[No.] 8. Don’t steal content; share.

For Jews living in accordance with halachah—and law-abiding Americans—there’s no ambiguity when it comes to illegally downloading music, movies, software, books or any other intellectual property.

“Because business ethics are among the most central legal obligations of Judaism in all the Torah,” said Rabbi Dov Fischer of Young Israel of Orange County, “there is just no way that a person can identify as a practicing religious Jew while actively or regularly downloading or sharing protected intellectual property without paying the required fees.”

But if social media pose a challenge to those who wish to protect their work, new technologies also present opportunities for unique projects that could not have been imagined a generation ago. The Open Siddur Project, for instance, allows individuals to craft their own personalized prayer books from texts that have been uploaded to their site, which includes texts that are in the public domain (like the prayers said by Jews living in the Byzantine empire) as well as prayers written by ordinary individuals who choose to share them.

“The golden rule here is that when people share Torah,” said Aharon N. Varady, founder and director of the Open Siddur Project, “Torah is increased in the world.”

In my interview with Jonah, I explained to him the teaching of the Sfas Emes, the Gerrer Rebbe Yehudah Aryeh Leib Alter, who taught in his drash on parshat Terumah, the following.[1] Translation is Rabbi Arthur Green’s from The Language of Truth: The Torah Commentary of Sefat Emet (JPS 1998, p.121, copyright all rights reserved, and here quoted through Fair Use.

The Midrash Tanhuma quotes: “I have given you good lekaḥ (teaching)” (Proverbs 4:2). [Lekaḥ can also refer to something acquired by purchase.] It then offers a parable of two merchants, one who has silk and the other peppers. Once they exchange their goods, each is again deprived of that which the other has. But if there are two scholars, one who has mastered the Order of Seeds and the other who knows the Order of Festivals, once they teach each other, each has both orders.

The point is that each one of Israel has a particular portion within Torah, yet it is also Torah that joins all our souls together. That is why Torah is called “perfect, restoring the soul” (Psalms 19:8). We become one through the power of Torah; it is “an inheritance of the assembly of Yaakov” (Deuteronomy 33:4). We receive from one another the distinctive viewpoint that belongs to each of us.

Of this, Scripture says: “God gives strength [=Torah] to His people, God bless His people with peace” (Psalm 29:11). The blessed Holy One’s name is “peace”; God is called the King of Peace, who makes peace in the heights. Torah, too, is composed of names of God and that is why Torah leads us to peace. So, too, it says: “He calls them all by name” (Isaiah 40:26), for the name of God includes all the hosts of heaven, joined together by that name. So, too, are the souls of Israel joined together by Torah.

The same was true in the building of the tabernacle. Each one gave his own offering, but they were all joined together by the tabernacle, until they became one. Only then did they merit Shekhinah‘s presence.

This oneness has to exist on the three planes of thought, word, and deed. The tabernacle and Temple represent oneness in deed, Torah stands for unity of word, and God is the One of thought or contemplation.

The word nefesh, used for the “seventy souls” [who went into Egypt], appears to be singular. They all worshiped the same God, had the same longing and desire in their hearts. All of them were turned to God, and thus they became a single nation.

The Open Siddur Project envisions Jewish spirituality as a shared and collaborative project that is rooted in the wisdom of our traditions and which finds expression through the evolving diversity of our communities and the intimate experiences of our individual relationships. Much like the mishkan, the traveling tent of meeting (or tabernacle) was the focal point for those creatively inspired Israelites to share their work, כֹּל אֲשֶׁר נְשָׂאוֹ לִבּוֹ, as their hearts were stirred (Exodus 36:2), so too we see the Open Siddur Project as a kind of יִחוּד, a unification of holy כַּוָּנוֹת (intentions) for those sharing their חִדּוּשִׁים (innovations) in Jewish spiritual practice, in sacred liturgy, in meditations and exercises, and in understanding through translations and commentary. In an age when our עֲבוֹדָה avodah (intentional practice) is expressed by communities and individuals in a multiplicity of ways, it behooves us to take our avodah seriously, respect and reflect this diversity, and provide the means for crafting newly designed סִידּוּרִים Siddurim accordingly. The Open Siddur Project is a community, space, and licensing framework for sharing those designs and enrich our individual and communal avodah with each others’ creativity and insight.

Notes

| 1 | Translation is Rabbi Arthur Green’s from The Language of Truth: The Torah Commentary of Sefat Emet (JPS 1998, p.121, copyright all rights reserved, and here quoted through Fair Use. |

|---|

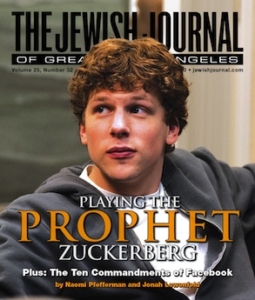

“📰 “Ten Commandments of Jewish Social Networking” (Jonah Lowenfeld, Jewish Journal of Greater Los Angeles 2010)” is shared through the Open Siddur Project with a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International copyleft license.

Comments, Corrections, and Queries