| Source (German) | Translation (English) |

|---|---|

Prinzessin Sabbat |

Princess Shabbat |

In Arabiens Mährchenbuche Sehen wir verwünschte Prinzen, Die zu Zeiten ihre schöne Urgestalt zurückgewinnen: |

In Arabia’s book of fable We behold enchanted princes Who at times their form recover, Fair as first they were created. |

Das behaarte Ungeheuer Ist ein Königssohn geworden; Schmuckreich glänzend angekleidet, Auch verliebt die Flöte blasend. |

The uncouth and shaggy monster Has again a king for father; Pipes his amorous ditties sweetly On the flute in jewelled raiment. |

Doch die Zauberfrist zerrinnt, Und wir schauen plötzlich wieder Seine königliche Hoheit In ein Ungethüm verzottelt. |

Yet the respite from enchantment Is but brief, and, without warning, Lo! we see his Royal Highness Shuffled back into a monster. |

Einen Prinzen solchen Schicksals Singt mein Lied. Er ist geheißen Israel. Ihn hat verwandelt Hexenspruch in einen Hund. |

Of a prince by fate thus treated Is my song. His name is Israel, And a witch’s spell has changed him To the likeness of a dog. |

Hund mit hündischen Gedanken, Kötert er die ganze Woche Durch des Lebens Koth und Kehricht, Gassenbuben zum Gespötte. |

As a dog, with dog’s ideas. All the week, a cur, he noses Through life’s filthy mire and sweepings, Butt of mocking city Arabs; |

Aber jeden Freitag Abend, In der Dämmrungstunde, plötzlich Weicht der Zauber, und der Hund Wird aufs Neu’ ein menschlich Wesen. |

But on every Friday evening, On a sudden, in the twilight, The enchantment weakens, ceases, And the dog once more is human. |

Mensch mit menschlichen Gefühlen, Mit erhobnem Haupt und Herzen, Festlich, reinlich schier gekleidet, Tritt er in des Vaters Halle. |

And his father’s halls he enters As a man, with man’s emotions, Head and heart alike uplifted, Clad in pure and festal raiment. |

„Sei gegrüßt, geliebte Halle Meines königlichen Vaters! Zelte Jakob’s, Eure heil’gen Eingangspfosten küßt mein Mund!“ |

“Be ye greeted, halls beloved, Of my high and royal father! Lo! I kiss your holy mezuzot, Tents of Jacob, with my mouth!” |

Durch das Haus geheimnißvoll Zieht ein Wispern und ein Weben, Und der unsichtbare Hausherr Athmet schaurig in der Stille. |

Through the house there passes strangely A mysterious stir and whisper, And the hidden master’s breathing Shudders weirdly through the silence. |

Stille! Nur der Seneschall (Vulgo Synagogendiener) Springt geschäftig auf und nieder, Um die Lampen anzuzünden. |

Silence! save for one, the shammes (Vulgo: synagogue attendant) Springing up and down, and busy With the lamps that he is lighting. |

Trostverheißend goldne Lichter, Wie sie glänzen, wie sie glimmern! Stolz aufflackern auch die Kerzen Auf der Brüstung des Almemors. |

Golden lights of consolation, How they sparkle, how they glimmer! Proudly flame the candles also On the rails of the Almemor. |

Vor dem Schreine, der die Thora Aufbewahret, und verhängt ist Mit der kostbar seidnen Decke, Die von Edelsteinen funkelt – |

By the shrine wherein the Torah Is preserved, and which is curtained By a costly silken hanging, Whereon precious stones are gleaming. |

Dort an seinem Betpultständer Steht schon der Gemeindesänger; Schmuckes Männchen, das sein schwarzes Mäntelchen kokett geachselt. |

There, beside the desk already Stands the synagogue Ḥazzan. Small and spruce, his mantle black With an air coquettish shouldering; |

Um die weiße Hand zu zeigen, Haspelt er am Halse, seltsam An die Schläf’ den Zeigefinger, An die Kehl’ den Daumen drückend. |

And, to show how white his hand is. At his neck he works — forefinger Oddly pressed against his temple. And the thumb against his throat. |

Trällert vor sich hin ganz leise, Bis er endlich lautaufjubelnd Seine Stimm’ erhebt und singt: Lecho Daudi Likras Kalle! |

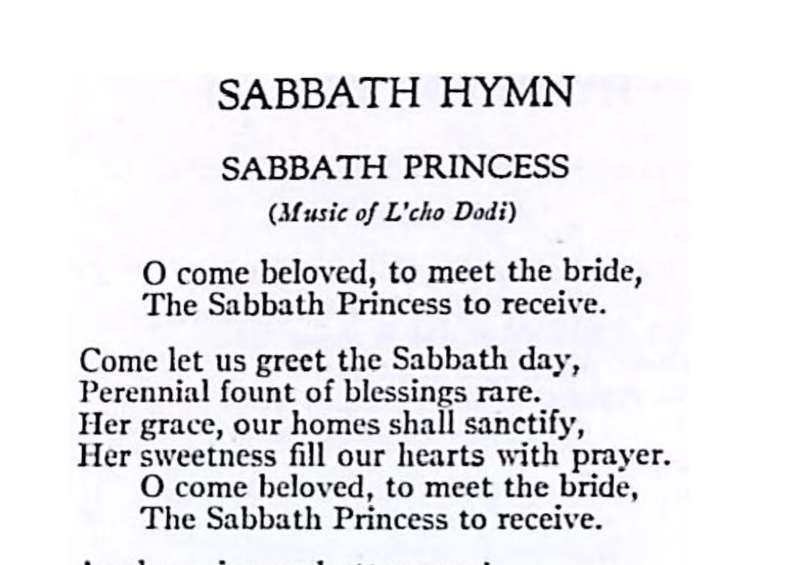

To himself he trills and murmurs, Till at last his voice he raises: Till he sings with joy resounding, “Lecho dodi likrath kallah!” |

Lecho Daudi Likras Kalle – Komm’, Geliebter, deiner harret Schon die Braut, die dir entschleiert Ihr verschämtes Angesicht! |

“Lecho dodi likrath kallah — Come, beloved one, the bride Waits already to uncover To thine eyes her blushing face!” |

Dieses hübsche Hochzeitcarmen Ist gedichtet von dem großen, Hochberühmten Minnesinger Don Jehuda ben Halevy. |

The composer of this poem. Of this pretty marriage song, Is the famous paytan, Don Jehuda ben Halevy.[1] The composer of the popular piyyut for welcoming the Shabbat, “Lekha Dodi,” was actually Shlomo ha-Levi Alkabetz, also spelt Alqabitz, Alqabes; (Hebrew: שלמה אלקבץ) (ca. 1500 – 1576), a rabbi, kabbalist and poet perhaps best known for his composition of Lekha Dodi. While there are variations by other paytanim, Judah Halevi (ca. 1075 – 1141) was not one of them. –Aharon Varady |

In dem Liede wird gefeiert Die Vermählung Israels Mit der Frau Prinzessin Sabbath, Die man nennt die stille Fürstin. |

It was writ by him in honour Of the wedding of Prince Israel And the gentle Princess Shabbat, Whom they call the silent princess. |

Perl’ und Blume aller Schönheit Ist die Fürstin. Schöner war Nicht die Königin von Saba, Salomonis Busenfreundin, |

Pearl and flower of all beauty Is the princess — not more lovely Was the famous Queen of Sheba, Bosom friend of Solomon, |

Die, ein Blaustrumpf Aethiopiens, Durch Esprit brilliren wollte, Und mit ihren klugen Räthseln Auf die Länge fatigant ward. |

Who, bas bleu of Ethiopia, Sought by wit to shine and dazzle. And became at length fatiguing With her very clever riddles. |

Die Prinzessin Sabbath, welche Ja die personifizirte Ruhe ist, verabscheut alle Geisteskämpfe und Debatten. |

Princess Shabbat, rest incarnate, Held in hearty detestation Every form of witty warfare And of intellectual combat. |

Gleich fatal ist ihr die trampelnd Declamirende Passion, Jenes Pathos, das mit flatternd Aufgelöstem Haar einherstürmt. |

She abhorred with equal loathing Loud declamatory passion — Pathos ranting round and storming With dishevelled hair and streaming. |

Sittsam birgt die stille Fürstin In der Haube ihre Zöpfe; Blickt so sanft wie die Gazelle, Blüht so schlank wie eine Addas. |

In her cap the silent princess Hides her modest, braided tresses, Like the meek gazelle she gazes. Blooms as slender as the myrtle. |

Sie erlaubt dem Liebsten alles, Ausgenommen Tabakrauchen – „Liebster! rauchen ist verboten, Weil es heute Sabbath ist. |

She denies her lover nothing Save the smoking of tobacco; “Dearest, smoking is forbidden, For today it is the Sabbath. |

„Dafür aber heute Mittag Soll dir dampfen, zum Ersatz, Ein Gericht, das wahrhaft göttlich – Heute sollst du Schalet essen!” |

“But at noon, as compensation. There shall steam for thee a dish That in very truth divine is — Thou shalt eat today of cholent! |

Schalet, schöner Götterfunken, Tochter aus Elysium! Also klänge Schiller’s Hochlied, Hätt’ er Schalet je gekostet. |

“Cholent, ray of light immortal! Cholent, daughter of Elysium!” So had Schiller’s song resounded, Had he ever tasted Cholent. |

Schalet ist die Himmelspeise, Die der liebe Herrgott selber Einst den Moses kochen lehrte Auf dem Berge Sinai, |

For this cholent is the very Food of heaven, which, on Sinai, God Himself instructed Moses In the secret of preparing, |

Wo der Allerhöchste gleichfalls All die guten Glaubenslehren Und die heil’gen zehn Gebote Wetterleuchtend offenbarte. |

At the time He also taught him And revealed in flames of lightning All the doctrines good and pious. And the holy Ten Commandments. |

Schalet ist des wahren Gottes Koscheres Ambrosia, Wonnebrod des Paradieses, Und mit solcher Kost verglichen |

Yes, this cholent’s pure ambrosia Of the true and only God: Paradisal bread of rapture; And, with such a food compared, |

Ist nur eitel Teufelsdreck Das Ambrosia der falschen Heidengötter Griechenlands, Die verkappte Teufel waren. |

The ambrosia of the pagan. False divinities of Greece, Who were devils ‘neath disguises, Is the merest devils’ offal. |

Speist der Prinz von solcher Speise, Glänzt sein Auge wie verkläret, Und er knöpfet auf die Weste, Und er spricht mit sel’gem Lächeln: |

When the prince enjoys the dainty. Glow his eyes as if transfigured, And his waistcoat he unbuttons; Smiling blissfully he murmurs, |

„Hör’ ich nicht den Jordan rauschen? Sind das nicht die Brüßelbrunnen In dem Palmenthal von Beth-El, Wo gelagert die Kameele? |

“Are not those the waves of Jordan That I hear — the flowing fountains In the palmy vale of Beth-El, Where the camels lie at rest? |

„Hör ich nicht die Heerdenglöckchen? Sind das nicht die fetten Hämmel, Die vom Gileath-Gebirge Abendlich der Hirt herabtreibt?“ |

“Are not those the sheep-bells ringing Of the fat and thriving wethers That the shepherd drives at evening Down Mount Gilead from the pastures?” |

Doch der schöne Tage verflittert; Wie mit langen Schattenbeinen Kommt geschritten der Verwünschung Böse Stund’ – es seufzt der Prinz. |

But the lovely day flits onward, And with long, swift legs of shadow Comes the evil hour of magic — And the prince begins to sigh; |

Ist ihm doch als griffen eiskalt Hexenfinger in sein Herze. Schon durchrieseln ihn die Schauer Hündischer Metamorphose. |

Seems to feel the icy fingers Of a witch upon his heart; Shudders, fearful of the canine Metamorphosis that waits him. |

Die Prinzessin reicht dem Prinzen Ihre güldne Nardenbüchse. Langsam riecht er – Will sich laben Noch einmal an Wohlgerüchen. |

Then the princess hands her golden Box of spikenard to her lover, Who inhales it, fain to revel Once again in pleasant odours. |

Es kredenzet die Prinzessin Auch den Abschiedstrunk dem Prinzen – Hastig trinkt er, und im Becher Bleiben wen’ge Tropfen nur. |

And the princess tastes and offers Next the cup of parting also — And he drinks in haste, till only Drops a few are in the goblet. |

Er besprengt damit den Tisch, Nimmt alsdann ein kleines Wachslicht, Und er tunkt es in die Nässe, Daß es knistert und erlischt. |

These he sprinkles on the table. Then he takes a little wax-light, And he dips it in the moisture Till it crackles and is quenched. |

“Prinzessin Sabbat” by Heinrich Heine, in Romanzero III: Hebraeische Melodien, (“Princess Shabbat,” in Romanzero III, Hebrew Melodies.), 1851 was translated into English by Margaret Armour (1860-1943), The Works of Heinrich Heine vol. 12: Romancero: Book III, Last Poems (1905). I have replaced “schalet” (unchanged in Armour’s translation) with cholent and made other subtle changes (‘kiss your holy mezuzot’ instead of ‘kiss your holy door-posts,’ etc.). –Aharon Varady

Source

Notes

| 1 | The composer of the popular piyyut for welcoming the Shabbat, “Lekha Dodi,” was actually Shlomo ha-Levi Alkabetz, also spelt Alqabitz, Alqabes; (Hebrew: שלמה אלקבץ) (ca. 1500 – 1576), a rabbi, kabbalist and poet perhaps best known for his composition of Lekha Dodi. While there are variations by other paytanim, Judah Halevi (ca. 1075 – 1141) was not one of them. –Aharon Varady |

|---|

“Prinzessin Sabbat | Princess Shabbat, by Heinrich Heine (1851)” is shared through the Open Siddur Project with a Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication 1.0 Universal license.

Leave a Reply