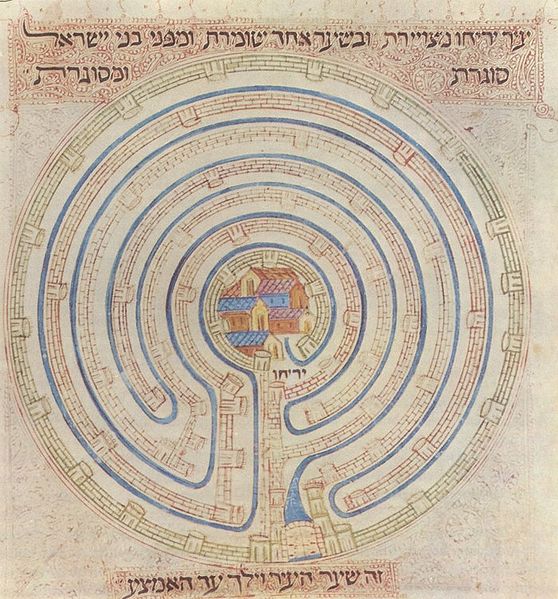

Yeriḥo as a seven walled Cretan labyrinth. (Farḥi Bible by Elisha ben Avraham Crescas, 14th cen.) The seven walls of Yericho are alluded to in the seven verses of Psalms 67.

| Source (Hebrew) | Translation (English) |

|---|---|

א לַמְנַצֵּ֥ח בִּנְגִינֹ֗ת מִזְמ֥וֹר שִֽׁיר׃ |

1 For the Leader; with string-music. A Psalm, a Song. |

ב אֱלֹהִ֗ים יְחָנֵּ֥נוּ וִֽיבָרְכֵ֑נוּ יָ֤אֵ֥ר פָּנָ֖יו אִתָּ֣נוּ סֶֽלָה׃ |

2 Elohim be gracious unto us, and bless us; May Elohim cause their face to shine toward us;[2] cf. the Priestly Blessing: Numbers 6:23–27 Selah |

ג לָדַ֣עַת בָּאָ֣רֶץ דַּרְכֶּ֑ךָ בְּכָל־גּ֝וֹיִ֗ם יְשׁוּעָתֶֽךָ׃ |

3 That your way may be known upon earth, Your salvation among all peoples. |

ד יוֹד֖וּךָ עַמִּ֥ים׀ אֱלֹהִ֑ים י֝וֹד֗וּךָ עַמִּ֥ים כֻּלָּֽם׃ |

4 Let the peoples give thanks unto you, Elohim; Let the peoples give thanks unto you, all of them. |

ה יִֽשְׂמְח֥וּ וִֽירַנְּנ֗וּ לְאֻ֫מִּ֥ים כִּֽי־תִשְׁפֹּ֣ט עַמִּ֣ים מִישׁ֑וֹר וּלְאֻמִּ֓ים׀ בָּאָ֖רֶץ תַּנְחֵ֣ם סֶֽלָה׃ |

5 O let the nations be glad and sing for joy; For you will judge the peoples with equity, And guide the people upon earth. Selah |

ו יוֹד֖וּךָ עַמִּ֥ים׀ אֱלֹהִ֑ים י֝וֹד֗וּךָ עַמִּ֥ים כֻּלָּֽם׃ |

6 Let the peoples give thanks unto you, Elohim; Let the peoples give thanks unto you, all of them. |

ז אֶ֭רֶץ נָתְנָ֣ה יְבוּלָ֑הּ יְ֝בָרְכֵ֗נוּ אֱלֹהִ֥ים אֱלֹהֵֽינוּ׃ |

7 The earth has granted her harvest; May Elohim, our Elohim, bless us. |

ח יְבָרְכֵ֥נוּ אֱלֹהִ֑ים וְיִֽירְא֥וּ אֹ֝ת֗וֹ כָּל־אַפְסֵי־אָֽרֶץ׃ |

8 May Elohim bless us; And let all the ends of the earth be in awe of them. |

Ana b’Khoaḥ is one of the masterpieces of mystical prayer. You’ll notice something unusual about Ana b’Khoaḥ: the word “God” does not appear, nor do any traditional names for God like Adonai-YHVH or eloheinu. Like the Kaddish, Ana b’Khoaḥ addresses the divine at a level that is beyond the names for God that we normally use. This special language makes it a very powerful prayer, whether it’s said in (well-translated) English or Hebrew.

How to use Ana b’Khoaḥ

Ana b’Khoaḥ is traditionally recited right before L’kha Dodi on Friday night, which makes it easy to fit into the Kabbalat Shabbat service even if it doesn’t appear in your prayerbook. (It’s also recited after counting the omer and even as part of lighting the Menorah.) One way to introduce the prayer to a community that hasn’t seen it before is for the shaliaḥ tsibur (prayer leader) to chant each line in Hebrew, and then have the community respond by chanting or reading the corresponding line in English.

While Ana b’Khoaḥ is sung aloud in many communities, it’s also traditional to recite Ana b’Khoaḥ in a whisper, reflecting the mystical idea that the initial letters of Ana b’Khoaḥ spell out the secret 42-letter name (or names) of G!D. Because of this belief, the line “Barukh Shem K’vod…” (Blessed be the name…) is added after the last verse of the prayer.

| Acrostic | Source (Hebrew) | Translation (English) |

|---|---|---|

אב״ג ית״ץ |

אָנָּא בְּכֹחַ גְּדֻלַּת יְמִינְךָ תַּתִּיר צְרוּרָה |

Please, with the power of Your great right hand free the bound. |

קר״ע שט״ן |

קַבֵּל רִנַּת עַמְּךָ שַׂגְּבֵנוּ טַהֲרֵנוּ נוֹרָא |

Accept the song of Your people, empower us, make us pure, Awesome One! |

נג״ד יכ״ש |

נָא גִבּוֹר, דּוֹרְשֵׁי יִחוּדְךָ, כְּבָבַת שָׁמְרֵם |

Please, Mighty One, the seekers of Your unity, watch them like the pupil of an eye. |

בט״ר צת״ג |

בָּרְכֵם טַהֲרֵם, רַחֲמֵי צִדְקָתְךָ, תָּמִיד גָּמְלֵם |

Bless them, make them pure, have mercy on them; Your justness bestow upon them always. |

חק״ב טנ״ע |

חָסִין קָדוֹשׁ, בְּרֹב טוּבְךָ, נַהֵל עֲדָתֶךָ |

Tremendous Holy One, in Your abundant goodness guide Your community. |

יג״ל פז״ק |

יָחִיד גֵּאֶה, לְעַמְּךָ פְּנֵה, זוֹכְרֵי קְדֻשָּׁתֶךָ |

Unique One, Exalted One, face Your people who remember Your holiness. |

שק״ו צי״ת |

שַׁוְעָתֵנוּ קַבֵּל, וּשְׁמַע צַעֲקָתֵנוּ, יוֹדֵעַ תַּעֲלוּמוֹת |

Accept our prayer, hear our cry, Knower of secrets. |

בָּרוּךְ שֵׁם כְּבוֹד מַלְכוּתוֹ לְעוֹלָם וָעֶד: |

Blessed is the Name of the resplendent Kingdom in the Cosmos forever. |

Rav Avidmi in Talmud Bavli Shabbat 88a provides a midrash to Exodus 19:17 (referred to by Rashi) that to receive the Torah, bnei Yisrael went beneath Har Sinai, submitting to the labyrinth of a new redemptive halakhah. As I travel towards receiving gnosis in the theophany of revelation, I recommit myself to the covenants between G!D and bnei Noaḥ (justice for all humanity without acting as a predator) and between G!D and bnei Yisrael (opposing and redeeming predatory nature in all of my actions). I traverse the walls of my internal seven walled labyrinth, channeling the voice of Shalma ben Naḥson (ben Amindav):

Scaling walls with Raḥab’s

scarlet twine, we escape

and liberate worlds

The words of Psalms 67 and Ana B’khoaḥ are the footholds directing my intention. Saving me are my friends — all the earth’s peoples, who like Raḥab, seek liberation.

The translation of Psalm 67 is adapted from the JPS 1917 translation. The translation of Ana b’Khoaḥ is based on a translation by Rabbi David Seidenberg. I am not aware of any other teaching relating the sefirat haomer to the labyrinth. Do you know of any other teachings relating the labyrinth to the journey of the Israelites towards Har Sinai, or Moshe into Har Sinai? Please share your thoughts and knowledge in the comments.

“📄 Scaling the Walls of the Labyrinth: Psalms 67 and Ana b’Khoaḥ” is shared through the Open Siddur Project with a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International copyleft license.

I wasn’t really finished thinking and writing about the idea of Sefirat haOmer as labyrinth when I posted this dvar tefillah on Psalms 67 and Ana B’Koach last night. I wasn’t aware of any labyrinths being explicitly mentioned in the TaNaKh and so was fascinated to find one explicitly illustrated in a medieval bible in the context of Jericho. Seeing the image of a labyrinthine seven walled Jericho, thinking about the typical number of walls in a Cretan labyrinth, and trying to unpack what it could mean for the 7×7 counting of the Sefirat haOmer, blew my mind. Labyrinths are found in almost every spiritual tradition. They’ve become more commonly used for contemplative praxis in Catholic Christian tradition, although they predate Christianity and are found across the Mediterranean and as far east as India. What might a particularly Jewish take on the Labyrinth be? Outside of the course of the agricultural calendar on which we are dependant, what are the other labyrinths that impose themselves on our minds, their imaginative limits, and our actions? In our lives there are superimposing labyrinths: halakhah, socio-cultural conventions and expectations, etc. I think a particularly Rabbinic Jewish take on the labyrinth would be an attempt to attain gnosis though a recognition and subversion of the labyrinth itself, by creative theurgical and hermenutical means. Your comments are welcome.

Yasher koach! Thank you for your reflections and for the Open SIddur Project. You might find the article “The Jericho Labyrinth: The Rise and Fall of a Jewish Visual Trope,” by Daniel Stein Kokin, of interest. It is available online at http://www.academia.edu/1965828/The_Jericho_Labyrinth_The_Rise_and_Fall_of_a_Jewish_Visual_Trope.

You’re welcome and thank you. Fascinating.

I keep coming back to this article. It’s important for me. Thanks again Avraham.

Shalom ! it is 3:44am. Just found this link. Very fascinating and I am in awe! Thank you so much.