| Source (Hebrew) | Translation (English) |

|---|---|

שדי |

SHADAI |

סנוי סנסנוי סמנגלף אדם וחוה קדמונה חוץ לילית | |

בשם ייי אלהי ישראל יושב הכרובים ששמו חי וקים לעד |

In the name of YHVH Elohei Yisrael seated [upon] the Keruvim, whose Name is living and enduring forever. |

אליהו הנביא היה הולך בדרך ופגע בלילית הרשעה ובכל כת דילה |

Eliyahu haNavi was walking in the road and he met the wicked Lilit and all her horde.[3] Florentina Badalanova Geller notes this tale appears related to the story of Agrat bat Mahlat and her encounter with Rabbi Hanina ben Dosa as recorded in amulet bowls and the Babylonian Talmud (Pesachim 112b). See “Between Demonology and Hagiology: The Slavonic Rendering of the Semitic Magical Historiola of the Child-Stealing Witch” in In the Wake of the Compendia: Infrastructural Contexts and the Licensing of Empiricism in Ancient and Medieval Mesopotamia. ed. J. Cale Johnson (2015), p. 184-185. –ANV |

אמר לה אן את הולכת טמאה ורוח הטומאה וכל כת דילך טמאים הולכים |

He said to her, “Where are you going, Foul one and Spirit of Foulness, walking with all your foul horde?” |

ותען ותאמר לו אדוני אליהו אנכי הולכת לבית היולדה מירקאדה ד״מ[תקריא?] ויאידה בת דונה לתת לה שינת המות ולקחת את ילדה הנולד לה למצוץ דמו ולמצוץ מוח עצמותיו ולחתם את בשרו |

And she answered and said to him: “My lord Eliyahu, I am going to the house of the woman in childbirth Mercada of M.[4] Shaked and Naveh comment (p.118, n.18) that “ד״מ is probably for דמתקריא Vida(?) daughter of Donna.” Viadah bat Donah to give her the sleep of death and to take the child she is bearing, to suck their blood and to suck the marrow of their bones and to devour their flesh.” |

ויאמר לה אליהו הנביא ז״ל [זכרו לברכה] בחרם מאת השם יתברך עצורה תהיה וכאבן דומה תהיה. |

And said Eliyahu haNavi, z”l, to her – “With a ban from the Name (may it be blessed) shall you be restrained and like a tombstone[5] Domah, דומה (“grave, afterworld”). Later girsot have דומם (“inanimate”). An u-kh’even domah should translate as ‘like a stone of the netherworld,’ i.e., a tombstone. Others translate this as “like a dumb stone.” –ANV shall you be!” |

ותען ותאמר לו למען ייי התירני מן החרם ואנכי אברח ואשבע לך בשם ייי אלהי ישראל לעזוב את הדרכים אלו מהיולתת הזאות ומולדה הנולד לה ומכל שכן להזיק וכל זמן שמזכירים או אני רואה את שמותי כתובים לא יהיה לי וכל כת דילי כח להרע ולהזיק ואלו הן שמותי: לילית אביטו אכיזו אמורפו הקש אודם איכפידו איילו מטרוטה אבנוקטה שטריגה קלי בטזה תלתוי ריטשה׃ |

And she answered and said to him: “For the sake of YHVH postpone the ban and I will flee and will swear to you in the name of YHVH Elohei Yisrael that I will let go this business in the case of this woman in childbirth and the child to be born to her and every pregnant woman so as to do no harm. And every time they are repeated or I see my names written, it will not be in the power of me or of all my horde to do evil or harm. And these are my names:[6] The order of corresponding names diverges slightly in parallel texts. Some differences of transliteration are due to the vocalization as interpreted by the scribe/copyist, others are due to common confusion in letters (e.g. daled and resh in the name Odam vs. Orem. –ANV Lilit, Abitu,[7] ”or Abatur, the Mandaic genius, but the possible reading of the copy, Abito, may be preferable, in view of the Greek parallels” (Gottheil in Montgomery 1913). Abito is also found in a similar albeit abbreviated text cited by Moses Gaster, Mystery of the Lord (the original Hebrew title, unclear, but possibly סודי ה׳, a book that both Montgomery and I have yet to locate). Florentina Badalanova Geller, in “Between Demonology and Hagiology” (2015) also cites a text from an 18th-century Jewish amulet of German provenance, published by Maria Kaspina from the collection of The Museum of the History of the Jews in Russia ((Амулет для девочки, Германия, 18 век, Музей истории евреев в России, 3473-т6). Geller translates Kaspina’s translation in Russian as published in “Илья Пророк и демоны в еврейских магических текстах (сборники заговоров и амулеты 18–20 вв.).” In: Д. И. Антонов, О. Б. Христофорова (eds). Российский государственный гуманитарный университет, Центр типологии и семиотики фольклора, Отделение социокультурных исследований, Третья научная конференция: “Демонология как семиотическая система.” Москва, РГГУ. 15–17 мая 2014 г. ТЕЗИСЫ ДОКЛАДОВ. Москва 2014, 49–51. I believe the original amulets from which her transcriptions were derived are here and here. There, the name is אַבִּיטִוּ (Abitu). A third comparative text, in Hebrew and Yiddish from the collection of the Jewish Museum Prague (inventory number JMP 178.801) was also recently published by Lenka Uličná in “Amulets Found in Bohemian Genizot: A First Approach,” p.71-75 in Genisa-Blätter III. There the name is אַבִיטִי (Abiti). Akizu,[8] In the text cited by Gaster, Abiko. In the amulets cited by Kaspina and Uličná — אַבִּיזוּ. Amorpho[9] i.e., “amorphous, shapeless” Gk. ἂμορϕος. Gottheil notes, “our Jewish text alone has preserved the correct form.” In the text cited by Gaster, Amizo. In the amulets cited by Kaspina and Uličná — אַמְזַרְפּוֹ. Haqash[10] Gk. κακός. In the text cited by Gaster, Koko. In the amulets cited by Kaspina and Uličná — הַקַשׁ. Odem,[11] In the amulets cited by Kaspina and Uličná — אוֹדֶם. Ikpido,[12] In the text cited by Gaster, Podo. In the amulets cited by Kaspina and Uličná — אִיקְפוֹדוּ. Eilo,[13] In the amulets cited by Kaspina and Uličná — אִיְילוּ. Matrotah,[14] In the text cited by Gaster, Patrota. In the amulets cited by Kaspina and Uličná — טַטְרוֹטָה. Abnuqtah,[15] In the amulets cited by Kaspina and Uličná — אֲבַנוּקְטָה. Shatrigah,[16] In the text cited by Gaster, Satrina. In the amulets cited by Kaspina and Uličná — שַׁטְרוּנָה. Ḳali,[17] Is this name the same as Kali, the Hindu goddess? In her Indian context, she is the destroyer of evil forces, rather than a personification of malevolence, as Lilith is here. Perhaps this occurrence is only a coincidence, but it still seems remarkable to me. In the amulets cited by Kaspina and Uličná — קַלִיכַּטַזָה (Ḳalikataza), combining Ḳali and the following name in this amulet, Batzeh, with the letter “בּ” (bet) in Batzeh made into the letter “כּ” (kaf), the result of an obvious scribal or printers error. Batzeh,[18] This name is included in Montgomery’s translation but does not appear in his publication of Gottheil’s transcription. I’ve transcribed it from the source. In the text cited by Gaster, Batna. The name appears combined with Ḳali (as Kalikatazah) in the later attestations of the amulet text (find note on the amulets of Kaspina and Uličná above). Taltui,[19] In the text cited by Gaster, Talto. In the amulets cited by Kaspina and Uličná — תִּילָתוּי. Ritshah.[20] In the text cited by Gaster, Partasah. In the amulets cited by Kaspina and Uličná — פִירַטְשָׁה. ” |

והשיב לה אליהו הנביא ז״ל ואמר לה הריני משביעך ולכל כת דילך בשם ייי אלהי ישראל גי״ם תיריג אברהם יצחק ויעקב ובשם שכינתו הקדושה ובכח עשרה שרפים אופנים וחיות הקדש ועשרה ספרי תורה ובכח אלהי הצבאות ב״ה שלא תלכי לא את ולא מכת דילך להזיק את היולדת הזאת או את ילדה הנולד לה לא לשתות את דמו ולא למצוץ מיח עצמותיו ולא לחתם את בשרו ולא ליגע בהם לא ברנ״ב אבריהן ולא בשס״ה גידיהן וערקיהן כמו שאינה יכולה לספור את כוכבי השמים ולא להוביש את מי הים בשם קר״ע שט״ן׃ חסדיאל שמריאל |

And Eliyahu haNavi (z”l) answered and said to her: “Lo, I adjure thee and all your horde, in the name of YHVH Elohei Yisrael, by the gematria of 613,[21] the figure of 613 is the gematria for ‘YHVH Elohei Yisrael,’ and the traditionally enumerated number of obligatory and prohibitory commandments in the Torah. –ANV after Montgomery Avraham, Yitsḥaq and Yaaqov, and in the name of his holy Shekhinah, and with the might of ten holy Serafim, Ofanim and Ḥayot haḳodesh[22] lit., the wheels and the sacred creatures or the wild creatures. Likely a reference to the sphere of the cosmos and its zodiacal constellations, as living cosmic or “angelic” entities. –ANV and ten Sifrei Torah, and by the might of Elohei Tsevaot (b”h) – that you come not, you nor your horde to injure this woman or the child she is bearing, nor to drink its blood nor to suck the marrow of its bones nor to devour its flesh, nor to touch them neither in their 256 limbs[23] The “256 limbs” are 248 in Jewish lore. “This tradition harks back to a Talmudic dictum that the body has 248 bones and 365 sinews, which add up to 613, equal to the number of Mosaic commandments in the Pentateuch; this relates to a Talmudic account of the first-century CE Palestinian sage Rabbi Ishmael, whose students dissected the body of a prostitute and were surprised to discover that she had 252 bones (rather than 248), the problem being solved by the explanation that a woman has four additional bones (doors and hinges) in her vagina (Bekhorot 45a). The theme is fairly common in Aramaic magic bowls, which also distinguish between 252 bones for females and 248 bones in males; see Shaked, Ford & Bhayro 2013, 55. See also two magic bowls published by Dan Levene in which a male client is to be protected by the spell in all his 248 limbs, and alternatively the demon is forbidden from harming a female client in all her 252 limbs (Levene 2003, 46, 116).” –note 25 in Florentina Badalanova Geller’s “Between Demonology and Hagiology: The Slavonic Rendering of the Semitic Magical Historiola of the Child-Stealing Witch” in In the Wake of the Compendia: Infrastructural Contexts and the Licensing of Empiricism in Ancient and Medieval Mesopotamia. ed. J. Cale Johnson (2015). –ANV nor in their 365 ligaments and veins, even as you are unable to count the number of the stars of heaven nor dry up the water of the sea. In the name of QRA STN.[24] An acrostic line found in the 42-letter divine name. Ḥasdiel Shamriel. |

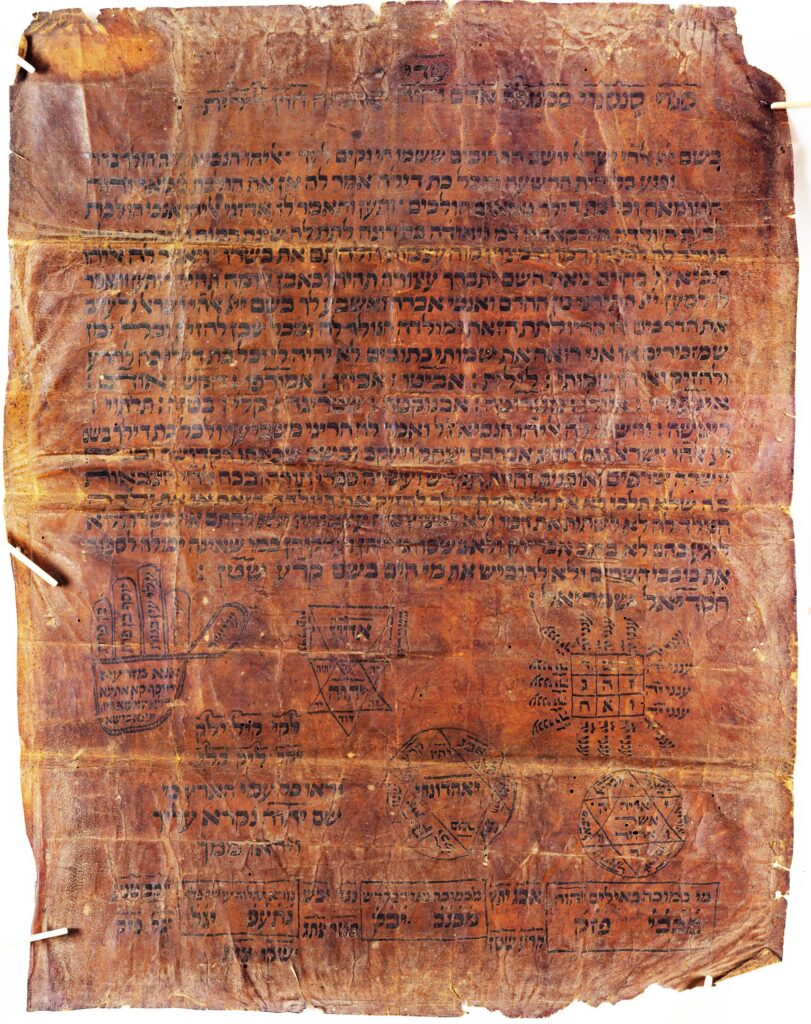

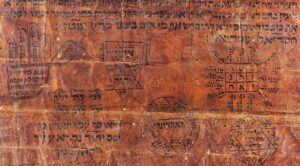

After his translation, Montgomery includes the following important details relayed by Gottheil:

Accompanying the text are given some inscribed designs and phrases. A rough figure of a hand (prophylactic against the evil eye) contains the Aramaic legend:

אנא מזרעי דיוסף קא (=הא?) אתינא ולא שלטא ביה שנא בישא

“I am the seed-producer (?) of Yosef; when I come, an evil year cannot prevail over him,”—a play of thought between Yosef as controller of the fertility of Egypt and the fertility of the family, and as a good omen for the expectant mother.

A “David’s Shield” contains in the center יאהדונהי, a [combined form of the Tetragrammaton with] Adonai. On the left hand שטן…in another division אבג and nearby יתץ, i.e. אבג״יתץ, [from the 42-letter divine name –ANV] to be found in Schwab, Vocab. Another species of the shield more roughly designed contains יהוה in the center, flanked with יה, etc. and אדני, with מטטרון and סנדלפון on either side. The changes are rung on the possible mutations of ילק, and the scripture Deuteronomy 28:10 is cited. Similar charms against the Lilith are to be found at the end of Sefer Raziel and in Buxtorf’s Lexicon, s.v.

The presence of portions of the 42-letter divine name found in Sefer Raziel ha-Malakh (ca. 13th c.) and described by Hai Gaon (939-1038), indicates to me that this variation of the text dates no earlier than the late Geonic period. Shorter versions of this text reproduced in later periods commonly end with the litany of Lilit’s names and omit the adjuration of Eliyahu.

Montgomery offers an additional insight for this Lilit text in the context of the stories appearing in the bowls he reviewed earlier: “The very ancient use of epical narrative as an efficient magical charm was described above p. 62; thus the mere narrative of a demon’s power as in the case of Dibbarra, is potent, or, à fortiori, the relation of a triumph over the evil spirit from some sacred legend. In the present case we have the added virtue of the revelation of the demon’s names, and she swears that whenever they confront her, she will retire; the knowledge of her names binds her (cf. p. 56).”

The source from which this transcription was derived appeared to me to have been lost,[25] Shaked and Naveh comment “The provenance of that amulet is uncertain, but there can be no doubt that it is not part of the Nippur excavation material, despite Montgomery’s wavering on this point. The language and style are clearly late medieval or modern (Scholem 1948, “פרקים חדשים מענייני אשמדאי ולילית” תרביץ יט׳” p. 166, n. 25). Montgomery’s text seems to come from an area where Spanish was used. The name of the young mother to whose house Lilith goes may be read as Mercada who is known as (ד״מ is probably for דמתקריא) Vida (?), daughter of Donna.” (p.118, n.18) but by chance, I found an image of the manuscript posted to Twitter from the Columbia Hebrew Manuscripts collection with a link to the digital source posted to the Internet Archive. In the collection, the manuscript is known as MS General 194. (When Gottheil died in 1936, his papers ultimately landed at the American Jewish Archives in Cincinnati, Ohio, but this manuscript and sundry other documents found their home at Columbia. Thanks to Michelle Chesner at Columbia for this information.)

I’ve provided a derivation of the source image below. I’ve altered the contrast in the image to improve its legibility. The manuscript conforms exactly to the girsah of the text as published by Montgomery along with his description of its accompanying segulot.

From the manuscript, I have corrected obvious errors in the transcription published by Montgomery (and corrected the latter’s translation). I have included the notes published by Montgomery where significant. See below, “Sources,” for Montgomery’s original article and complete notes including his important reference to a similar work quoted in translation by Moses Gaster in “Two Thousand Years of the Child-Stealing Witch” (1900) in Folk-lore 11(2), 129–162. –Aharon Varady

Source(s)

Qame’a for Mirḳada d’M. Ṿiadah bat Donah] (in MS General 194 at Columbia Hebrew Manuscripts Collection)

Notes

| 1 | Protecting angels common in childbirth charms whose significance to wards against Lilith is explained in the Alphabet of ben Sira. |

|---|---|

| 2 | i.e., another name for Lilith. –ANV |

| 3 | Florentina Badalanova Geller notes this tale appears related to the story of Agrat bat Mahlat and her encounter with Rabbi Hanina ben Dosa as recorded in amulet bowls and the Babylonian Talmud (Pesachim 112b). See “Between Demonology and Hagiology: The Slavonic Rendering of the Semitic Magical Historiola of the Child-Stealing Witch” in In the Wake of the Compendia: Infrastructural Contexts and the Licensing of Empiricism in Ancient and Medieval Mesopotamia. ed. J. Cale Johnson (2015), p. 184-185. –ANV |

| 4 | Shaked and Naveh comment (p.118, n.18) that “ד״מ is probably for דמתקריא Vida(?) daughter of Donna.” |

| 5 | Domah, דומה (“grave, afterworld”). Later girsot have דומם (“inanimate”). An u-kh’even domah should translate as ‘like a stone of the netherworld,’ i.e., a tombstone. Others translate this as “like a dumb stone.” –ANV |

| 6 | The order of corresponding names diverges slightly in parallel texts. Some differences of transliteration are due to the vocalization as interpreted by the scribe/copyist, others are due to common confusion in letters (e.g. daled and resh in the name Odam vs. Orem. –ANV |

| 7 | ”or Abatur, the Mandaic genius, but the possible reading of the copy, Abito, may be preferable, in view of the Greek parallels” (Gottheil in Montgomery 1913). Abito is also found in a similar albeit abbreviated text cited by Moses Gaster, Mystery of the Lord (the original Hebrew title, unclear, but possibly סודי ה׳, a book that both Montgomery and I have yet to locate). Florentina Badalanova Geller, in “Between Demonology and Hagiology” (2015) also cites a text from an 18th-century Jewish amulet of German provenance, published by Maria Kaspina from the collection of The Museum of the History of the Jews in Russia ((Амулет для девочки, Германия, 18 век, Музей истории евреев в России, 3473-т6). Geller translates Kaspina’s translation in Russian as published in “Илья Пророк и демоны в еврейских магических текстах (сборники заговоров и амулеты 18–20 вв.).” In: Д. И. Антонов, О. Б. Христофорова (eds). Российский государственный гуманитарный университет, Центр типологии и семиотики фольклора, Отделение социокультурных исследований, Третья научная конференция: “Демонология как семиотическая система.” Москва, РГГУ. 15–17 мая 2014 г. ТЕЗИСЫ ДОКЛАДОВ. Москва 2014, 49–51. I believe the original amulets from which her transcriptions were derived are here and here. There, the name is אַבִּיטִוּ (Abitu). A third comparative text, in Hebrew and Yiddish from the collection of the Jewish Museum Prague (inventory number JMP 178.801) was also recently published by Lenka Uličná in “Amulets Found in Bohemian Genizot: A First Approach,” p.71-75 in Genisa-Blätter III. There the name is אַבִיטִי (Abiti). |

| 8 | In the text cited by Gaster, Abiko. In the amulets cited by Kaspina and Uličná — אַבִּיזוּ. |

| 9 | i.e., “amorphous, shapeless” Gk. ἂμορϕος. Gottheil notes, “our Jewish text alone has preserved the correct form.” In the text cited by Gaster, Amizo. In the amulets cited by Kaspina and Uličná — אַמְזַרְפּוֹ. |

| 10 | Gk. κακός. In the text cited by Gaster, Koko. In the amulets cited by Kaspina and Uličná — הַקַשׁ. |

| 11 | In the amulets cited by Kaspina and Uličná — אוֹדֶם. |

| 12 | In the text cited by Gaster, Podo. In the amulets cited by Kaspina and Uličná — אִיקְפוֹדוּ. |

| 13 | In the amulets cited by Kaspina and Uličná — אִיְילוּ. |

| 14 | In the text cited by Gaster, Patrota. In the amulets cited by Kaspina and Uličná — טַטְרוֹטָה. |

| 15 | In the amulets cited by Kaspina and Uličná — אֲבַנוּקְטָה. |

| 16 | In the text cited by Gaster, Satrina. In the amulets cited by Kaspina and Uličná — שַׁטְרוּנָה. |

| 17 | Is this name the same as Kali, the Hindu goddess? In her Indian context, she is the destroyer of evil forces, rather than a personification of malevolence, as Lilith is here. Perhaps this occurrence is only a coincidence, but it still seems remarkable to me. In the amulets cited by Kaspina and Uličná — קַלִיכַּטַזָה (Ḳalikataza), combining Ḳali and the following name in this amulet, Batzeh, with the letter “בּ” (bet) in Batzeh made into the letter “כּ” (kaf), the result of an obvious scribal or printers error. |

| 18 | This name is included in Montgomery’s translation but does not appear in his publication of Gottheil’s transcription. I’ve transcribed it from the source. In the text cited by Gaster, Batna. The name appears combined with Ḳali (as Kalikatazah) in the later attestations of the amulet text (find note on the amulets of Kaspina and Uličná above). |

| 19 | In the text cited by Gaster, Talto. In the amulets cited by Kaspina and Uličná — תִּילָתוּי. |

| 20 | In the text cited by Gaster, Partasah. In the amulets cited by Kaspina and Uličná — פִירַטְשָׁה. |

| 21 | the figure of 613 is the gematria for ‘YHVH Elohei Yisrael,’ and the traditionally enumerated number of obligatory and prohibitory commandments in the Torah. –ANV after Montgomery |

| 22 | lit., the wheels and the sacred creatures or the wild creatures. Likely a reference to the sphere of the cosmos and its zodiacal constellations, as living cosmic or “angelic” entities. –ANV |

| 23 | The “256 limbs” are 248 in Jewish lore. “This tradition harks back to a Talmudic dictum that the body has 248 bones and 365 sinews, which add up to 613, equal to the number of Mosaic commandments in the Pentateuch; this relates to a Talmudic account of the first-century CE Palestinian sage Rabbi Ishmael, whose students dissected the body of a prostitute and were surprised to discover that she had 252 bones (rather than 248), the problem being solved by the explanation that a woman has four additional bones (doors and hinges) in her vagina (Bekhorot 45a). The theme is fairly common in Aramaic magic bowls, which also distinguish between 252 bones for females and 248 bones in males; see Shaked, Ford & Bhayro 2013, 55. See also two magic bowls published by Dan Levene in which a male client is to be protected by the spell in all his 248 limbs, and alternatively the demon is forbidden from harming a female client in all her 252 limbs (Levene 2003, 46, 116).” –note 25 in Florentina Badalanova Geller’s “Between Demonology and Hagiology: The Slavonic Rendering of the Semitic Magical Historiola of the Child-Stealing Witch” in In the Wake of the Compendia: Infrastructural Contexts and the Licensing of Empiricism in Ancient and Medieval Mesopotamia. ed. J. Cale Johnson (2015). –ANV |

| 24 | An acrostic line found in the 42-letter divine name. |

| 25 | Shaked and Naveh comment “The provenance of that amulet is uncertain, but there can be no doubt that it is not part of the Nippur excavation material, despite Montgomery’s wavering on this point. The language and style are clearly late medieval or modern (Scholem 1948, “פרקים חדשים מענייני אשמדאי ולילית” תרביץ יט׳” p. 166, n. 25). Montgomery’s text seems to come from an area where Spanish was used. The name of the young mother to whose house Lilith goes may be read as Mercada who is known as (ד״מ is probably for דמתקריא) Vida (?), daughter of Donna.” (p.118, n.18) |

“קמע לשמירה מפני לילית | Apotropaic ward for the protection of pregnant women and infants against Lilith & her minions (CUL MS General 194, Montgomery 1913 Amulet No. 42)” is shared through the Open Siddur Project with a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International copyleft license.

Leave a Reply