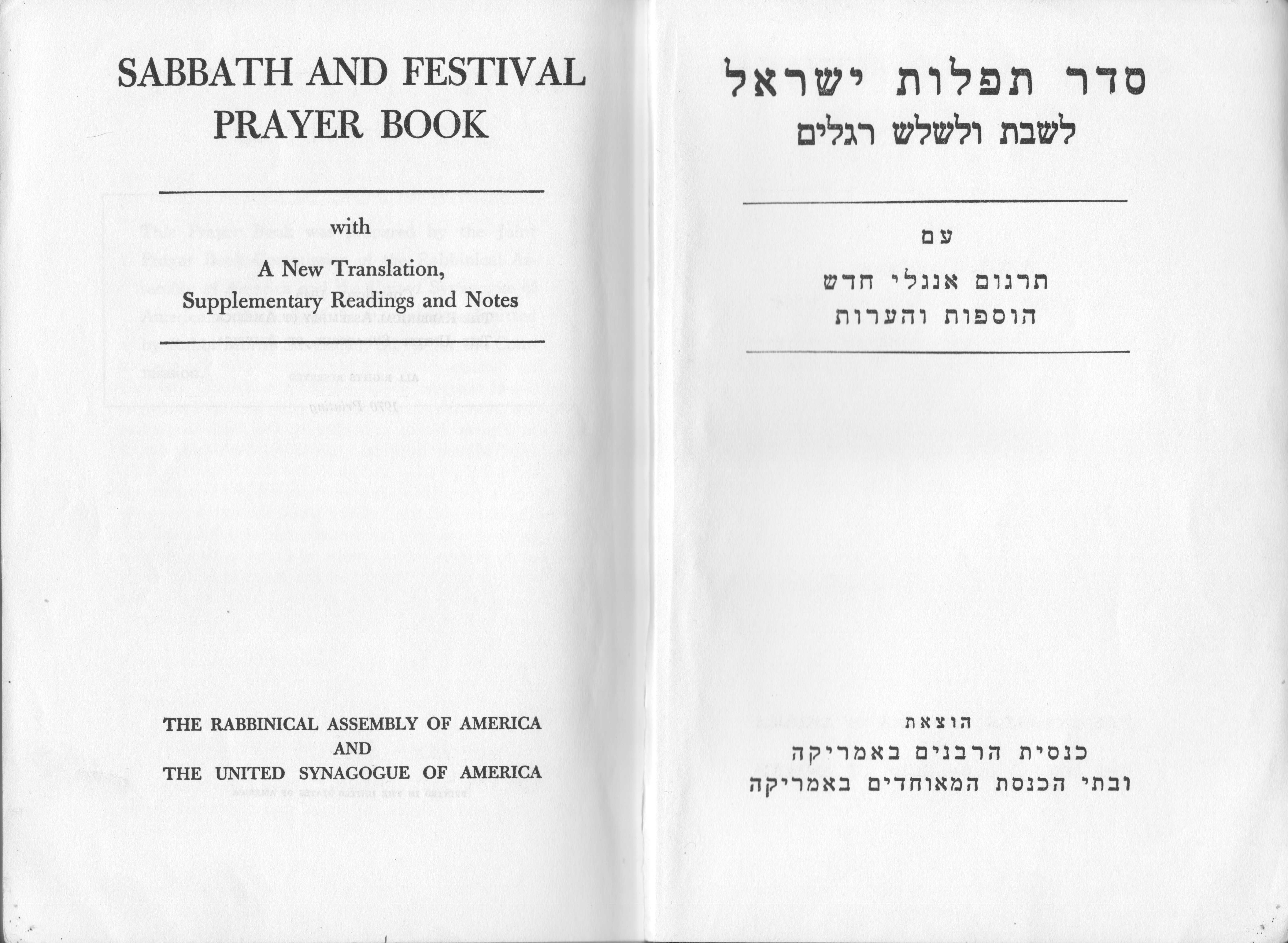

Arranged and translated by Rabbi Mordecai Kaplan, the Sabbath Prayer Book is the first Reconstructionist prayerbook we know of to have entered the Public Domain. (The prayerbook entered the Public Domain due to lack of copyright renewal by the copyright owner listed in the copyright notice, the Jewish Reconstructionist Foundation, as evidenced in the Stanford Copyright Renewal database.)

The original publication of this siddur was met by opposition from the Agudas haRabbonim, who enacted a ḥerem against Mordecai Kaplan and publicly burned a stack of this siddur. The Jewish Virtual Library provides a concise summary of the controversy:

In 1945 the Reconstructionist Sabbath Prayer Book appeared, which resulted in a ban (ḥerem) against Kaplan by the Agudat ha-Rabbonim, a small Orthodox association. Although such an attempt was largely ignored, several of Kaplan’s colleagues on the faculty of the Jewish Theological Seminary published an adverse “statement of opinion” (gillui da’at) in the Hebrew publication Hadoar. In accordance with Kaplan’s ideology, the prayerbook excised references to the Jews as the “chosen people,” and to such concepts as God’s revelation of the Torah to Moses, the parting of the Red Sea, and belief in the coming of a personal Messiah. Some passages of the traditional prayerbook were retained despite Kaplan’s rejection of the concepts which lay behind them. In such cases the editors suggested to the reader how the passages were to be understood. Thus, prayers for the restoration of Israel were retained, but readers were told this should not be construed as the return of all Jews to Palestine. Kaplan was a Zionist of the American school, ardent in his support for the colonization of Palestine, but opposed to concepts implying the “negation of the Diaspora” and to emphasis on the necessity of aliyah. The entire second half of the prayerbook contained a major innovation for the time: supplementary readings intended to allow for variety in the structure of weekly services.

Making digital scans of siddurim and other collections of prayers in the Public Domain is the first step in our process of making individual prayers (liturgy, translations, instructions, commentary, and other prayer-related work) machine-readable (copy-pastable and searchable). If you would like to take part in the transcription of this work, please join our contact us.

PREFACE

We offer to the Jewish public this arrangement of “Sabbath Services for the Modern Synagogue,” in the hope that it will advance our religious purpose to reconstruct and revitalize Jewish life. We believe that it will strengthen the spirit of faith and piety in many Jews who do not find that the prayer books now in use fully answer their spiritual needs.

The task of editing this prayer book was assumed by Rabbis Mordecai M. Kaplan and Eugene Kohn. They were assisted by Rabbis Ira Eisenstein and Milton Steinberg. The considerations which led them to edit this book and us to publish it are fully set forth in the Introduction. We gratefully acknowledge our indebtness to them and to those who assisted them in their editorial labors. Thanks are due also to Rabbi Joseph Marcus for his research work and for his translations of the English text of many of the prayers into Hebrew.

Grateful acknowledgment for permission to use published material, as well as a complete list of authors and translators whose writings appear in this prayer book, will be found at the end of the book.

Jewish Reconstructionist Foundation, Inc.

This Prayer Book is designed to offer an abundance of devotional material for Sabbath services. Its use calls for the selection of only as much material for each Sabbath as will not prolong the services beyond feasible limits. Suggestions for the use of this Prayer Book will be found in the Introduction.

INTRODUCTION[1] The views expressed here and reflected in this Prayer Book commit only the Jewish Reconstructionist Foundation, Inc. and no other institutions and organizations with which the editors are associated.

On presenting this revised prayer book, we wish to indicate what impelled us to undertake its preparation. We are well aware that great numbers of our people are attached to the traditional prayer book by sentiments of deep and sincere piety and deplore any deviation from its time-honored text. In their opinion, such deviation impairs the spiritual unity of the Jewish people and the continuity of its sacred tradition. We too are eager to preserve the Jewish worshiper’s sense of oneness with Israel and to maintain the common memories and the feeling of a common destiny, which the services of the traditional synagogue have always fostered. But due regard must be paid to certain other considerations besides the unity of Israel and the continuity of its spiritual tradition. Otherwise, Jewish worship is in danger of disintegrating, and Israel’s spiritual heritage of being dissipated.

Many modern Jews have lost, or all but lost, their sense of need for worship and prayer. They rarely attend religious services, and even when they do, their participation is perfunctory. The motions survive; the emotions have fled. The lips move, but the heart is unmoved. Unless this apathy to synagogue services is overcome, it will spell the end of worship among Jews; and the end of worship means the decay of all spiritual values and the vulgarization of human life. Since the traditional service has not sufficed to preserve the spirit of worship among Jews, we have found it necessary to suggest new forms of Jewish liturgical expression. To be sure, this need has been recognized for over a century, and various attempts have been made to satisfy it. All such attempts have been worthy efforts to revitalize Jewish worship. But we have felt that, by reason of their theology and their conception of the Jewish people, they have failed to rekindle in the Jew the spirit of worship.

That spirit depends upon experiencing the reality of God and having a sense of oneness with Israel. The profound changes, however, in life and thought during the last century and-a-half have made it necessary to restate what these experiences mean in terms of the thinking of our day. Only such a restatement can awaken in the heart of the modernminded Jew the desire to worship.

Experiencing the Reality of God

If prayer is to be genuine and not merely a recital of words, the worshiper must, of course, believe in God. He must be able to sense the reality of God vividly, as an intense personal experience. Our ancestors possessed such a sense of the reality of God, and could, without hesitation, say with the Psalmist, “I set the Lord before me continually.” The modern Jew, however, is disturbed by the current conception of nature. Nature is generally viewed as blind, mechanical and unresponsive to man’s prayers. This view of nature leaves in his mind no room for God or for worship. Therefore it is necessary for the modern Jew to strive to formulate his idea of God in terms which can serve to inspire him with faith and courage, and which at the same time conform to his knowledge of the world. Just how each Jew will conceive God will vary according to temperament and outlook. For purposes of common worship, however, it is essential to arrive at an idea of God, broad enough to bridge the differences in individual outlook and capable of resolving the inner conflicts which paralyze the impulse to pray. The following idea of God may serve as the basis of a common faith for the Jews of our day:

Reality — the sum of all that is — should not be regarded as entirely subject to forces operating mechanically. Such forces exist. Science has identified them for us and justified our confidence that they apply universally and without exception. We believe in natural law. But natural law does not account for everything. We know, for example, that, as persons, we are more than bodies acting like mechanical robots. To be sure, everything that we think, feel or do takes place through the instrumentality of our bodies and in conformity with natural law. Nevertheless, our bodies and the laws governing them do not account for all that we are. They tell us nothing of what life means for us, of our yearnings, our desires, our hopes and fears, our loves and hates. So, too, the world about us cannot be wholly explained in terms of nature. There is a universal Spirit that transcends and uses nature in some such way as the human spirit transcends and uses the bodily organs of men. Science, which concerns itself with nature’s laws, answers only the question: How? It does not answer the question: Why? It cannot tell us to what end or purpose we should direct our lives. The answer to that question, or rather the very question itself, implies a Power both in and beyond nature which moves men to seek value and meaning in life. That Power is God.

We cannot afford to live merely for the passing moment, not even for more inclusive ends confined to the brief human life-span; we must live for ends, only partially envisaged, that link us with the life of all mankind, and, beyond that, with the life of the universe, with God. Human life has worth only when its interests extend beyond the service of self. Only then do we feel that we are fulfilling our destiny as human beings and find joy in that fulfillment. Only by serving God can we achieve salvation.

Each of us should learn to think of himself as though he were a cell in some living organism — which, in a sense, he actually is — in his relation to the universe or cosmos. What we think of as a coherent universe or cosmos is more than nature; it is nature with a soul. That soul is God.

As each cell in the body depends for its health and proper functioning upon the whole body, so each of us depends upon God. Were each cell in us capable of being aware of its dependence upon the whole of us, and were it to express that awareness, such expression would for it constitute worship. Each time we hail and glorify the “Thou” in “Blessed be Thou, O Lord, our God, King of the Universe”, we enter, in however infinitesimal a degree, into communion with the Spirit that maintains the unity of life and directs that unity toward our salvation. Such communion should normally elevate our will to God’s will. Our will is to make the most of life; God’s will is that we utilize all of life’s possibilities for our salvation. This is the nearest we can get to translating the belief in God into living experience.

To God, the source of our will-to-salvation, we must turn from time to time in appreciation and gratitude for all the gifts of life, for the heritage of habits, traditions, standards and ideals, and for the accumulated wealth of tools and skills to which we are heir and by means of which we can carry further the process of universal growth and happiness. To this same source of our will-to-salvation we must turn to ward off disheartenment at the seemingly insuperable difficulties which stand in the way of universal growth and happiness. If we are to have faith in man and man’s future, if we are to have the indomitable courage to meet the onset of evil doers, if we are to be confident that the sacrifices made in behalf of a better world order are not in vain, then we must be in active communion with God of whom our best self is a minute but real emanation. To achieve that communion is the object of worship and prayer.

Having a Sense of Oneness with Israel

The prayers of the Synagogue imply the will of the worshiper to become one with the collective being of the Jewish people and its spiritual aims. The worshiper must, therefore, have a definite idea of what such oneness involves. It must mean that we are conscious of being members of the Jewish people, that we sense our kinship with it, that we accept a personal share in its history and destiny. It must mean that we recognize the unity of Israel, past, present and future, in all parts of the world. It must mean that we strive to understand Israel’s hopes and aspirations and to make them our very own. Communal worship should be the occasion for thus immersing ourselves in the living reality of kelal yisrael, the totality of Israel.

But with the advent of the Jewish emancipation, that purpose has become difficult of achievement. The Jewish people is now an integral part of the body politic of many nations. This has altered not only the political but also the spiritual status of Jewry. Our sense of oneness with Israel must, therefore, be expressed in terms which conform to modern thought and are relevant to the present situation. We must recognize that Judaism and the Jewish people have evolved and are evolving, that tradition never achieves finality, that to deprecate all change is to stunt growth. It is with a living Israel that we seek to identify ourselves, an Israel with a land, a language and a culture, an Israel that ever remakes itself in the light of changing conditions and needs.

In order that the religious services should help the worshiper achieve oneness with the Jewish people, they should, as far as possible, be carried on in Hebrew. It must, however, be a Hebrew that is understood and appreciated, and not one that is repeated by rote. Throughout this book, in addition to the traditional prayers and the readings written originally in Hebrew, the new material written originally in English appears, wherever feasible, also in a Hebrew translation.

Another means of achieving oneness with Israel is awareness of our relation to Palestine. The immemorial hope of the Jewish people to rebuild its ancient homeland is reflected throughout the text. But, in addition, much attention is given to the great contemporary enterprise of rebuilding Eretz Yisrael, as the most significant common effort of the Jewish people to realize its ideals in the modern world. The faith, the courage, the vision and the strength of the resurgent Jewish spirit are articulated in those prayers and readings which touch upon the Zionist striving. Perhaps no other cause is as potent as Zionism to kindle the feeling of oneness with the Jewish people.

Still another means towards the same end is the intimate contact with the rich cultural heritage of Israel, which spans the centuries and the vast distances that separate the modern Jew from the generations that preceded him. With that end in view, there have been brought together in this text the words of Jewish prophet and sage, philosopher and ethical teacher, poet and mystic, from many periods and many lands. Though their thoughts are couched in an idiom different from that of our day, we find expressed in them the abiding need to experience the worthwhileness of life and to achieve salvation. Since they speak the common language of the heart, they strike a responsive chord in us.

Modification of Traditional Doctrine

In order to retain the continuity of Judaism and, at the same time, to satisfy the spiritual demands of our day, it is necessary to make changes in the content of the prayer book. To preserve the authority of Jewish tradition, it is necessary to retain the classical framework of the service and to adhere to. the fundamental teachings of that tradition concerning God, man and the world. However, ideas or beliefs in conflict with what have come to be regarded as true or right should be eliminated.

Some have attempted to obviate the need for change in the traditional prayers by reading into them meanings completely at variance with what they meant to those who framed them. This practice is fraught with danger. To read those new meanings into the traditional text by way of translation is to violate the principle of forthrightness. To assume that the average worshiper will arrive at them of his own accord is to expect the unattainable. Our prayers must meet the needs of simple and literal-minded people, even of the young and immature. We dare not take the chance of conveying meanings which do not conform with the best in our religious thinking and feeling. Not that prayers need be prosaic in their literalness, but their figures of speech must have clear and true meanings. People expect a Jewish prayer book to express what a Jew should believe about God, Israel and the Torah, and about the meaning of human life and the destiny of mankind. We must not disappoint them in that expectation. But, unless we eliminate from the traditional text statements of beliefs that are untenable and of desires which we do not or should not cherish, we mislead the simple and alienate the sophisticated. The simple will accept the false with the true, to the detriment of their spiritual growth. The sophisticated will feel that a Jewish service has little value for people of modern mentality. Rather than leaving such questionable passages to reinterpretaion, we should omit or revise them.

In keeping with the foregoing, the text of the traditional prayers has been modified to bring it in line with the following changes in doctrine:

The Doctrine of the Chosen People:

Modern-minded Jews can no longer believe, as did their fathers, that the Jews constitute a divinely chosen nation. That belief carried for them the implication that the history of mankind revolved about Israel. It is not difficult to understand how they came to hold such an Israel-centered view of history. Belief in God’s choice of Israel arose at a time when all the surrounding nations were idolaters and polytheists. It expressed for our fathers their intense experience of the reality of God and their intense awareness that their people was the only nation which recognized its responsibility to the God of all mankind. This belief was later fortified by the fact that the Christian and the Moslem peoples, among whom the Jews then lived, also accepted it. They insisted however, that God had subsequently rejected the Jewish people. It became all the more necessary, therefore, for the Jews to reiterate the doctrine of Israel as the Chosen People.

In the modern world, all this has been changed by a number of political and cultural developments — the rise of democratic nationalism, the separation of church and state, the admission of Jews to citizenship and the waning belief in supernatural revelation. Thus the basis of the belief that the history of all mankind revolves about our people has been destroyed. However, even without that belief, we can and should continue as a people dedicated to the purpose of testifying to the reality of God and of serving Him. But we must acknowledge that other peoples can and should be dedicated to the same purpose.

We should, therefore, not retain the traditional text of those prayers which make invidious comparisons between Israel and the other nations. Our prayer should express a more modest conception of our role in history. The present text affirms the aspiration of Israel to make its own distinctive contribution to the enhancement of human life, but assumes the equal right and obligation of other peoples and communities to make theirs. It exhorts Israel to live up to the best of which it is capable, but avoids comparison of Israel’s achievements and capacities with those of other groups.

The Doctrine of Revelation:

Tradition affirms that God supernaturally revealed the Torah, in its present text, to Moses on Mount Sinai. But the critical analysis of the text by modern scholars and the scientific outlook on history render this belief no longer tenable. We now know that the Torah is a human document, recording the experience of our people in its quest for God during the formative period of its history. The sacredness of the Torah does not depend upon its having been supernaturally revealed. The truth is not that God revealed the Torah to Israel, but that the Torah has, in every successive generation, revealed God to Israel. It can still reveal God to us. Though we no longer assume that every word in the text is literally or even figuratively true, the reading of the Torah enables us to relive, in imagination, the experiences of our fathers in seeking to make life conform to the will of God, as they understood it. We thus make this purpose of theirs our own and are inspired to seek God also in our own experiences. And those who seek God find Him. Our discovery of religious truth is God’s revelation to us.

The study of Torah in this spirit is properly the central act of worship. It is, moreover, indispensable to our survival and growth as a people. The Torah so conceived is indeed a “tree of life” everlasting, planted within us. But it cannot serve this purpose as long as the Synagogue bases the authority of the Torah on the dogma of supernatural revelation, which the modern mind rejects. We have, accordingly, deemed it necessary to stress the sacredness of the Torah in other ways than by affirming that it was supernaturally revealed to Moses on Mount Sinai.

The Doctrine of the Personal Messiah:

Modern-minded Jews no longer look forward to the advent of a personal Messiah, who, by supernatural intervention, will redeem Israel from exile, and usher in an era of universal justice and peace. Certainly, there is still every reason to believe, as our ancestors did, that the Golden Age of mankind lies in the future, that history is morally determined, that the Kingdom of God can and will be attained in time. But we must now think in terms of universal redemption through the struggles, hopes, vision and will of all good men. Our prayer must henceforth be that Israel may contribute its share to the universal effort in behalf of a world of freedom, justice and peace.

While the prayers for the restoration of Israel’s national home are retained and even elaborated, they are not to be construed as implying the return of all Jews to Palestine. Our prayerful concern should include those who will continue to live in the lands of their nativity, and should voice the hope that they be permitted to do so in peace and freedom.

The Doctrine of the Restoration of the Sacrificial Cult:

The institution of animal sacrifice was in ancient times the accepted mode of worship, and for centuries Jews prayed for the opportunity to reinstate that mode of worship in a rebuilt Temple in Jerusalem. Instead of the prayers which express that hope, the present text contains the prayer that we may learn to make sacrifices of our resources and energies in behalf of worthy causes, and that a restored Eretz Yisrael may once again inspire us to serve God.

Since the distinctions between Kohen, Levi and Israelite have always been associated with their respective functions in the Temple cult, these distinctions are no longer cogent. All references to them as still playing a part in Jewish life are omitted.

The Doctrine of Retribution:

Our ancestors believed that obedience to the moral and ritual laws of the Torah resulted in favorable rainfalls; and that disobedience caused the rain to be withheld. This was undoubtedly an aspect of their intuition that the moral law was as integral to the structure of the universe as natural law, and that both kinds of law were interwoven in the destinies of men. To the extent that obedience to the moral law spells happiness and peace for mankind, and disobedience spells disaster and war, that intuition was correct. But that the very rainfall is influenced by human conduct, we know, is not true. The present text, therefore, is so modified as to emphasize the ever timely truth that the material prosperity and well-being of society depend on its conforming to the Divine law of justice and righteousness.

The Doctrine of Resurrection:

Men and women brought up in the atmosphere of modern science no longer accept the doctrine that the dead will one day come to life. To equate that doctrine with the belief in the immortality of the soul is to read into the text a meaning which the words do not express. That the soul is immortal in the sense that death cannot defeat it, that the human spirit, in cleaving to God, transcends the brief span of the individual life and shares in the eternity of the Divine Life can and should be expressed in our prayers. But we do not need for this purpose to use a traditional text which requires a forced interpretation. This prayer book, therefore, omits the references to the resurrection of the body, but affirms the immortality of the soul, in terms that are in keeping with what modern-minded men can accept as true.

The revision of the traditional prayers to conform to the foregoing changes of doctrine should advance the major purposes of this prayer book. That revision should help the worshiper to experience the presence of God in his personal and communal life. And it should so unite the worshiper with Israel as put him in possession of the living truth which Israel has learned concerning man’s task on earth.

The Proper Use of the Prayer Book

To achieve the foregoing purposes, both rabbi and congregation should study how to make the best use of this prayer book. Each service should be carefully planned by the rabbi. Those parts of the service which are indicated by larger type should be read every Sabbath, but the additional parts should not be chosen at random. They should conform to some central theme suggested by the portion of the week, by the subject of the rabbi’s sermon or by a significant current event. Care should be taken to create a balanced service, one that observes a due proportion between the new and the familiar, between singing and reading, between silent meditation and oral utterance. Used in that way, the book can help to overcome the tendency to automatism into which communal worship is so liable to fall.

In planning the services, the Supplement should prove helpful and, indeed, indispensable. The prayers, readings and hymns contained in that section of the book are taken from a large variety of sources. Some of the texts are not new, but are new to the prayer book. They are classics of the Jewish religious genius, wasting far too long their inspiration upon the shelves of neglected libraries. Others are the products of the modern Hebrew renaissance. Still others were composed by the editors themselves.

Some of these texts give new and varied expression to hopes and aspirations of the human spirit which are eternal; others reflect contemporary needs. The variety of prayer content in the Supplement is designed to insure the freshness so essential to an effective service.

As for the congregation, its men and women should strive to’ create a common emotional mood by participating in the service to the maximum degree. The service must not become a performance, nor the congregation an audience. As many as possible should learn to read Hebrew and should join in congregational singing. They should give close and concentrated attention to the meaning of what they are saying or singing. Our sages cautioned against the tendency of prayer to deteriorate into a mere formality and to lose its character of worship: “Let not your prayer become a mere routine, but let it be a yearning for mercy and grace in God’s sight. And applying to worship a favorite principle of theirs, we should conclude that it matters not whether one says many prayers or few, provided one prays with a heart intent on serving God.

Those who wish to use this prayer book should engage beforehand in a careful study of it, so that they may come to the services sensitized to their beauty and meaning. To facilitate the recognition of the underlying thought in each prayer, descriptive titles have been provided in this book.

Attention to these titles will give one a comprehensive idea of the religious content of Judaism and will help one learn to pray with devotion.

With these suggestions and explanations, we submit this prayer book, in the hope that it will render Jewish communal worship once again a source of inspiration to faith and spiritual purpose.

The Editors.

Notes

| 1 | The views expressed here and reflected in this Prayer Book commit only the Jewish Reconstructionist Foundation, Inc. and no other institutions and organizations with which the editors are associated. |

|---|

“📖 ספר תפילות לשבת | Sabbath Prayer Book, by the Jewish Reconstructionist Foundation (1945)” is shared through the Open Siddur Project with a Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication 1.0 Universal license.

Leave a Reply