“The wicked child asks: What does this work mean to you? Mah ha’avodah ha’zot lachem” (Exodus 12:26). I think about this question a great deal as a rabbi whose core work involves fighting modern-day slavery. I think about it when I talk to my children about what I do every day, when I call anti-trafficking activists and say, “What can rabbis do to support you?” or when I stand before Jewish audiences and urge them to put their energy behind this critical human rights issue.

The answer must go deeper than simply saying, “We were slaves in Egypt once upon a time.” The memory of bitterness does not necessarily inspire action.

What inspires me is not slavery but redemption. God could part the Sea of Reeds, but the Israelites could not truly be free until they had liberated themselves, after 40 years in the desert, from slavery.

I have personally been transformed by my experiences organizing T’ruah’s #TomatoRabbis partnership with the Coalition of Immokalee Workers (CIW) in Florida. Their starting question–What would a slavery-prevention program look like if it were designed by the workers themselves?—challenged me to think differently about what it means to fight to end modern slavery. I needed to get beyond repeating stories of exploitation and move toward supporting efforts to rebuild lives and resolve root causes. And I had to ask myself, “What does this work mean to me, as an ally? Why am I here?”

This hagaddah represents T’ruah’s collective wrestling with Mah ha’avodah ha’zot lachem. We began our campaign to fight modern-day slavery in 2009, by raising awareness in the Jewish community about this human rights struggle and mobilizing synagogues to take action locally. We quickly learned deeper questions: not just “how do we teach people that slavery still exists?” but “how can we better support survivors?” and “how can we move from being consumers to being activists?”

I am deeply grateful to Rabbi Lev Meirowitz Nelson, T’ruah’s Director of Education, for distilling these theological and practical questions into this amazing hagaddah. I also want to thank Rabbi Jill Jacobs, T’ruah’s Executive Director, for the leadership and vision that made this haggadah possible. Finally, many thanks to the rabbis and activists whose reflections serve as the commentary to the hagaddah, and the more than fifty #TomatoRabbis who have visited with the CIW in Immokalee, FL and have led the Jewish community to partner with these leaders. You have taught me so much and I am grateful to be able to share your wisdom with the Jewish community.

This hagaddah is designed so that it can both be used as a complete anti-trafficking seder or incorporated in whole or in part into your seder at home. May this hagaddah inspire all of us to new questions and to build a world of lovingkindness.

Rabbi Rachel Kahn-Troster

Director of Programs

Adar 5775/March 2015

Order of the Seder

קַדֵּשׁ וּרְחַץ כַּרְפַּס יַחַץ מַגִּיד רָחְצָה מוֹצִיא מַצָּה מָרוֹר כּוֹרֵך שֻׁלְחָן עוֹרֵךְ צָפוּן בָּרֵךְ הַלֵּל נִרְצָה |

Ḳadesh (Sanctifying) Ur’chatz (Preparing) Karpas (Salting) Yachatz (Breaking) Maggid (Telling) Rachtzah (Blessing) Motzi Matzah (Partnering) Maror (Empathizing) Korech (Sweetening) Shulchan Orech (Eating) Tzafun (Searching) Barech (Thanking) Hallel (Singing) Nirtzah (Committing) |

How to use this Hagaddah

The haggadah is a starting point for conversation. Here are some ideas for making your seder interactive:

- Plan ahead. Read through the whole haggadah, and make notes about which sections you will emphasize, where you want to spark discussion, and where you will include rituals, songs, or other activities. Good planning will also help you pace yourself so that you don’t end up rushing at the end.

- Focus on the sections of the hagaddah that resonate with you the most. It is better to incorporate fewer sections more deeply than to skim through the whole haggadah superficially.

- Alternate between large group discussion and more intimate conversation within small groups of guests.

- Balance discussion, singing, and ritual. Different people will find different approaches meaningful.

- Before the seder, connect with local anti-trafficking organizations and ask them what action steps or volunteer opportunities would be helpful to them. When seder participants get excited about taking action, you’ll have some ideas to share.

- Contact T’ruah at office@truah.org or 212-845-5201 to talk more about how to use this haggadah, or about how to involve your community in efforts to end trafficking.

The first time I heard a trafficking survivor speak many years ago, she told the story of her parents trafficking her for sex from the time she was a young girl until she was an adult. I sat in horror, listening to her calm recollection of how both her mother and father trafficked her, sometimes leaving her for days at a time in a makeshift brothel when she was barely old enough to read and write.

Her story was my T’ruah – a decibel-defying call to action to open doors, pull back curtains, and shout from the rooftops the pain and suffering of trafficked individuals in our midst.

The call guides my work at the National Council of Jewish Women, alongside incredible and passionate advocates around the country, to raise awareness about trafficking in the United States, where children are bought and sold in every state, 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. And the call informs my work to create lasting social change through legislative advocacy – working with lawmakers to address the systemic issues that allow trafficking to exist, including lack of education and opportunities, and passing legislation to reform the child welfare system, which effectively serves as a supply chain to traffickers.

The sound of the shofar, a sign of liberation, reminds me not only of one woman’s unspeakable journey, but of my greater responsibility to ensure my call becomes a collective call to action for all of us in the Jewish community.

– Jody Rabhan, Director of Washington Operations, National Council of Jewish Women

וּרְחַץ Ur’chatz

“The beauty of Ur’chatz was revealed to me during a women’s seder. Each participant washed the hands of another with care and kavvanah (intentionality)—and without words. The sisterhood created in the sacred silence elevates communal consciousness. How will we utilize this state of purity? V’ahavtah l’re’echa kamochah – to love the other as ourself.

How will this ancient wisdom propel us forward to empower the silent? How will we elevate the hands of all those still in Mitzrayim?”

– Jessica K. Shimberg, Spiritual Leader, The Little Minyan Kehilla, Columbus, OH; ALEPH Rabbinical Program Class of 2018

קַדֵּשׁ Ḳadesh

We begin our seder with the Ḳiddush, the sanctification of this moment in time.

The text of the Ḳiddush reminds us that the choice to uphold the sacred is in our hands. We do not directly bless wine, or praise its sweetness. Rather, we thank God for the fruit of the vine. That fruit can also be used to make vinegar, which is sharp and bitter. Our actions determine whether this sacred moment in time inspires bitterness or sweetness, complacency or action.

Bless and drink the first cup of wine/grape juice.

בָּרוּךְ אַתָּה ה’ אֱלֹהֵינוּ מֶלֶךְ הָעוֹלָם בּוֹרֵא פְּרִי הַגָּפֶן. |

Baruch atah Adonai Eloheinu Melech haOlam boreh pri hagafen. Blessed are You ETERNAL our God, Master of time and space, creator of the fruit of the vine. |

כַּרְפַּס Karpas

As the Four Questions will soon point out, we dip twice in our seder. The two dippings are opposites. The first time, as we prepare to enter a world of slavery, we dip a green vegetable into saltwater, marring its life-giving freshness with the taste of tears and death. The second time, as we move towards redemption, we moderate the bitterness of maror with the sweetness of charoset.

Any time we find ourselves immersed in sadness and suffering, may we always have the courage to know that blessing is coming.

בָּרוּךְ אַתָּה ה’ אֱלֹהֵינוּ מֶלֶךְ הָעוֹלָם בּוֹרֵא פְּרִי הָאֲדָמָה. |

Baruch Atah Adonai Eloheinu Melech haOlam boreh pri ha’adamah. Blessed are You ETERNAL our God, Master of time and space, who creates the fruit of the earth. |

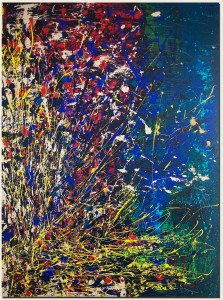

“During my enslavement, the moon was a constant in my life. Its light was a safe harbor in my darkness. It gave me hope. I would look at it and not feel alone. Something about its glow made me believe in the light of others. It allowed me to feel confident that not all humans would abuse and devalue me.” Margeaux is a survivor of domestic child sex trafficking. Much of her artwork incorporates everyday items that other people might consider trash. This serves as a symbol that people whom our society might be ready to discard—among them people forced into human trafficking—remain creatures of value and beauty. Margeaux has transcended her experience as a trafficking victim, and today she is an advocate, motivational speaker, and artist.

Visit her website: margeauxgray.com

Rav Kook taught that the entire Haggadah centers on the biblical verse “You shall tell your child on that day, ‘Because of what the Eternal did for me when I went free from Egypt’” (Exodus 13:8), which we use to answer the wicked child and the one who does not know how to ask.

Maybe that means that all I have to do to fulfill my obligation to see myself as if I were personally liberated from Egyptian bondage is to say this line.

No way! When I say “what the Eternal did for me,” a robust seder depends on imagining the taskmaster’s lash, the Israelite hope for God’s compassion, and the sweet taste of freedom’s tears of joy on the far side of the Sea.

And yet, I am only imagining the move from degradation to redemption. My freedom to imagine a life of slavery is itself a form of privilege. As we engage the issue of modern slavery, let us constantly be aware of the privilege we bring as well as the power, so that we may take up the right amount of space at the table and no more.

– Rabbi David Spinrad, The Temple, Atlanta, GA

As we begin Maggid, we seek to enter into the experience of slavery and redemption with more than just our heads, but with our hearts and bodies as well.

Claudia writes, “The shroud represents freeing people from the imprisonment of their minds and bodies. There is always a shroud covering the essence of truth within.” Claudia’s reflection on her life as a trafficking survivor can be found below.

יַחַץ Yachatz

Rabbi Zalman Schacther-Shalomi z”l taught that the “big matzah” represents the “big lessons,” which we can only take in and digest through the experience of the seder.

When we break the matzah, we traditionally save the bigger piece for the Afikomen. This year, let’s save only the smaller piece.

We obviously haven’t quite grasped the “big lessons” of the seder. If we had, we would not allow slavery in the world today. So, this year, we take the small piece. We commit to earning the big piece by next year.

– Rabbi Debra Orenstein, Congregation B’nai Israel, Emerson, NJ

When my grandfather broke the middle matzah, a hush fell over our Seder. All the cousins fell silent, concentrated on the navy velvet pouch between our Poppy’s wrinkled hands. Before slipping out to hide the Afikomen, he invited us to touch the pouch. Filled with promise, each of us reached out. As we brushed our fingers against the soft fabric, we simultaneously felt the warmth of our grandfather’s hand on our heads, a gentle touch of confidence for each grandchild. Then he was gone and the silence broken. The background sounds of the Seder would slowly rise in decibel as the adults’ attention turned away, even as the children stayed silent, quietly waiting or gesturing strategy. My grandfather’s return inaugurated the grand search, breaking the pressure of anticipation and unleashing indescribable exuberance.

To me, Passover is about the hopefulness I felt as a child in the moment that my Poppy opened the door and we rushed out to search for the coveted velvet pouch. It is that same hopefulness, those same touches of confidence, and that same exuberance that inspire my belief that change is possible, that we can make an impact on modern slavery in my lifetime.

– Melysa Sperber, Director, Alliance to End Slavery and Trafficking

In March 2013, a few weeks before Passover, I participated in CIW’s March for Fair Food with my older daughter, Liora. Early one morning, as dawn broke and we sat on a bus bearing a banner “No more slavery in the fields,” she asked me to practice the Four Questions, which she would recite at the seder very soon. In that moment, past and present came together. Listening to her chant in Hebrew mah nishtanah ha layla hazeh, why is this night different from all other nights, I understood the power of the commitment we make as Jews each year. We cannot tell the story of slavery without committing to action in the present day. And we are blessed to know that today real solutions are possible.

– Rabbi Rachel Kahn-Troster, Director of Programs, T’ruah

מַגִּיד Maggid

Fill the second cup and begin Maggid.

Four Questions About Modern Slavery

We start the seder by noticing what is out of the ordinary and then investigating its meaning further.

How is this night different from all other nights?

On all other nights, we depend on the exploitation of invisible others for our food, clothing, homes, and more.

Tonight, we listen to the stories of those who suffer to create the goods we use. We commit to working toward the human rights of all workers.

On all other nights, we have allowed human life to become cheap in the economic quest for the cheapest goods.

Tonight, we commit to valuing all people, regardless of their race, class, or circumstances.

On all other nights, we have forgotten that poverty, migration, and gender-based violence leave people vulnerable to exploitation, including modern-day slavery.

Tonight, we commit to taking concrete actions to end this exploitation and its causes.

On all other nights, we have forgotten to seek wisdom among those who know how to end slavery—the people who have experienced this degradation.

Tonight, we commit to slavery prevention that is rooted in the wisdom and experience of workers, trafficking survivors, and affected communities.

When the seder has ended, we will not return to how it has been “on all other nights.” We commit to bringing the lessons of this seder into our actions tomorrow, the next day, and every day to come.

Claudia writes, “During my ordeal, I was in a constant state of hyperawareness, because I had to be ahead of the abuser. Sleeping was when I was vulnerable. This signifies that I was awake and ready to escape, to be free.” Claudia’s reflection on her life as a trafficking survivor can be found below.

All faith begins with the act of questioning. From God’s first question to Adam and Even in Eden – Ayekah, “Where are you?” – to Abraham’s challenge to God concerning Sodom and Gomorrah, to Sarah’s exasperating and agonizing question about whether she would ever bear children, to Moses questioning Pharaoh’s authority, the Jewish people have always been intoxicated with the art of questioning.

Perhaps we who were slaves are constantly in a state of remembering the degradation and seeking never to forget. It is the privilege of free people to ask questions; this is the birthplace of our compassion and our zeal for justice. Why else might a motley band of former slaves have taken it upon ourselves to demand that humanity live up to its sacred promise for equality and dignity for all God’s creation?

– Rabbi Michael Adam Latz, Shir Tikvah Congregation, Minneapolis, MN

RABBIS IN ACTION

In December 2013, I visited a local Wendy’s restaurant with our Middle School students. We did not do so to grab a snack, but to take a stand for human rights. We were urging Wendy’s to join the Coalition of Immokalee Workers’ (CIW) Fair Food Program.

Our task was not to be a menace, but to have meaningful conversations to create change. The manager knew we were coming and was happy to hear my students express their concerns about the exploitation of workers in Florida tomato fields. After talking with the manager, we handed her letters to pass along to the corporate office. She assured us that she would speak to her superiors and share our concerns.

We then left and gathered our posters and signs to raise awareness outside the restaurant. This was just one afternoon and one action, but it was an afternoon that inspired me. I now believe that these students will not just learn our tradition, but also live its values, ensuring equality and human rights for all.

– Rabbi Jesse M. Olitzky, Congregation Beth El, South Orange, NJ

The Four Children

When we talk about modern-day slavery, we all start out as the child who does not know to ask, because we don’t even know that the problem exists. Upon first encountering the issue, we ask simple questions. As we learn more, it is easy to slide into the frustration of the wicked child: this is such a massive uphill battle and I am so small—why should I bother caring? We seek the wisdom to overcome despair and find the ways in which we can be effective at fighting the root causes of modern slavery.

On the path from first realizations to paralysis to activism, where do you find yourself tonight? What has your journey been to this place?

The seder demands that we look forward, not backward. To the children’s questions about why we celebrate Passover, we respond, “because God took us out of Egypt“ and not “because we were slaves in Egypt.” We dwell on the joy and agency of liberation, not on the pain of slavery.

Anchored in the Present, Rooted in the Past

Ha lachma anya encapsulates the past (the bread we ate in Egypt), present (let all who are hungry come eat), and the future (as free people in the Land of Israel). The four questions then anchor us in the present—what is different this night?—before Avadim Hayinu sends us back in time to explore our origins.

Our understanding of human trafficking must also be rooted in history and the origins of worker exploitation.

“You shall tell your children on that day.” When we participate in the Seder, we fulfill a covenant with history to celebrate freedom. But to treat this covenant only as treasured memory is to divest it of its essence. The covenant is also a promise we make to the present and the future. When we say, “What God did for me,” we recognize the illegitimacy of bondage for all people. These too need a strong hand and an outstretched arm—the Indian family in debt bondage; the Congolese man enslaved in a mine; the Nepali woman in a brothel; the Haitian girl in domestic servitude; the Ghanaian boy trapped on a fishing boat.

When we ask, “Why is this night different from all other nights?” let us answer, “We keep faith with the heritage given to us by Moses by helping to liberate those who are slaves in our time.” As Moses says in Deuteronomy 30:11, “This is not too difficult for you.” Everyone can contribute to ending bondage. Participating in the abolition of slavery in our time adds meaning and joy to the Seder.

– Maurice Middleberg, Executive Director, Free the Slaves

Rav Nachman asked his slave Daru, “What should a slave say to his master who has freed him and given him silver and gold?” Daru replied to him: “The slave should thank him and praise him!” Rav Nachman said to Daru: “You have exempted us from reciting ‘Ma Nishtana’!”

(Babylonian Talmud, Pesachim 116a)In the exchange above, Rav Nachman is speaking allegorically of the Passover Haggadah. But Daru understands him literally. Based on what Rav Nachman just said, Daru anticipates his imminent liberation by his master, but Rav Nachman is merely musing on the minutia of the Passover Haggadah’s myths and rituals.

Following Daru’s excited and hopeful response, Rav Nachman resumes his own (disconnected) allegorical reflections on what ought to be recited on this Passover night. Despite the immediate presence of a real-life slave right before him, Rav Nachman remains pitifully oblivious to the struggles, hopes, and overall reality of his own servant.

JTS Talmud Professor Rabbi David Hoffman teaches that this exchange between Rav Nachman and Daru is a story about us. It is about the fundamental dissonance between the story we are living and the story we are telling. Especially today, as we are no longer an oppressed, enslaved nation, we can use our resources and power to overturn structures of abuse right before us. On this Passover night, let us heed Daru’s call and answer it—wherever he is in our lives.

– Raysh Weiss, PhD, JTS

Rabbinical School class of 2016; T’ruah board member and summer fellowship alumna; BYFI ‘01

“In the beginning, our ancestors worshipped idols”

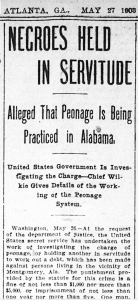

Use the following four images/texts as a starting point for a conversation about the Legacy of American Slavery.[1] Courtesy of PBS, Slavery by another name.

- It may be surprising to learn that slavery existed into the 20th century. Why do you think it was able to persist?

“We used to own our slaves. Now we just rent them.” – Florida grower quoted in the film

2. Do this picture and this quote surprise you? Why or why not? What do they teach us about the legacy of slavery in the United States?

A 1903 fine of $1000-$5000, in 2013 dollars, would be worth roughly $60,000-$300,000.[2] Based on http://www.measuringworth.com/uscompare

Timeline of types of slavery in America

17th-18th century

Indentured Servitude Poor, often white immigrants from Europe were bound to work for a set number of years. They were often mistreated or held for longer than their period of indenture.

17th century-1865

Chattel Slavery

The purchase and sale of Africans as slaves.

1865-1944

Convict Leasing

Prisoners were leased out as workers to private (white) citizens. These prisoners were overwhelmingly black and had often been arrested on flimsy charges, such as vagrancy.

Mid 19th-mid 20th century

Sharecropping

Black tenant farmers worked a portion of the owner’s land, in exchange for a share of the crop. They had to purchase supplies and seeds from the owner. Tenants, often illiterate and at the mercy of unscrupulous landowners, frequently ended up only breaking even—or even further in debt—at the end of a season.

TODAY

Examples of Modern-Day Slavery

U.S. vs. Bontemps, July 2010. Cabioch Bontemps and two others indicted by a federal grand jury on charges of conspiracy to commit forced labor, holding 50+ guestworkers from Haiti against their will in the beanfields of Alachua County, FL. They held the workers’ passports and visas. The indictment states that Bontemps raped one of the workers and threatened her if she reported it. The Coalition of Immokalee Workers trained law enforcement and helped with the referral to the Department of Justice. DOJ dropped the charges without explanation, though likely due to legal technicalities, in January 2012.

Unable to leave the house. Forbidden to answer the door. Cut off from her family. Worked fourteen to sixteen hours per day. Paid nothing. Threatened with deportation and harm to her family. Someone called in a tip. She escaped.

Another tipster called the national hotline. She reported a woman in the neighborhood who never left the house, except to take out the trash. The FBI investigated. The woman had been held in forced labor for four years.

Involuntary servitude among domestic workers and nannies is one of America’s most hidden crimes. Like domestic violence, it occurs behind closed doors. Like trafficking into other sectors, the victimization can involve rape and sexual violence. Like other forms of trafficking, the abuse leaves deep scars. Unlike most trafficking, some of the perpetrators are diplomats, who bring in domestic workers on special visas.

Domestic workers are among the most exploited workers in the world. Over the years, trafficking victims have told me they never expected to be exploited here. “Not in America,” many have said. “That does not happen in America.” But it does. In America. And all around the world.

– Martina Vandenberg, Founder and President, Human Trafficking Pro Bono Legal Center

- What do you notice about this picture? Does anything surprise you? What does this picture tell you about trafficking in the United States today?

This looks like an ordinary apartment building in Los Angeles, but in fact it’s a sweatshop in which seventy-two Thai women were enslaved for eight years, from 1987-1995.[3] For more information: http://www.sfgate.com/news/article/70-Immigrants-Found-In-Raid-on-Sweatshop-Thai-3026921.php and http://americanhistory.si.edu/sweatshops/elmonte/elmonte.htm. One of the extraordinary and heartbreaking aspects of this case is the crimes the traffickers were charged with—all relating to facilitating illegal immigration, rather than modern slavery—and the fact that, at least initially, the survivors were threatened with deportation if they were found to be undocumented. Since the passage of the Trafficking Victims Protection Act in 2000, both perpetrators and survivors would be treated differently. A group of traffickers lured the women in with promises of good wages, then forced them to work up to eighteen hours a day making clothing for well-known brands for leading department stores. The workers were not allowed to leave the compound.

- Thanks to a 2005 Congressional report, we know that slaves participated in the building of the Capitol. What does the juxtaposition in this image say to you about our country?

Photo by Fritz Myer, June 2010, Courtesy of the Coalition of Immokalee Workers. Note the title on the truck.

- How do we benefit today from the legacy of slavery in this country?

Slavery was “normal,” constitutional. Slavery built the USA. Slavery is regulated, that is to say allowed, in our Talmud. In 1861, when Reform Rabbi David Einhorn preached, “Is it anything else but a deed of Amalek, rebellion against God, to enslave human beings created in His image?” he was driven from Baltimore by a mob that included Jews. Orthodox Rabbi Sabato Morais went beyond the halakha of his day, in 1864, to thunder, “What is Union with human degradation? Who would again affix his seal to the bond that consigned millions to [that]? Not I, the enfranchised slave of Mitzrayim.” Today it is disruptive to ask—and keep asking when ignored—“Who grew this food we’re eating? Who sewed our clothes?” Even more disruptive to answer and then say that our tradition calls us to act. Do I have the guts to emulate our gedolim and disrupt what’s normal?

– Rabbi Robin Podolsky, Senior Adult Educator, Temple Beth Israel of Highland Park and Eagle Rock, Los Angeles, CA

Every Passover, I sit with my friends and family to tell the story of our people’s liberation from slavery in Egypt. As we tell the story, we are asked to imagine that we ourselves were once slaves in Egypt and now we are free.

As an African-American, during Passover, I often think about my ancestors who were brought to this country as slaves. I imagine they found comfort in the biblical story of the Exodus; seeing themselves as the Israelite slaves and the slave owners as the Pharaoh. I imagine them praying to God for freedom and never giving up hope.

As a Jew and an African-American, I carry the memories of people who were once enslaved. I hold on to our collective memory of our escape from Egypt to freedom. And like my ancestors, I pray for the freedom of all who are enslaved, and I am hopeful that next year we will all be free.

– Sandra Lawson, Reconstructionist Rabbinical College Class of 2018, T’ruah summer fellowship alumna

Summing Up: How We Remember America

- What do these verses teach us about forgetting and remembering?

America prefers to whitewash its history of slavery. What do we most often remember about the history of slavery in America? What do we most often forget? Why do you think this is the case?

The sequence of verbs is: God hears, remembers, sees, and knows. We often need to have multiple kinds of contact with an issue before it sinks in for us. What is your experience—what does it take to move you from hearing about an issue to internalizing and acting on it?

Rabbi Lance J. Sussman, senior rabbi at Reform Congregation Keneseth Israel in Elkins Park, Pa., and visiting professor of American Jewish history at Princeton, [says]…The Passover narrative…didn’t become an abolitionist-related story until after World War II and the Civil Rights era. “Originally, Passover was theological. It’s about redemption and the power of God. It’s not really about setting human beings free in a universal way. The text says that God frees the Hebrew slaves because God loves the Hebrews. God doesn’t free all slaves for all of humanity or send Moses out to become the William Lloyd Garrison of the ancient free world.”[4] “Passover in the Confederacy,” by Sue Eisenfeld, The New York Times, 4/17/2014

Although few Jews, like other Americans, opposed slavery at the [Civil] war’s outset, many came to feel that the suffering of the war needed to be about something important: the end of slavery and the creation of a different America…As historian Howard Rock sums up, “The war was a transformative moment for Jews’ understanding of American democracy.”[5] “Jews Mostly Supported Slavery—Or Kept Silent—During Civil War,” by Ken Yellis, The Forward, 7/5/2013

- Do you think the Passover story is a helpful lens through which to view America today? What are some of the strengths and weaknesses of this paradigm?

וַיָּקָם מֶלֶךְ־חָדָשׁ עַל־מִצְרָיִם אֲשֶׁר לֹא־יָדַע אֶת־יוֹסֵף׃ |

“A new king arose over Egypt who knew not Joseph.” (Ex. 1:8) |

וַיִּשְׁמַע אֱלֹהִים אֶת־נַאֲקָתָם וַיִּזְכֹּר אֱלֹהִים אֶת־בְּרִיתוֹ אֶת־אַבְרָהָם אֶת־יִצְחָק וְאֶת־יַעֲקֹב: וַיַּרְא אֱלֹהִים אֶת־בְּנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל וַיֵּדַע אֱלֹהִים׃ |

“God heard their cry, and God remembered God’s covenant with Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. God saw the Israelites and God knew.” (Ex. 2:24-25) |

Margeaux writes, “My story of rising above slavery and the unjust violence I experienced inspired this piece. Additionally, my ancestors and those who paved a path for my freedom to be possible were also an influence in its creation. The carved painting is of a woman connected to her ancestors. She draws from their strength and wisdom. She is empowered by them and rises above the oppressive nature that has for so long silenced her. She breaks through a wave and steps into the light of freedom.”

As we sing “Vehi she-amda,” we remember that in every generation, people have been held as slaves, and God has been their support, if not their complete redemption.

In Hebrew, “The One” in the song is feminine. Who is this One? The classical rabbis would probably say the Torah. The Kabbalists invoked Binah, a feminine aspect of God. In the spirit of 70 faces of Torah, here is a slightly subversive suggestion: the one who stood up for our ancestors—literally, our fathers—is our mothers. We remember the oft-erased contribution women have played throughout history and celebrate the importance and power of women’s leadership in fighting slavery today.

וְהִיא שֶׁעָמְדָה לַאֲבוֹתֵינוּ וְלָנוּ שְׁלֹא אֶחָד בִּלְבַד עָמַד עָלֵינוּ לְכַלֹּתֵינוּ אֶלָּא שֶׁבְּכָל דּור וָדוֹר עוֹמְדִים עָלֵינוּ לְכַלֹּתֵינוּ וְהַקָּדוֹשׁ בָּרוּךְ הוּא מַצִּילֵינוּ מִיָּדָם. |

Vehi she-amda, vehi she-amda la’avoteinu velanu (x2) She-lo echad bil’vad amad aleinu lechaloteinu Elah she-bechol dor vador omdim aleinu lechaloteinu Vehakadosh baruch hu matzileinu miyadam. This is the One who stood up for our ancestors and for us. |

RABBIS IN ACTION

At Yavneh’s core is the belief that the Jewish values and ethics the students learn are only realized when put into action, so integrated throughout our curriculum are opportunities to practice these values in real life situations. Specifically, our middle school students engage in a three year Jewish social justice curriculum, in which they examine how they can contribute to the world, responding to the needs of their own community through direct service and making a difference globally through philanthropy and advocacy.

T’ruah’s Human Rights Shabbat has become an annual tradition at our school, in which our middle school students teach the elementary school students.

In the last few years, we have closely examined the issue of human trafficking in America and the Jewish teachings that categorically make it an imperative for Jews to be involved. Our students have made tomato plates for their seder tables; engaged in inter-disciplinary learning researching the history of agriculture in America, calculating fair wages, and writing letters to Congress; and created presentations to raise awareness in the community.

– Rabbi Laurie Hahn Tapper, Director of Jewish Studies and School Rabbi, Yavneh Day School, Los Gatos, CA

RABBIS IN ACTION

A few years ago, as the Washington State Legislature was considering a bill on human trafficking, I sought out the sponsoring Senator and offered my testimony, as a member of the clergy, in support of the bill during the public hearing. While others spoke of the facts of human trafficking, and a victim shared her story, I offered a spiritual and ethical message based in Jewish teachings. Sitting in that hearing room to share this simple yet fundamental message felt like an important opportunity we have as rabbis to effect change, and to share a message our lawmakers need to hear more often: that lawmaking is as much a moral act as it is a legal act.

– Rabbi Seth Goldstein, Temple Beth Hatfiloh, Olympia, WA

Organizations that have lobbying arms, such as the local Jewish Federation, can often help connect community leaders with opportunities to give testimony.

Wanting to go home, wanting to stay

“I just got my green card! Now I can go to the Philippines. And finally hold my son. I want to be there before his birthday…I waited for this. I never complained. I’ve suffered so much. But I never did anything to the people who hurt me…My boyfriend wanted to go out and celebrate. I said, ‘Let me be for a while.’ I needed to think about it.” -Maria, trafficked from the Philippines for domestic labor; Life Interrupted, p. 146.

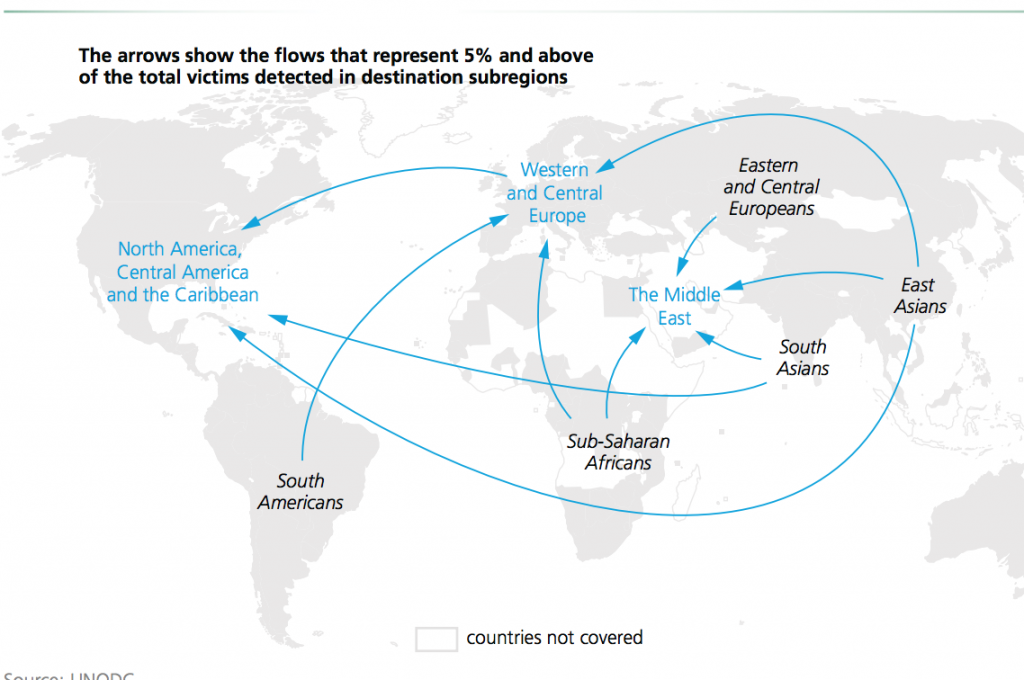

The arrows show the flows that represent 5% and above of the total victims detected in destination subregions. From UN Office on Drugs and Crime, based on 2014 Trafficking in Persons Report. According to UN Dispatch, “most trafficking occurs within a region” and is therefore not recorded on this map.

Good data are hard to come by, but a conservative estimate by the International Labor Organization puts the total number of enslaved people worldwide at 21 million.

• What populations would you think are especially vulnerable to enslavement?

• Does anything surprise you about this map?

“VaNitz’ak el Adonai Elohei Avoteinu”—We cried out to the God of our Ancestors

“Tzeh Ul’mad” – Go Out and Learn

“And he dwelt there”—This teaches that Jacob our Father did not go down to Egypt to live there permanently but rather to dwell temporary. As the Torah recounts, “They said to Pharaoh, ‘We have come to dwell in the land, for there is no pasture for your servants’ sheep, for the famine is very heavy in Canaan. And now, please let your servants settle in the land of Goshen.’” (Gen. 47:4) – Haggadah

At the bottom level [of poverty] are more than one billion people who live on $1 a day or less… This is life without options…These are families whose children are regularly harvested into slavery…If we compare the level of poverty and the amount of slavery for 193 of the world’s countries, the pattern is obvious. The poorest countries have the highest levels of slavery. – Kevin Bales, Ending Slavery (2007), p. 15-17

Some formerly trafficked persons had never planned to live in the United States…[but for others] migration for work was a mobility strategy, a plan to attain long-term economic goals…In short, this is an ambitious and resourceful group, willing to avail themselves of whatever resources are within their reach. – Denise Brennan, Life Interrupted (2014), p. 15

• Bales and Brennan, both respected researchers, present different views of modern slavery, each of which is supported in the anti-trafficking community. How do you respond to their portrayals?

• Which model better describes the biblical Jacob and his sons?

For most of us, human trafficking is an issue that happens far away, but each year thousands of children are victims of trafficking here in our own country.

We ask, “Why did we not know about this modern day slavery?”

There are few advocates for trafficking victims. Human slaves are, by definition, the most powerless people on Earth. Therefore, each of us has a responsibility to speak out and take action. We must be that voice that screams out against this outrage of human trafficking and demands change. We must try to improve justice for trafficking victims and help curb the demand to eliminate human trafficking forever. By our actions, we can rescue thousands of men, women, and children, giving them back their stolen lives.

For once we know that trafficking exists, we can never be the same. Our failure to speak out makes us complicit in this crime. So on this festival of Passover, when we tell the story of our own journey from slavery to freedom, we must speak out and create a new reality for those who live in slavery today and give them lives of dignity and freedom, just as we celebrate tonight.

– Susan Stern, Chair, President’s Advisory Council on Faith Based and Neighborhood Partnerships

It has been 10 years since I have been free, flying like a bird! In the mid-1970s, at the age of 15, I was sold for $200 to a man who I supposed to be working for…I was kept in his house for more than five years against my will… I spent 22.5 years in prison for this crime I did not commit. After all those years, I thought I was going home with my family. But no! I did not go home. The INS picked me up and held me for 5 months and 7 days. This time I was told I was going to be deported… Human trafficking is like a monster that has a lot of heads. If you catch one trafficker, get rid of one head, there are still many others who continue damaging and causing pain to our society…Let’s advocate and stop the monster from hurting the new generation and others.

– Maria Suarez, who was trafficked within Los Angeles County. More of her story can be found here.

Ten Plagues of Forced Labor

It’s easy to think of the plagues suffered by a person while s/he is enslaved—physical and sexual abuse, stolen wages, fear and humiliation. And it’s easy to imagine the courage it takes to escape, as well as the kindness of strangers that sometimes makes this possible. But even after getting free, troubles mount that may not be immediately apparent. For people who come to the United States from abroad and find themselves enslaved, these plagues continue to follow them long after their escape.

Spill a drop of wine/grape juice for each of the following:

- No belongings[6] People often escape with just the clothes on their back.

- Enforced separation from family [7] Not only during forced labor but during the lengthy application for a T visa. This also affects American citizens who are enslaved within the US.

- Trauma[8] Including nightmares and fear of going to public places lest the person encounter his/her trafficker or someone who knows the trafficker.

- No local support network[9] Imagine being truly on your own, without even a casual acquaintance to turn to.

- Limited English[10] An American citizen who is enslaved at least has this going for her—s/he’s not in a foreign country where she doesn’t understand language or culture. Unless s/he has cognitive challenges, as has been the case in a number of instances of slavery.

- Shame[11] Tragically, this often leads to avoiding the local coethnic community that could be a source of support and to concealing the truth of what happened from their families.

- No government benefits[12] Some benefits become available if the person is in the process of applying for a T visa—but that can be frightening because it requires interacting with police and government bureaucracy, which the person may have learned to mistrust (either from her/his home country or from the trafficker’s threats). Even if a T visa is secured, benefits run out long before the need does.

- No transportation or childcare[13] This makes it difficult to get a job—or makes commuting take so long that night classes become impossible, trapping the person in a dead-end existence.

- Lack of training for police[14] Police lack training in understanding or identifying modern slavery. They may arrest victims as criminals or, chillingly, return them to the home of their traffickers.

- Lack of training for service providers[15] Including homeless shelters. Even with the best of intentions, a trained but not specialized professional can easily miss some of the above.

The rabbis of the Haggadah use midrashic math to multiply the ten plagues into 50, 200, even 250. How might these ten plagues of trafficking grow into even more challenges?

As a rabbinical student in T’ruah’s summer fellowship, I interned with Safe Horizon’s Anti-Trafficking Program. In learning from my colleagues and getting to know some of Safe Horizon’s clients, I came to appreciate the tremendous power of shame. The question is often asked of survivors of trafficking, “Why didn’t you just leave?” One answer: “I was told I owe money, and I can’t bear not paying it back.” Another: “How could I return to my family without the salary I promised I’d share with them?” Or another: “My ‘employer’ had so much psychological control over me, I simply couldn’t imagine getting out.”

Shame keeps men and women in involuntary servitude even when physically they might be able to leave. It silences and stymies them, denying them the dignity and freedom deserved by everyone created in the image of God.

– Rabbi Daniel Kirzane, Temple Beth Chaverim Shir Shalom, Mahwah, NJ

Shortly after the Israelites leave Egypt, God commands a census, which counts 603,550 men fit for military service. (I can only hope that the women, children, and elderly were counted too and simply not reported in the text.)

A census symbolizes more than a statistical or military endeavor; enumerating our population is a prerequisite for living together and governing a community that provides for all. What does a census have to do with slavery? Slaves suffer in part when societies choose to leave them undocumented, uncounted, unidentified, and forgotten.

My work as a population health physician has taught me this: Governments can shed their responsibility for delivering and protecting the freedoms of undocumented and uncounted people by excluding them from censuses and statistics. A nation can appear healthy if the ill are not seen; it can appear wealthy if the poor do not report their income; it can appear literate if the uneducated do not complete a survey; and it can appear free if the slaves are not counted. Counting is the seed of accountability. Truly inclusive statistics can be a tool of resistance.

– Dr. Aaron Orkin, MD, MPH, MSc; University of Toronto; BYFI ‘99

Dayeinu

Dayeinu is a symmetrical song. The first seven lines describe the Exodus, culminating with drowning the Egyptians in the sea. The second seven describe the building of a just and self-sustaining society, culminating with the building of the Temple. Only when the system is stable can we really say “dayeinu.”

In the same way, the work of fighting slavery does not end the moment a slave is freed. In the short term, we must provide for their basic needs, as Dayeinu describes God doing: first basic care, manna, and rest, then on to larger issues. The work continues for years into the future as we help survivors heal and support themselves, and as we build social and economic systems that no longer rely on or allow exploitation.

“If God had gathered us before Mt. Sinai but not given us the Torah, Dayeinu.”

The grand vision of Sinai is not enough; it needs to be fleshed out with the entire body of Torah in all its specifics. Immediately after the Ten Commandments comes parashat Mishpatim, with all the particulars of how to construct a just society. As Dr. Orkin and Judge Safer Espinoza reflect, the goal of ending slavery must be backed up by a mass of details.

As a Jew with whom the themes of freedom and systemic change resonate deeply, I have the opportunity to honor some of our best traditions by serving as director of the Fair Food Standards Council. The Council is charged with monitoring and enforcing the Coalition of Immokalee Workers’ agreements, including a human rights-based Code of Conduct. FFSC does the unglamorous, extremely detailed, yet very beautiful work of ensuring that systemic change is implemented and made real in the fields for the men and women who harvest the food we eat. Exodus from Egypt is a powerful metaphor for the transformation we see on Fair Food Program farms that have put an end to modern-day slavery, sexual assault, physical abuse, wage theft, and dangers to workers’ health and safety. It is a privilege to serve this groundbreaking partnership between workers, growers and buyers as it truly brings about a “new day.”

– Judge Laura Safer Espinoza, Director, Fair Food Standards Council

A rabbi once taught me that Judaism was a “system for goodness.” Over the years, I have learned to recognize that I am a part of systems that are often far less than good; systems that privilege few and hurt many. Our society’s demand for cheap products and services, and my mere participation in modern commerce, implicates me in the cycle of exploitation. It is this recognition that drives me to work to reform our public institutions so that they enable others to enjoy the same freedom that we celebrate around the Seder table.

The ability to rejoice in our freedom carries with it great responsibility, for we cannot truly be free unless all people are free. Let us direct ourselves towards fixing systems that exploit vulnerable members of our communities and bring a time of liberation from these narrow places for all people.

– Keeli Sorensen, Director of National Programs, Polaris Project

Rabban Gamliel Says:

Why is there a tomato on the seder plate? This tomato brings our attention to the oppression and liberation of farmworkers who harvest fruits and vegetables here in the United States. And it reminds us of our power to help create justice.

A tomato purchased in the United States between November and May was most likely picked by a worker in Florida. On this night, we recall the numerous cases of modern slavery and other worker exploitation that occurred in the Florida tomato industry, which centers on the town of Immokalee, as recently as 2010.

But a transformation is underway. Since 1993, the Coalition of Immokalee Workers, a farmworker organization, has been organizing for justice in the fields. Together with students, secular human rights activists, and religious groups like T’ruah: The Rabbinic Call for Human Rights, they have convinced 13 major corporations, such as McDonald’s and Walmart, to join the Fair Food Program, a historic partnership between workers, growers, and corporations. Not only does the Fair Food Program raise the wages of tomato workers, it also requires companies to source tomatoes from growers who agree to a worker-designed code of conduct, which includes zero tolerance for forced labor and sexual harassment.

Today, the tomato fields are “probably the best working environment in American agriculture,” according to Susan L. Marquis, dean of the Pardee RAND Graduate School, a public policy institution in Santa Monica, CA.[16] www.nytimes.com/2014/04/25/business/in-florida-tomato-fields-a-penny-buys-progress.html?_r=0 Since 2011, when more than 90% of Florida’s tomato growers began to implement the agreement, over $14 million has been distributed from participating retailers to workers, and not one new case of slavery was discovered in the Florida tomato fields.

But the resistance of holdout retailers, like major supermarkets and Wendy’s, threatens to undermine these fragile gains, as they provide a market to farms that continue abusive labor practices.

Since 2011, T’ruah has taken more than 50 rabbis to Immokalee to learn from the CIW. The stories they hear – and the transformation they see – inspire them to go home and turn their congregations into more than just educated consumers. They become activists; many of the rabbis whose words grace these pages are #TomatoRabbis. They have become part of the larger movement of Fair Food activists, urging corporations to live up to their professed values and join the new day dawning in the Florida tomato industry that is the only proven slavery-prevention program in the U.S.

A brown and green dream. Every tomato picker holds a bucket. It’s his only tool. Cradling the bucket against his belly, he picks pre-ripe tomatoes, tomato after tomato, green with promise. When the bucket is full, 32 pounds of possibility, he throws the bucket up to the truck… for a moment, defying gravity…

And then the bucket is empty.

He gets a token. Good for fifty cents. And an empty bucket. Start again.

A day of slam-dunking tomatoes into that bucket, his body a human backboard, leaves a human stain. Over every worker’s heart, a deep brown sun, surrounded by a green halo.

It’s our custom to raise up our matzah. The bread of poverty. The bread of oppression. But also the bread of liberation.

The tomato, too, is a dual symbol. It reminds us that slavery persists, today, wherever farm laborers have not tasted the sweet freedom made real by the brave men and women of the CIW. And it celebrates the awesome power of those workers, who refuse to forfeit their humanity, who point the way toward liberation. Not just for themselves. But for all of us.

Let us raise up the tomato on our seder plate.

Let us rouse ourselves to stand in solidarity with all who are exploited bringing food to our tables.

And, in doing so, let us raise up our holy tables in a banquet of liberation, affirming wisdom and courage, wherever they are exiled, in any soul — there, or here.

– Rabbi Michael Rothbaum, Beth Chaim Congregation, Danville, CA

We are meant to feel the sting of the whip on our back.

We have spent 3,000 years closing our eyes, imagining the hopelessness and outrage of working in that mud. We see ourselves as people who know what it is like to be slaves. We are oppressed. We are born into hardship. We, but for the deliverance of God, are helpless against tyranny.

We relive our slavery each year so that the pain, oppression, and struggle of others living it today will feel more immediate to us. We are “chosen” to be the ones who have seen darkness, been delivered into light, and now will deliver others.

So does Passover truly remind you of your freedom? Do you hear the call to “break the chains of the oppressed?” Is this the night you choose to act?

– Robert Beiser, Executive Director, Seattle Against Slavery

We end Maggid with a taste of Hallel, beginning with Psalm 113. The first line sums up all of Maggid in four words:

הַלְלוּיָהּ הַלְלוּ עַבְדֵי ה׳ |

Halleluyah hallelu avdei Adonai Praise God, you slaves of God! |

This recalls God’s declaration towards the end of Leviticus (25:42)…

כִּי עֲבָדַי הֵם אֲשֶׁר הוֹצֵאתִי אֹתָם מֵאֶרֶץ מִצְרָיִם; לֹא יִמָּכְרוּ מִמְכֶּרֶת עָבֶד. |

For they are My slaves, whom I brought out of the land of Egypt—they shall not be sold as slaves. |

…as well as the line by Yehudah HaLevi, the 12th century philosopher and poet:

עַבְדֵי זְמָן עַבְדֵי עֲבָדִים הֵם עֶבֶד ה’ הוּא לְבַד חָפְשִׁי. |

Slaves of time are slaves to slaves. Only a slave of God is free. |

Consider singing the first line of Psalm 113 or this popular line from Psalm 100:2: Ivdu et Hashem besimcha, bo’u lefanav bir’nana (Serve God with joy, come before God with song). Ethiopian-Israeli singer Etti Ankri has also set HaLevi’s poem to music: www.youtube.com/watch?v=FtrYCyfFXTs

We conclude Maggid by blessing and drinking the second cup.

“In every generation a person must see him/herself as if s/he came out of Egypt…Therefore we are obligated…”

This is the seder’s fulcrum, the turning point the leverages our collective memories of slavery and turns them into collective obligation. This is the moment when we return to Ha Lachma Anya and say:

הָשַׁתָא עַבְדֵי לַשָׁנָה הַבָּאָה !בְּנֵי חוֹרִין |

Hashta avdei Leshanah haba’a b’nei horin! Now – slaves. |

It is not enough simply to remember, or even to retell the story of the Exodus from Egypt. Rather, the Haggadah demands, “in each generation, each person is obligated to see himself or herself [lir’ot et atzmo] as though he or she personally came forth from Egypt.”

The text of the Haggadah used in many Sephardic communities demands even more. There, the text asks us “l’har’ot et atzmo” –

to show oneself as having come forth from Egypt. The difference of a single Hebrew letter changes the obligation from one of memory to one of action.Showing ourselves as having come out of slavery demands that we act in such a way as to show that we understand both the oppression of slavery and the joy and dignity of liberation. Our own retelling of the narrative of slavery pushes us toward taking public action to end slavery in our time.

– Rabbi Jill Jacobs, Executive Director, T’ruah

מוֹצִיא מַצָּה Motzi Matzah

[17] There is a custom not to eat matzah in the weeks before Pesach, so that the taste is fresh at the seder. If your community seder is being held before the holiday, options include using egg matzah, crackers such as Tam-Tams, or having matzah present as a symbol but not eating it. Similarly, the blessings for eating matzah and maror should only be said on Pesach itself, since that is when the commandment applies.

Hamotzi thanks God for bringing bread from the earth. This bread results from a partnership between God and humanity: God provides the raw materials and people harvest, grind, and bake. So too must we remember that combating human trafficking requires partnerships: among survivors, allies, lawyers, social workers, law enforcement, diplomats, people of faith…the circles of involvement are ever-expanding.

בָּרוּךְ אַתָּה ה’ אֱלֹהֵינוּ מֶלֶך הָעוֹלָם הַמּוֹצִיא לֶחֶם מִן הָאָרֶץ. |

Baruch Atah Adonai, Eloheinu Melech ha’olam, hamotzi lechem min ha’aretz. Blessed are You ETERNAL our God, Master of time and space, who brings forth bread from the earth. |

רָחְצָה Rachtzah

Our hands were touched by this water earlier during tonight’s seder, but this time is different. This is a deeper step than that. This act of washing our hands is accompanied by a blessing, for in this moment we feel our People’s story more viscerally, having just retold it during Maggid. Now, having re-experienced the majesty of the Jewish journey from degradation to dignity, we raise our hands in holiness, remembering once again that our liberation is bound up in everyone else’s. Each step we take together with others towards liberation is blessing, and so we recite:

– Rabbi Menachem Creditor, Congregation Netivot Shalom, Berkeley, CA

בָּרוּךְ אַתָּה ה’ אֱלֹהֵינוּ מֶלֶך הָעוֹלָם אֲשֶׁר קִדְּשָׁנוּ בְּמִצְוֺתָיו וְצִוָּנוּ עַל נְטִילַת יָדָיִּם. |

Baruch Atah Adonai, Eloheinu Melech ha’olam, asher kidshanu bemitzvotav vetzivanu al netilat yadayim. Blessed are You ETERNAL our God, Master of time and space, who has sanctified us with commandments and instructed us regarding lifting up our hands. |

“We Are Not Tractors”

Banner, signed by members of the CIW, 1998. Created in response to an Immokalee tomato grower who said, “The tractor doesn’t tell a farmer how to run a farm.”The taste of bitterness reminds us that we were once slaves; that slavery still exists. In Immokalee, Florida, I saw the evidence of the bitterness of slavery: I saw the chains in the Modern Slavery Museum organized by the CIW; I spoke with farmworkers who had gotten up at 4am every morning to wait for hours in a parking lot, hoping for a few hours of work, doubtful whether they’d ever get paid. Bitterness reminds us, and its sharp flavor can wake us up. In Immokalee, I saw the amazing action that the taste of bitterness can inspire: weekly meetings of workers to plan their own liberation; marches on foot, on bicycle, to protest at corporate headquarters; immigrant workers who lack all legal protections creating a powerful mechanism to stop the abuses they once faced. As we bless this maror, let us bless both awareness and awakeness—the knowledge of bitterness, and of the action it can inspire us to take.

– Rabbi Toba Spitzer, Congregation Dorshei Tzedek, Newton, MA

מָרוֹר Maror

As we eat bitter herbs, we reflect on the bitterness of slavery through the testimonies of survivors.

“When you’re there, [enslaved,] you feel like the world is ending. You feel absolutely horrible…Once you’re back here on the outside, it’s hard to explain. Everything’s different now. It was like coming out of the darkness into the light. Just imagine if you were reborn. That’s what it’s like.” – Adam Garcia Orozco, farmworker

“I was so tired and did not know how I could continue working like this. But I did not say anything to anyone. I did not know how I could do what was expected…All the time I was crying. Even sometimes at night I could not sleep. I would cry so hard I would have a headache. I would dream and see my family. It was a very hard time.” – Elsa, domestic worker (Life Interrupted, p. 90, 92)

I remember when he lifted up his shirt and I saw that scar. It was the first time I had ever seen a scar like that—it ran about 8 inches in length down the side of his body. It was unbearable to see. I had worked with sex workers in Guatemala, some of whom had been sex trafficked, and with refugees from East Africa in Israel, some of whom had been sex or labor trafficked, but I had not encountered organ trafficking in a real way before. This young Eritrean teenager had somehow survived and had made it to Tel Aviv. His scar was thick and frightening. His kidney was gone. I could feel the trauma he had endured and it seeped into me. I couldn’t sleep for nights after that moment. This is a type of human trafficking we often forget and overlook, but it is real, it is happening throughout the world, it is inhumane, and it must be stopped.

– Maya Paley, Director of Legislative and Community Engagement, National Council of Jewish Women/Los Angeles

כּוֹרֵך Korech

In Korech, we combine bitter maror with sweet charoset in a single mouthful. This makes real for us the dual realities of trafficking survivors, who celebrate their freedom and move forward with their lives while fighting an uphill battle against trauma and poverty. As you enjoy your sandwich, consider these diverse reflections of trafficking survivors.

“I wish the police could find him. I wish that I could send him to jail because he really destroyed me. He took a lot of time from me. But I don’t feel like I live with this; I don’t bring my past with me now…There is justice here [in America]. It’s fair here. I feel strong because I now know when I can say no and when I can say yes. I have choices.” – Anonymous, forced into sexual labor (Life Interrupted, p. 148)

“It’s hard juggling it all, but if I don’t do something, I have to think about what happened to me. So if I am in school and busy, I don’t think about it too much.” – Julia (ibid., p. 166)

“I wanted to forget everything. I wanted to do something in my life. I suffered a lot…[My abuser] told me I would never learn English. He told me, ‘You think you are going to learn in just a couple of years?’ And I did and proved him wrong…I [crossed the US-Mexican border] by myself. It took three days with no water. I tell myself now that I am not doing that for nothing.” – Gladys, domestic worker (ibid., p. 167)

“I think there is a lot of work to do. When I go to a conference [on trafficking] I learn a lot, and I see that there is so much ahead of us. I learn from other activists, especially the ones at the Coalition of Immokalee Workers. They really listen to workers. We have a lot in common. We all have a lot of work to do.” – Esperanza (ibid., p. 174)

“In the beginning, you often think you are wasting your time. But if you take it step by step, you can do it. It looks really hard and really big. But [newly escaped people] will get help from the program—they don’t have to do it alone…I was one of them before; I know how they think…They have a fear of making mistakes. It’s hard to say yes again. Some want to do things almost perfectly. But of course they may make the wrong decisions!” – Eva (ibid., p. 175)

Can you imagine the Passover story if, rather than having figures like Moses and Miriam as our guides, it was told from the perspective of Pharaoh? Probably not. But what if it was told from the perspective of a well-intentioned Egyptian, who, though he stood to benefit from the privileges of his position, took pity upon the slaves?

Part of the power of the Israelites’ journey from slavery to liberation lies in the fact that the struggle for freedom was led by slaves themselves — and the telling and retelling of that journey was thus theirs to craft. How often do we hear today’s stories of injustice told from the perspective of a savior? How often do we hear them told by those who experienced those injustices, strategized and worked to counter them, and ultimately forged their own liberation?

As we listen for today’s stories of communities breaking from today’s bondages, let us seek out the struggles led by those most directly affected by an injustice. And if the telling and retelling of those stories sounds foreign to our ears, let us rejoice in knowing that their stories are theirs alone to craft, and ours to hear, to seek to understand, and to engage.

– Elena Stein, Faith Organizer, Alliance for Fair Food

Who better to inform public policy than the people it impacts the most?

As awareness about human trafficking continues to grow, survivor voices need to be prioritized. Many groups, including concerned citizens, non-profits, and government agencies are stepping up to address this atrocity. Central to the success of these groups is the input of survivors.

Survivors are capable of informing policy, shaping programmatic and funding decisions, providing training and technical assistance, and leading educational efforts.

Survivor input will also improve the likelihood that proposed plans and solutions will work. We know what has worked (e.g., having other survivors to relate to) and what hasn’t worked (e.g., inflexible shelter rules or social services protocols that don’t take survivors’ needs into account).

Survivors are increasingly engaging in anti-slavery work. The role of survivors is critical to our collective learning about human trafficking and the development of public policy to effectively address modern day slavery in a comprehensive way.

– Ima Matul, Survivor Organizer, Coalition to Abolish Slavery and Trafficking (CAST); National Survivor Network

“Aquatic Rhapsody,” by Claudia Cojocaru

38” by 46”, Acrylic on canvas“Surviving is like walking a tightrope above the abyss, one wrong move and you fall… I fell many times, and I fell hard. It hurt, it bruised, it felt numbing and alone, but it never felt like I needed salvation. I am my own salvation, and I am walking my own tightrope above the abyss we all share. I see others walking theirs… They see me too. We are all survivors of something, but we move on, leaving the past behind, to make the best of our future.

If we linger in a place too long, we do not grow, we may regress and even fall, for the tightrope is just that, a rope, and it may break under the weight of assigned identities and labels.

Yes, I am a survivor of forced sex work, but I am not only that. My identity is fluid, and it moves on, perpetually morphing into who I am evolving into everyday. My name is Claudia Cojocaru, I was once hurt, lost and alone, but it is not who I am anymore. I am an activist for justice, equal rights, respect and recognition of agency and women’s choices. I am an artist, a researcher, and a tightrope walker.”

- How do these quotes support or challenge assumptions you hold about people who survive trafficking?

What questions would you want to ask these people if you met one of them?

צָפוּן Tzafun

Tzafun, which literally means “hidden,” is the part of the seder where we seek what is not obvious, when we look for something other than what is in front of our faces. It is also when we return to that which was broken earlier in the evening and try to make it whole again. In this way, Tzafun serves as the organizing principle of the second half of our seder, where we ask ourselves what world we want to see. Then we commit ourselves to making it real.

צָפוּן ← צָפוֹן

By moving one little dot, Tzafun becomes Tzafon, North. What North Star will guide your work to bring about the world you want to see?

It’s no accident that one of the leading national anti-trafficking organizations is named Polaris, after the North Star.

שֻׁלְחָן עוֹרֵךְ Shulchan Orech

As we enjoy our Pesach meal, we thank all of the people who labored to bring this food to our table, from the workers who planted our food to the people who served it.

- How many different roles can you think of in this chain of food production?

Over dinner, turn to someone near you and ask each other how your values affect your buying choices.

CIW member Gerardo Reyes Chavez reflects, “Why do I spend every day harvesting food for the rest of America and then have to wait in line at a food pantry on Thanksgiving for a plate of food?” How would you respond? How can we change this reality?

There are three movies that have affected me so deeply that I couldn’t move afterwards, their impact so deep that a new journey opened up. One was “The Dark Side of Chocolate,” which I saw in Fall 2010. It documents the role of trafficked child labor in the cocoa fields in the Ivory Coast, where half our chocolate comes from. I was stunned to learn that this most delicious and heavenly food was being produced by slave labor! Two things were immediately obvious: the connection to a contemporary Pesach story and the fact that there was no chocolate we could eat on Passover that wasn’t probably tainted by child labor. Sitting there after the movie, I decided to launch “The Bean of Affliction Campaign” through Fair Trade Judaica. After two years, a rabbinic ruling identified the first fair trade and Kosher for Passover chocolate product, which is now widely available through the Jewish Fair Trade Partnership with T’ruah and Equal Exchange.

The Conservative Movement recognizes many varieties of Equal Exchange dark chocolate as kosher for Passover if purchased before the start of the holiday. For more information, visit here.

– Ilana Schatz, Founder, Fair Trade Judaica

In the third paragraph of Birkat haMazon (Rachem…), we appeal to God for our most basic needs—sustenance and shelter. We pray,

ונָא אַל-תַּצְרִיכֵנו ה’ האֱלֹהֵינוּ לֹא לִידֵי מַתְּנַת בָּשָׂר וָדָם וְלֹא לִידֵי הַלְוָאָתָם. |

Please do not make us depend, Adonai our God, on the gifts of flesh and blood or their loans. |

While in context this means gifts or loans from other people, it could also be understood more literally as actual “loans” of flesh and blood, such as take place in prostitution and

forced labor. This reading cuts to the core of Rachem’s concluding plea, “שֶׁלֹּא נֵבוֹשׁ וְלֹא נִכָּלֵם לְעוֹלָם וָעֶד” “that we should never suffer embarrassment nor humiliation.” This is, at base, what we all desire: a life of dignity. Unfortunately, the threat of becoming a gift of flesh and blood looms as largely today all over the world as it did for our ancestors.

– Raysh Weiss, PhD, JTS Rabbinical School class of 2016; T’ruah board member and summer fellowship alumna; BYFI ‘01

- Why might a shepherd be inclined to say a simpler, shorter form of this blessing?

Later authorities added the phrase “Sovereign of the World” to Benjamin’s original prayer. In the context of slavery and freedom, why does it matter that every blessing remind us that God is the ultimate Sovereign? How does our sense of the sacred or the Divine inspire our actions to build a world of ḥesed, lovingkindness?

Bless and drink the third cup.

בָּרֵךְ Barech

Pour the third cup. (Those wishing to say the full birkat hamazon can find its text easily in whatever siddur or bentsher is handy.)

בריך רחמנא מלכא דעלמא מריה דהאי פיתא |

Brich rachamana malka d’alma marei d’hai pita. Blessed is the Merciful One, Sovereign of the world, Master of this bread. |

This one-line Aramaic blessing can be used as a shorthand form of birkat hamazon under less-than-ideal circumstances (b’di avad). It has its origins in this Talmudic discussion about the shortest text that fulfills one’s obligation to say a blessing after eating (Brachot 40b):

בנימין רעיא כרך ריפתא ואמר בריך מריה דהאי פיתא אמר רב יצא והאמר רב כל ברכה שאין בה הזכרת השם אינה ברכה דאמר בריך רחמנא מריה דהאי פיתא |

Benjamin the shepherd made a sandwich and said, “Blessed is the Master of this bread.” Rav said he fulfilled his obligation. [Really?] But hasn’t Rav said, “Any blessing which does not mention the divine name is not a blessing”? Rather, [Benjamin] said, “Blessed is the Merciful One, Master of this bread.” |

An early morning conversation with my daughter, Lila Rose, age 3 ½:

LR: Why has Elijah not come to our house, Mama?

Me: Elijah is going to come when it is time for a new world to come.

LR: I think we should give Elijah a present when Elijah comes.

Me: What should that be?

LR: Juice.

Me: Ok.

LR: But Elijah is going to be carrying her babies so how is she going to get the juice? Oh! I know, she can carry her babies in a sling and then she can drink the juice and bring a new world.

May she come soon with her babies.

May he come soon surrounded by elders.

May zhe bring us all along.

And may we work to make that day happen with open hearts, committed hands, and a willing spirit.– Rabbi Susan Goldberg, Wiltshire Boulevard Temple, Los Angeles, CA

אֵלִיָּהוּ הַנָּבִיא אֵלִיָּהוּ הַתִּשְׁבִּי אֵלִיָּהוּ הַגִּלְעָדִי בִּמְהֵרָה בְיָמֵינוּ יָבֹא אֵלֵינוּ עִם מָשׁיחַ בֶּן דָּוִד. |

Eliyahu ha-navi, Eliahu ha-Tishbi, Eliahu ha-Giladi. Bim’hera veyameinu yavo eleinu im mashiach ben David. Elijah the prophet, Elijah the Tishbite, Elijah the Gileadite. |

- Invite all of the seder guests to walk together to the door, to let Elijah in. What do you see when you look out at the world?

When you open the door from this position of struggle (see comment on next page), whom might you invite in? Whom do you reach out to?

Opening the Door for Elijah

Miriam the prophetess is linked with water in a number of ways. She watched over her baby brother Moses in the Nile and sang and danced at the shores of the Reed Sea. Midrash teaches us that when Miriam died, the magical, portable well that had sustained our people dried up.

According to tradition, Elijah will bring Messiah to us and the world will be redeemed. In my lyrics (below), Miriam brings us to the waters of redemption. It will then be our task to enter the waters and together redeem the world.

Instead of pouring out wrath, let us pour forth love, forgiveness and peace – for the soothing and healing of our broken world.

– Rabbi Leila Gal Berner

מִרְיָם הַנְּבִיאָה עֹז וְזִמְרָה בְּיָדָהּ מִרְיָם תִרְקֹוֹד אִתָּנוּ לְהַגְדִּיל זִמְרַת עוֹלָם מִרְיָם תִרְקֹוֹד אִתָּנוּ .לְתַקֵּן אֶת הָעוֹלָם בִּמְהֵרָה בְיָמֵינוּ הִיא תְּבִיאֵנו אֶל מֵי הַיְּשׁוּעָה. |

Miriam ha-neviah, oz v’zimra beyada, Miriam tirkod itanu lehagdil zimrat olam, Miriam tirkod itanu letaken et ha-olam. Bim’hera veyameinu hi tevi’einu el mei ha-yeshua. Miriam, the prophet, strength and |

During my trip to Immokalee, I heard many stories from workers who described the conditions before and after the Fair Food Program. One in particular stands out: “Rosalie” told of an experience of sexual harassment on a farm by a supervisor. This person showed up at her home and threatened her in front of her children and friends.

Because she was working on a farm that participated in the Fair Food Program, she could report the perpetrator to the Fair Foods Council. Within hours, the supervisor was fired and her workplace was safe again. Rosalie’s story reminds me of both the vulnerability of workers in exploitative conditions and of the power of organizing to change those slave-like conditions.

As we lift up Miriam’s cup, a symbol of healing and redemption, let us call out for justice and for change so that all women, and all people, can be afforded dignity and protection in their work.

– Rabbi Laura Grabelle Hermann, Kol Tzedek, Philadelphia, PA

RABBIS IN ACTION

After my summer fellowship with T’ruah, I stayed involved with Damayan, the domestic workers’ organization where I had interned. I helped them plan a rally at the Philippines consulate in New York, where they were trying to pressure the Philippines’ government to provide more support for Filipino/as who had been trafficked, and I wrote an Op-Ed to draw the attention of the Jewish press.

It was a humbling and inspiring experience to join with these workers, who not only overcame their own challenging work environments but went on to organize, empower, and protect fellow domestic workers.

I was honored to partner with Damayan, a worker-run organization of smart, powerful, and capable individuals, and to think about how I, in my role as Jewish clergy, could best move the Jewish community to support their anti-trafficking work.

– Avi Strausberg, Rabbinical School of Hebrew College Class of 2015, T’ruah summer fellowship alumna

Shfoch Chamat’cha

The authors of the seder chose this moment to express their anger at the dangerous anti-Semitic world they lived in. While such anger may need a new target today, that does not mean it has no place at the table. Rabbi Mishael Zion, Co-Director of the Bronfman Youth Fellowships in Israel, teaches that the seder’s two door-openings are fundamentally opposites. When we opened the door at Ha Lachma Anya, we focused on local injustice; we, from our position of privilege, are the ones capable of feeding those who are hungry. Here, late in the seder, we open ourselves up to the massive injustices that affect the entire world. We give ourselves permission to name our anger at the fact that slavery still exists in the 21st century, to recognize our limitations, and to cry out, asking God to show up as an avenger of injustice. In the words of Psalm 94, the Psalm for Wednesday:

אֵל נְקָמוֹת ה’ אֵל נְקָמוֹת הוֹפִיעַ! |

God of vengeance, Adonai; God of vengeance, appear! |

The world we want to see will have no need of our righteous indignation, but until that world is here, we cannot afford to ignore those darker feelings.

“The phrase ‘working with not for survivors of slavery’ continued to play through my thoughts as I was creating this piece. When all the little oceans in a drop come to work with each other, what an impact we can make.” Margeaux is a survivor of domestic child sex trafficking. Much of her artwork incorporates everyday items that other people might consider trash. This serves as a symbol that people whom our society might be ready to discard—among them people forced into human trafficking—remain creatures of value and beauty. Margeaux has transcended her experience as a trafficking victim, and today she is an advocate, motivational speaker, and artist. Visit her website.

Psalm 89:3

Music and English lyrics written by Rabbi Menachem Creditor after 9/11

A world of love will be built. (Psalm 89:3)

I will build this world from love…yai dai dai…

And you must build this world from love…yai dai dai…

And if we build this world from love…yai dai dai…

Then God will build this world from love…yai dai dai…

Listen:

Kol HaOlam Kulo

Hebrew based on Rebbe Nachman of Breslov, Likutei Moharan 48

כָּל הָעוֹלָם כֻּלוּ גֶשֶׁר צַר מְּאֹד וְהָעִיקָר לאֹ לְפַחֵד כְּלַל. |

Kol haolam kulo gesher tzar me’od Veha’ikar lo lefached clal. The whole entire world |

עוֹלָם חֶסֶד יִבָּנֶה. Olam ḥesed yibaneh.

הַלֵּל Hallel

Fill the fourth cup and celebrate the world you want to see with songs that have sustained activists in the past and today—we’ve included a few of these songs, but feel free also to sing other songs that give you the strength to move forward. Follow the links for online recordings, where available.

Psalm 118:25

Listen:

Please God save us!

South African Folk Song

Zulu (original):

Siyahamba ekukhanyeni kwenkhos’.

We are marching in the light of God.

Listen:

אָנָּא ה’ה הוֹשִׁיעָה נָּא ה אָנוּ צוֹעָדִים לְאוֹר ה’ה |

Ana Adonai Hoshia Nah Anu tzo-adim l’or Hashem. |

We may tell our story and utter our prayers on this Passover night, but something transformative happens when we sing. Song transports us from despair to courage. From hopelessness to joy. From slavery to freedom. If you can sing a Hallel psalm of gratitude, of hope, even of despair, you know your soul is still alive.

Men were the priests and leaders of ancient ritual. But women were the songleaders of our people: beginning with Miriam, who led the women in singing and dancing as we crossed the sea. Without time to bake bread, she instructed the women to pack their timbrels as they left slavery behind. They didn’t know what they future held, but the Israelites were preparing to sing, knowing that song would help them recognize when they were truly free.

– Rabbi Angela W. Buchdahl, Central Synagogue, New York, NY; BYFI ‘89

Im Ein Ani Li, Mi Li