“The Seven Circuits,” Bernard Picart (1673-1733), c. Royal Library of the Hague. Thanks to Laura Liebman and Mississippi Fred MacDowell for bringing it to our attention.

History

The first Jews in America were Sepharadim. Their ancestors had fled the Spanish and Portuguese Inquisitions and made their way to Holland and from there to the New World. Some of these people had originally settled in South America and fled northward when the Inquisition was instituted in South America. Others made their way directly to the colonies, specifically South Carolina, New York and Rhode Island.[1] ”Early America’s Jewish Settlers” The Gilder-Lehrman Institute of American History

Liturgies and Rituals

Early American Jewry’s liturgies and rituals were conducted in a western Sephardi tradition which had developed in the late 16th and early 17th centuries in Amsterdam. Although most of the members of the first American Jewish communities were of Spanish and Portuguese origins, their worship evolved in the style of the Dutch Sepharadim. These oral transmissions led to adaptations and variations but Sephardi ḥazzanim (cantors) succeeded in passing their repertoire down to succeeding generations. These tunes are still identified with the American Sephardi tradition.

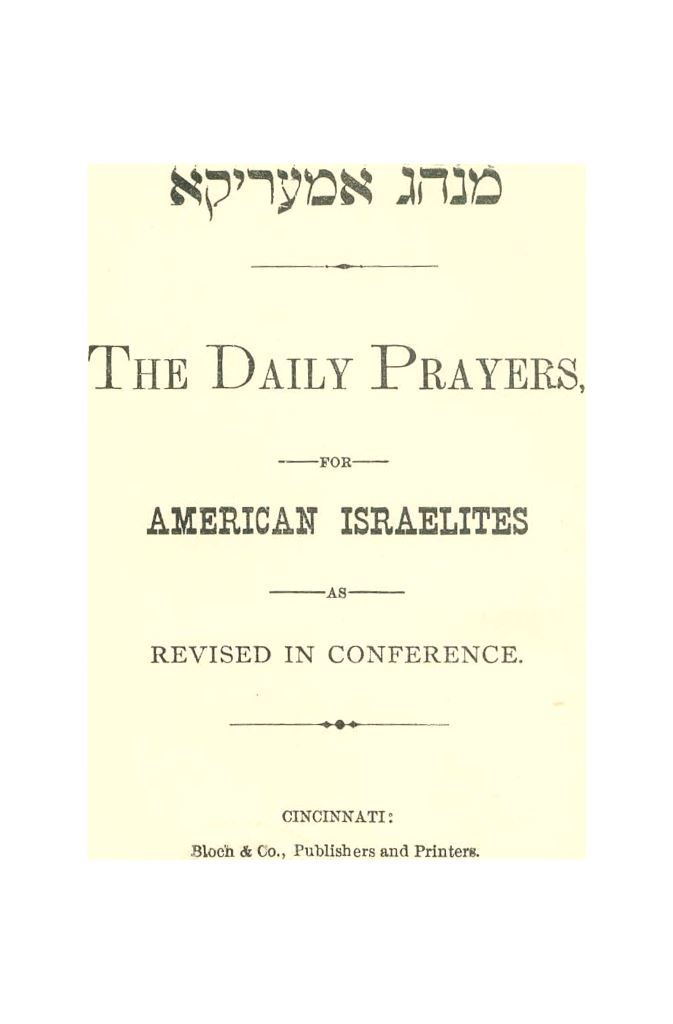

Until the mid-18th century the prayer books used by American Jewish synagogues were those that the Jews had brought from Amsterdam. That changed in the 17th century when Sephardi daily and Sabbath prayer books from London began to be used. The London prayerbooks included both English and Hebrew, a combination that grew increasingly popular as more American Jews adopted English as their day-to-day language.[2] Sharona R. Wachs, American Jewish Liturgies: A Bibliography of American Jewish Liturgy from the Establishment of the Press in the Colonies Through 1925, Hebrew Union College Press, 1997

Colonial Synagogues

Colonial synagogues followed the traditional Sepharadi customs. Congregants preferred the unmodified, traditional service which represented a continuum of their traditions. These traditions included the synagogue’s music which comprised a large part of Jewish worship. Since American Jews of colonial times didn’t establish yeshivot or Jewish schools or even try to bring in rabbis who could help guide the religious life of the community (as did the Jews living in the Caribbean) their religious life centered around their synagogues and they relied on the synagogues to guide them in adhering to authentic Sepharadi liturgical traditions. Most colonial Jews were not observant in the “Orthodox” sense but they saw their synagogue chants and music as the primary vehicle by which their internal Jewish identity was defined.[3] Kerry M. Olitzky, The American Synagogue: A Historical Dictionary and Sourcebook, Greenwood Publishing Group, 1996

The early synagogues included choirs whose primary function was to lead the congregation in singing and in responsive prayers. The choir provided a model that allowed the congregants to follow the service. Throughout the 18th century most of the liturgical tunes were rendered with no harmonization — even as a lay “choir” provided vocal timbre or functioned as an adjunct to the ḥazzan to lead the congregation. In the 19th century synagogues began to harmonize most of the traditional tunes in four parts which were sung in adult male-choir renditions. Lay “choirs” functioned as an adjunct to the ḥazzan to lead the congregation or to provide variety in vocal timbre. Octaves were included if boys were involved in the choirs.

Colonial Melodies

Some colonial melodies of note include:

Baruch HaBa (Tehilim 118:26-29). The last passage of Hallel was often sung in colonial synagogues as a welcome for weddings and other life-cycle events. The Sepharadi melody has a number of variations and is often used when singing Shirat Hayam. It is also used for the Spanish bendigamos birkat hamazon summary. Musical notations for this melody were found in a Dutch manuscript that dates back to the 18th century. Many Sephardim believe that the Baruch Haba tune is an ancient Sephardic melody that dates back to early Jewish settlement on the Iberian peninsula. Baruch Haba was sung in 1782 when the first Philadelphia synagogue, Mikve Israel, was consecrated. During this consecration synagogue dignitaries circled around the ḥazzan‘s reading stand with Sifrei Torah.

The Baruch Haba melody is also used when singing Shira Ḥadasha during the shaḥarit service and has been used extensively in other Sephardic liturgy. The melody was confirmed by a London volume, published in 1857 for the Y’Huda V’Yisrael text which contains similar phrases.

Megillat Eikha, which is chanted on Tishah b’Av, had a special significance for Sephardic Jews of Colonial America. The date of the destruction of the first and second temples coincided with the Spanish expulsion of 1492. The lyric poetry of Eikha, which describes the unbearable sadness and desolation of Jerusalem after the destruction of the First Temple combines with kinot of medieval Hebrew poets to illustrate catastrophes that the Jewish world has ensured.

All communities have their own specific cantillation pattern for the Book of Eikha. Colonial synagogues used the cantillation that was traditional to Portuguese communities. This cantillation was later adopted by the Portuguese Jews of Amsterdam and, subsequently, in the American colonies. A Lisbon manuscript which is believed to date prior to the Spanish Expulsion provides indications of the exact Portuguese melody for the Book of Eikha. This is the tune which was adopted by the Amsterdam community in the 17th century. In America Ḥazzan Mendes Seixas (1745–1816) chanted the traditional tunes of Eikha and these are the tunes that have come down to Sepharadi synagogue Tishah b’Av observance today. Some researchers believe that the tunes were copied from Italian Baroque tunes.

Recordings of many of these melodies and other Colonial American music can be found at the Lowell Milken Archives of Jewish Music.

Religious Belief in Colonial America

The prevailing wisdom which posits that America’s first Jews were not as religiously observant as their co-religionists living in other areas of the world has been challenged with new research into the mystical practices of many of North America’s first Jews. The Spanish and Portuguese expulsions raised messianic hopes and mystical aspirations for Jews who saw, in the turmoil, the hope that the destruction of Spanish and Portuguese Jewry would bring the messiah. Many Jewish leaders of the 16th and 17th centuries preached this belief including some of the leading Sephardic leadership of the era. As was true in Spain, Portugal and Amsterdam there was only a thin line dividing mystical and magical beliefs from modern thinking.

Menasseh ben Israel was a Dutch rabbi who promoted Jewish settlement in the New World. He wrote that he “conceived that our universal dispersion was a necessary circumstance, to be fulfilled, before all that shall be accomplished which the Lord hath promised to the people of the Jews, concerning their restoration and their returning again into their own land.” Rabbi ben Israel wrote these words when the synagogue of Recife was still functioning but following the demise of the small Brazilian Jewish community in the face of the South American Inquisition many new Jewish settlements throughout the Caribbean and in North America adopted the same outlook — the belief that the upheavals of the times were the instrument of messianic redemption.[4] Shalom Me’ir ben Mordekhai Valakh HaCohen, A Chassidic Journey: The Polish Chassidic Dynasties of Lublin, Levov, Feldheim Publishers (2002), p. 155-156

Synagogue Names as Reflections of Messianic Hopes

Names that the Jews of the new American settlements chose for their synagogues reflect their messianic tendencies. Synagogues in Philadelphia, Savannah, Jamaica and Curacao took on the name “Mikve Yisrael” — the name of Rabbi ben Israel’s book which echoed Yirmiyahu’s promise “O Hope of Mikveh Israel, it’s deliverer in the time of trouble” (Yirmiyahu 14:8). The first synagogue of New York, Sherith Israel, was named for Micah’s prophecy “I will bring together the remnant of Shearith Israel” (Micha 2:12). In the Barbados the synagogue, Nidheh Israel, was named for Isaiah’s prophecy “He will hold up a signal to the nations and assemble the banished of Nidheh Israel and gather the dispersed of Judah from the four corners of the earth” (Isaiah 11:12). In Suriname the synagogue was named Bracha VeShalom from a verse in the Zohar — “where is the Garden of Eden? There are found the treasures of good life, bracha v’shalom” (Zohar Midrash haNe’elam). The Touro synagogue’s official name is Yeshuat Yisrael, based on the verse of tehillim “the deliverance of Yeshuat Yisrael might come from Zion when the Lord restores the fortunes of His people Jacob will exult and Israel will rejoice” (Tehillim 14:7).[5] Jonathan D. Sarna, “The Mystical World of Colonial American Jews,” pages 185-190

Other writings from Jews of the era as well as from their Christian neighbors speak to a devout community of committed Jews.

Sources

—. “Jewish Voices in the New World: The Song of Prayer in Colonial and 19th-Century America,” at the Lowell Milken Archives of Jewish Music.

—. “Jews in Colonial America” at Touro Synagogue.

—. “Religion and 18th Century Revivalism” at the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American Jewish History.

ben Mordekhai Valakh HaCohen, Shalom Me’ir. A Chassidic Journey: The Polish Chassidic Dynasties of Lublin, Levov, pages 155 and 156.

Bennett, Ralph G. “History of the Jews of the Caribbean” at sefarad.org

Sarna, Jonathan D. The Mystical World of Colonial American Jews, pages 185-190.

Notes

| 1 | ”Early America’s Jewish Settlers” The Gilder-Lehrman Institute of American History |

|---|---|

| 2 | Sharona R. Wachs, American Jewish Liturgies: A Bibliography of American Jewish Liturgy from the Establishment of the Press in the Colonies Through 1925, Hebrew Union College Press, 1997 |

| 3 | Kerry M. Olitzky, The American Synagogue: A Historical Dictionary and Sourcebook, Greenwood Publishing Group, 1996 |

| 4 | Shalom Me’ir ben Mordekhai Valakh HaCohen, A Chassidic Journey: The Polish Chassidic Dynasties of Lublin, Levov, Feldheim Publishers (2002), p. 155-156 |

| 5 | Jonathan D. Sarna, “The Mystical World of Colonial American Jews,” pages 185-190 |

“Musical Liturgy and Traditions of Colonial American Jews” is shared through the Open Siddur Project with a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International copyleft license.

Leave a Reply