The following Remarks on Family Prayer were written about twelve years ago [ca. 1840] by my beloved daughter, at the request of, and expressly for, Mrs. Belinfante, who wished to have some prayers suited to the capacity of very young children, short and simple. Having been considered valuable by several friends, I now publish them for the benefit of those young mothers who are desirous of beginning at a very early age the religious education of their children. —Sarah Aguilar[1] This introduction to the essay appears only in the UK edition.

| Contribute a translation | Source (English) |

|---|---|

Thoughts on Family Prayer. | |

“It shall come to pass, before they call I will answer, and while they are yet speaking I will hear.” (Isaiah 65:24) “The eyes of the Lord run to and fro throughout the whole earth, “Call upon me in the days of trouble: “The Lord is thy keeper.” (Psalms 121:5) “Leave thy fatherless children: I will preserve them alive, “Whom the Lord loveth he correcteth, “The Lord is nigh to a broken heart, “As one whom his mother comforteth, | |

The following simple prayers are not intended for children to repeat themselves, but to be read by the father, mother, or instructress of a young family, in the presence of all their children, from three years old upwards; earlier if the disposition of the child be such as to allow it to remain attentive during the time the prayer may last. To depend upon a young child reading or repeating a prayer by himself, we must either lose a great deal of valuable time, or dishonour the name of our Father in Heaven, by hearing it constantly and irreverently repeated as a task and lesson, before the infant lips are aware of the deep solemnity, the vital consequence of what they are saying. And the habit of carelessly uttering that Holy name is not lost, even when riper years should make them conscious of the evil habit. | |

It appears to me of the utmost consequence, to impress the infant mind as early as possible with notions of veneration and love for their Father who is in Heaven; and this is easily and delightfully accomplished by their ever associating their parents with their prayers. Imitation is the quality almost the first discernible in children; the love and confidence they bear towards their parents (young children for a mother particularly) urges them to imitate all she does; even to imbibe her feelings of love, or the contrary, wherever they are visible. To make, then, prayers a never-failing source of comfort, of guidance, of relief, let them listen to their mother’s voice, as morning and evening she addresses her Father in Heaven to thank Him for His care — to implore His protection and guidance through the day and night, His forgiveness of their sins. His grace and strength to resist them, and to love Him according to His commandment; and the youngest child will learn to reverence and love the invisible, yet ever-present God. To look upon Him as his Father and Friend, to feel that he owes all his infant joys to Him, he will learn this, before he is conscious of the blessed gain he has imbibed; and in after years, when the full extent of the comfort, the strength, that religion gives, is felt, how will he bless his mother, at whose knee he first learned to address her God, now he feels to his heart’s core, his own! But this will never be obtained so completely if a mother merely hears her child repeat his prayers — unless he has joined her in prayer, or seen her pray, all her instructions will be comparatively of little avail. We cannot expect a young child to feel love and reverence for an unseen Being, of himself — he must do so first, because his mother does, or because he knows all that she does it is right for him to follow. He has heard her utter with solemn reverence the name of God; he has seen her serious and quiet whenever she addressed Him in prayer; that all trifling play or amusement is put away before she begins to pray: and that holy impression will seldom leave the intelligent child through life; it remains even when the parent may have sought the God she has loved and served; remains to hallow her memory, and urge him on to tread the path she trod. | |

Another advantage of this plan is, that a much younger child may be admitted to family prayer than can possibly be taught to pray himself. It is of little consequence that at first he may not quite understand all that his mother reads; he sees her serious yet happy, his brothers and sisters attentive and quiet, and he will learn to be the same, and by imperceptible degrees fully understand and appreciate the privilege of being admitted, though so young, to pray to his Father in Heaven. | |

If it be, as it undoubtedly is, necessary that boys should early learn the comfort and blessedness of prayer, it is doubly more so for girls; and for them how much may maternal affection do? How few women are exempt from sorrow and suffering, either bodily or mental, that may only be soothed by constant and faithful prayer? How few young, gentle hearts pass through life unscathed by those inward sorrows, which can be healed only by the consciousness that the love borne towards us by our Father in Heaven, is deeper, stronger than the dearest felt for us by our friends on earth; and how can we learn this love but by studying His word? and how seek Him in our troubles but by being used in our infancy to address Him in every sorrow, and praise Him for every childish joy? It is the want of this constant intercourse with our Heavenly Father that brings down on the Jewish nation the charge of possessing no comfort in their religion; but it is not our religion that is at fault; it is that we never pray with our children, never permit them to see in ourselves the privilege of prayer, but, contented with desiring them to repeat a set form, rest quite satisfied that they will acquire of themselves all that is needed in religion. This is the reason why many of our nation, yearning for comfort, for the privilege of closer communion with our God, desert their fathers’ faith, and seek” that, so many of whose members show forth so beautifully, so blessedly, its solace and its peace. Oh! should not every Jewish mother tremble, when she thinks that this may be, nay, will be, unless she teach her children to pray, to love their Father who is in Heaven, to revere and feel the privilege, the comfort of His word? and how can she do this but by calling them round her to listen to the morning and the evening prayer? but by evincing how she loves to address her God, and read His word? how careful she is to obey His law, and take His given word for her guide and support in the daily events of life? by showing how earnest she is to lead her children in His paths? Will a child ever forget such lessons? Oh, no! Even in moments of temptation, of doubtful enjoyments, the thought of his mother will be there to check and to save him from evil and from sin. Incumbent as the duty of religious instruction is on mothers of every faith and every class, it is still more imperatively demanded from the mothers of Israel; for they have no assistance in their arduous task, save that which will be vouchsafed them from Heaven, whenever it is sought by earnest and lowly prayer. It rests with them to open to their children the fountains of salvation, of life, of the deep, measureless love, which the history of God’s dealing with His rebellious people can so abundantly, so eloquently prove. Ever turning from His paths, still His mercy failed not; still we are the objects of His love, His tender pity, which “waits to be gracious” only till the heart is lifted up to Him in child-like faith, in earnest prayer. | |

It appears to me that the great fault shown by the Jewish nation, is in puffing up our hearts with pride from the first moment that we can understand that our religion is different from that of those around us. We are told that we alone are of the true religion, that we alone are worthy in the sight of God, that all else is idolatry and folly. Instead of which we should engrave on the yielding hearts of our children the tale of Israel’s awful sin; that we were indeed the favoured of the Lord, the blessed, the loved above all others — but that we rejected His gracious love, we revolted from His merciful yoke, and so awfully and ungratefully sinned, that He was compelled in justice to chastise, and that we are now, even now, suffering from the consequence of those sins. | |

Will not any right feeling child melt at this tale of boundless love and base ingratitude, and feel that he would not act thus, that he would try and love that merciful Being who so much loved him? and then is the moment to impress the still acting mercy of his Father in Heaven upon his little heart. Then tell him we must not despond; that we are God’s chosen people still, though at present under his displeasure; that He loves and cares for us still as His beloved children, and that we should leave no effort untried to serve and love Him that we might prove to Him the sins of our ancestors are not ours, and to show that a religion so pure, so consoling, so full of hope as that we practise, could have its foundation but in God alone. If the Jewish religion were taught thus, would it not be productive of more real comfort, gratitude, faith, and love than it is, alas! too generally now? I seem to have wandered far from the original subject of these few remarks, but it was necessary to evince the great consequence of family prayer. | |

Let it not be thought I would banish from family circles the prayer books so long in use among us; far from it. Both the morning and evening prayers here written, are invariably followed by the Shemang, without which, in my opinion, no form of Jewish prayer is complete; but my great wish was to write a family prayer that would touch the heart, and reach the understanding of the youngest child. This a selection from our prayers could not do of itself; we could not select a portion sufficiently brief for the purpose, and yet to contain the supplication we require; we should never weary the attention of a child, particularly in the solemn duty of prayer. Until the age of seven, I should say, the morning prayer and the Shemang were quite sufficient, followed as they ever should be in the morning by either a few verses or a chapter from the Bible, and a selection of appropriate verses from the Psalms. From seven till nine, we might add the two prayers directly following the Shemang: “And it shall come to pass,” &c.: “And the Lord spake unto Moses,” &c. At nine the Amidah might gradually be added till the whole is said, and at thirteen the inclination of the child might be consulted, whether to read more in the prayer book, or study the word of God rather longer by himself. | |

The evening prayer, the Shemang, a simple hymn, and some well selected verses of the Psalms, is quite enough for any child till the age of thirteen. At that age, if the mother’s duty has indeed been performed, there will be no need to tell a child to pray, or desire it to read the Bible; he will have learned the comfort of both, and hail it as a privilege and blessing. | |

Do not let me be understood to insinuate that a child should not be allowed to pray by himself till he has attained the age of thirteen. Had I children of my own, I would hear them pray in tlioir own simple words and childlike phrases every night before they sank to sleep; a duty quite distinct from family prayer. That has already evinced to the infant mind the necessity of prayer, but it is never too soon to teach a child, that will not do alone; there must be private and individual prayer, or he will never learn, to its full extent, his dependence on the assistance and blessing of his God. A general confession of sin will not come home to his little heart, as the recapitulation of the faults he may have committed, or the errors he may have been led into. A general thanksgiving in the same way, does not awake such real, though perhaps childish gratitude, as the memory of pleasures felt by himself individually in the day just passed. Let a mother recall these things to an affectionate child; if he have been naughty, given way to momentary ill temper, or other faults peculiar to childhood, let her gently and affectionately point out the evil, and impress on his mind the necessity of asking God’s forgiveness, and for the blessing to enable him to become a better boy in future. If any particular pleasure has been his through the day, ask him if he do not think he ought to love and thank his Father in Heaven, who has been so very good to him, and given him kind friends who only seek his happiness. If his lessons are more than usually difficult, teach him to implore the assistance of his Heavenly Father, and assure him if he does so sincerely, and tries all he can himself, he will conquer them. This is prayer; but this can never he taught a child by merely desiring him to learn a set form of words, one-half of which, perhaps, he may not understand. Many think such intimate communion lowers the dignity and destroys the veneration we should feel towards our God — that such little things are unworthy of His regard. But surely this is a false estimate of the universal love that feeds the little birds of the air, and clothes the blossoms of the field; this is judging Him “whose ways are not our ways,” as if He were an earthly sovereign; nor one who has love and care for us all, from the king of a mighty empire, to the virtuous child of the poorest beggar — “As far as the heaven from the earth, so great is His mercy towards those that fear Him.” Can we measure that boundless space, and where would be that deep love if the concerns of a young child were all unworthy of His regard? Oh! do not let us set forth with this idea. It is because we keep so far from Him, we are so loth to address Him in spontaneous prayer, that there is such little comfort for women of Israel. But did we teach this blessed communion with our ever loving, ever seeing Father, Saviour, Friend, unto our children from their earliest infancy, teach them to pray, not in set phrases, hut in the words that the heart teaches, each year would increase the love, the gratitude we bear Him, and the consciousness of His love towards us; and it is this, this consciousness, that is woman’s dearest, strongest, loveliest support. Few are the women that yearn not for love, and what can so fully satisfy that yearning as the consciousness of our Father’s love, far exceeding in its depth, its fulness, its unutterable bliss, the dearest boon to us on earth. But unless we accustom our children to lean on this love, to trust in it, appeal to it, it will be long, very long, ere we realize its comfort in riper years, for we shall fear to approach His footstool for relief and comfort under those innumerable petty trials that form the weary lot of woman. Family prayer will have taught a child veneration to its God. If he have been accustomed to see his mother ever approach His footstool, and open His word with reverence and seriousness, yet with cheerfulness and holy joy, we need have no fear, however simple and childish the words of his prayer may be, but veneration and love will be in his heart: | |

“Father, help me to be a good child, and do all my mother bids me. I have been naughty and quarrelled with my sister (or whatever the fault may be), and given mamma pain; pray forgive me for Thy holy name’s sake, and help me to be good to-morrow.” | |

This is simple, earnest prayer, and our God, who hath promised to hear all who call upon Him, will listen as graciously to those few words — ay, and as mercifully answer them — as He would the more eloquent appeal of weightier sorrows. | |

“Father, I want to try to thank and love Thee for being so good to me and making me so happy, and a good child. Teach me how, for I know Thou lovest little children. I thank and love thee very much.” | |

Such in all probability would be the form in which little children would of themselves pray and praise; and is not this, I ask, more acceptable to Him who demands the heart, not the lips, than a set form they repeat, merely because they are desired to do so? Oh! when we are inclined to think such childlike phrases are unworthy of His notice, let us remember every bird and every flower are guarded by His all-seeing love, and the doubt will fly; for hath He not breathed into the youngest babe an immortal soul, and will not its first aspirations be looked on and heard in love by Him who gave it? | |

A mother alone can do this. Time and trouble and pain it may cost her, but what mother would grudge these for a few brief years, when their fruits may be the everlasting comfort of her offspring through this life — their salvation in eternity? | |

To render a child more attentive to family prayer than he would be, merely from the faculty of imitation, innate within him, a mother could pleasantly and improvingly assist him, by making each sentence the subject of a brief explanation, in words adapted to his understanding. We will take the Shemang for example, the most perfect epitome of man’s moral and religious duty that ever was compiled. We turn to the Word of God, and show that it is there (Deuteronomy, chapter 6, verses 4 to 10) that God inspired Moses to write it for the good of His faithful servants: — “Hear, oh Israel, the Lord our God is one Lord.” Here explain as simply as possible the foundation of our Faith, the unity of our God, that He would be worshipped alone, and bring forward as confirmation of your words the First and Second Commandments: “Blessed be the name of the Lord our God for ever and ever.” Explain why this is not in the Bible; that the compiler of the prayers felt impelled to write it in praise and thanksgiving to his Father in Heaven, for giving him instructions how to live in a manner that would please Him. The next verse divide into three portions; explain to your children, first, that to love their merciful Father with all their heart, they must love Him better than anybody or anything on earth, that as He is kinder to them than their kindest earthly friend, so they ought to love Him more. Secondly, make Soul your subject: that to love Him with all our soul, we must attentively cultivate our talents as His gifts, for as He gave them to us in love. He would justly be displeased if we neglected or abused them, or became proud and conceited, forgetting they are His gifts, and looking on them as our own. In the same way make Might the subject of another Bible lecture, and prove, that to love Him with all our might, we must do all we possibly can to please and serve Him, that even little children can do a great deal by trying to be good and obedient, aflfectionate and attentive to their prayers, and His Holy Word for His sake, that is, because they wish to remember Him and obey His commands. The next verse, closely connected with the Ten Commandments (“These words” referring as well to the chapter previous, as to the verses directly preceding), enables us to explain them at length, making the duties included in each the subject of a separate lesson. The next may also be divided into two parts: the first, “thou shalt teach them diligently,” or, literally translated from the Hebrew, “thou shalt repeat them over and over again to thy children,” as more relating to ourselves than them; but the proof we give that in teaching them we are obeying our Father in Heaven, may do more towards impressing our words on their yielding mind, than the longest sermon. The next paragraph explain, as meaning we must think of Him when we are sitting in the house, or walking by the way, when we lie down, and when we rise up. Pointing out the many things in our walks to associate with Him — the birds, the flowers, the trees, the beautiful blue sky and green fields, all are objects of delight to children, and may be made how much more subservient to their eternal welfare, than merely as emotions of pleasure. The next two verses may impress the necessity of peculiar forms, which we should attend to in obedience to the command of the Lord, even if we cannot see the necessity so much now as when they were given. We are still His chosen people, and His commands are quite as obligatory to us now, as when we were in Jerusalem, and even more necessary, to separate us from the nations now than then. | |

To explain the Shemang, and the morning and evening prayer in this manner, lengthening or shortening our instructions, according to the temper and inclination of our children, is not the work of a day. It may occupy weeks, even months; indeed we should not be satisfied till our children explain them to us as we have to them. But will not the time thus devoted be richly rewarded, if these instructions at length open to their hearts and understandings the exhaustless comfort, the unutterable fulness of fervent and unceasing prayer? How should we despond if years, long weary years run on, ere we can trace any reward for our labour and self-denial? for rigidly and firmly must a mother, who wishes thus to instruct her children, watch herself, that her precepts be confirmed by example, that in her whole conduct she displays their fruits. Of this she may rest assured, that never was fervent and faithful prayer unheard by the God of love, and, therefore, if prayer for His assistance, His blessing, ever accompanying our efforts for our children, we shall be heard, ay, and answered, however long that answer may be deferred, however painful may be our path till it be vouchsafed. | |

A few words on the imperative necessity to make the Word of God, our Bible, our daily companion, and part of the daily instruction of our children, and I have done. The greatest mischief that can be done to the interests of the Jewish religion, is to keep (as too many do) our children from reading an English Bible,[2] This is not the case in America. — American Publisher [A. Hart, late Carey and Hart, 126 Chestnut Street, Philadelphia]. on the plea, that the way in which it is translated will do them more harm than good. Never was there a mistake more egregious than this, or more likely to produce evil consequences. Suppose, as is most likely, intimacy with the Christian ensues; that religious conversation is started; how are we to answer arguments founded on the Bible, if we can produce none from the same holy authority; and how are we to produce them, if the Word of God is never taught us according to our belief, if a Christian be, as is but too often the case, the first person from whose hands we receive an English Bible: if Christian interpretation be the only kind we can receive? Even more necessary to us, in our scattered and forsaken state, is the Word of God, than to the Christian; though by the latter it is made a daily study; by us, with the exception of our Sabbath portions, seldom or never perused — and why? Because we shun the English version, and the Hebrew never can be to us what the English is. There may be mistakes in the translation, but these are comparatively few, and of no consequence, compared with the injury we do ourselves and our children by withholding it entirely; and even this evil is now remedied by a valuable little work just published by a Jew, in which the mistaken renderings are corrected, and the real meanings are attached to them. | |

Imperatively we are called upon to teach the Bible to our children; according to the belief of Judaism, danger threatens if we do not, danger that can only be avoided by making it from early childhood the foundation of their faith, their comfort and their stay; and how can we do this? By showing, even more by example than by precept, that so it is to us; that it is our daily companion, a privilege and a blessing. If we read to them but three or six verses of the narrative part, and as many selected from the Psalms, every day, we shall make a yet stronger impression; for we shall show them we wish them to share the privilege God’s love has granted us. And for this instruction, a child of three or four is not too young. If it sees a mother address her God in prayer, for grace to understand what she is going to read before she opens the sacred book, if it be but one verse she reads and explains as simply as she can to her infant hearers every day when prayers are finished, she may rest assured that book will be regarded by them with as much veneration and love as she can desire. Let her teach them that unless they pray for instruction the Bible must be as a sealed book, and that, even with His teaching, there are many parts they must not expect to understand, but receive with humility and gratitude as the Word of God, which he will explain hereafter. I would make a child acquainted with Scripture history, through the means of Scripture story books, if it felt a wish for them, but I would never put the Bible itself in the hands of a child, to peruse alone, till the age of twelve or thirteen, and not then if it had not learned to venerate and love it. A whole life is inadequate for the thorough understanding of God’s most Holy Word; can we then begin too soon, or think five, ten, even fifteen minutes too long a time to bestow on this important study every day? We think nothing of hours devoted daily to some ornamental accomplishment; but that which is the staiF of life, the guide, the gate unto eternity, we imagine must come of itself to our children. Surely this is wrong; and, if we love the precious gifts a Father’s favour hath bestowed, can we better prove our gratitude to Him, our love to them, than by early opening to them the well of life, and leading them up to Him in “whose presence is the fulness of joy, and pleasures for evermore?” | |

The peculiar language and imagery of the Bible require careful explanation, for not till that is given can we hope to make them really love the book. Amongst Christians, there are many, very many valuable books to assist us in reading the Bible. We, alas! have none; but to those Jewish parents really interested in their tasks, Trimmer’s explanation of the Old Testament for the use of schools, and Burder’s Oriental Literature, would prove invaluable assistants, very few portions of these relating to the doctrines of Christ; and what there are, can easily be left out without injuring the explanation we may wish to give.[3] Only the first sentence of this paragraph appears in the US edition. | |

With regard to the Psalms, I prefer reading them in the Bible, to our prayer books, because the translation appears to me much more simple and clear, and, from their being divided in separate verses, we can better explain them by taking each verse alone; we can also more easily select verses suited to the occasion, or the mood of our children. David’s Psalms are indeed a rich treasury of prayer and praise, and, however our own lips may feel inadequate to express the feelings of our hearts, there we shall find all we need, either in despondency or aspiration, joy or sorrow, doubt or faith, there we shall strike some echoing chord. Oh! can we then open this “fountain of life,” this “rock of strength,” this “well of salvation,” too soon to our children? | |

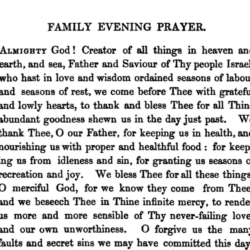

“Be not rash with thy mouth, and let not thy heart be hasty to utter anything before God, for God is in Heaven, and thou upon earth, therefore let thy words be few.” (Ecclesiastes 5:2) Family Morning Prayer Prayer Before Reading the Bible Family Evening Prayer (Additional Portions for Friday Evenings and Saturday Mornings) [Schedule] to Read the Whole of the [Tanakh], with the Exception of the Psalms, in the 52 Weeks of the [Gregorian Calendar] Year Table to Read All the Psalms in One Month |

“Thoughts on Family Prayer,” an essay by Grace Aguilar, was published posthumously by her mother Sarah Aguilar in Essays and Miscellanies (1853), in the section “Sacred Communings,” pp. 131-150. In the UK edition of Sacred Communings (1853) the prayer appears with small variations of spelling and punctuation on pages 143-163.

The UK edition includes a note by Sarah Aguilar that provides something of a date for the essay, twelve years prior to her editing or publication of Sacred Communings, and so we can only say it was written circa 1840. Sarah Aguilar also notes that it was written on behalf of a Mrs. Belinfante. We do not yet know who she was other than to note the Belinfante family were a prominent family of Sefaradim located in the Netherlands and in Germany. If you know anything more about the identity of Mrs. Belinfante, please leave a comment or contact us.

Source(s)

Notes

“Thoughts on Family Prayer, by Grace Aguilar (ca. 1840)” is shared through the Open Siddur Project with a Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication 1.0 Universal license.

Leave a Reply