| Source (Hebrew) | Translation (English) |

|---|---|

מִי כָמוֹךָ דֵּעָה מוֹרֶה נִיב שְׂפָתַיִם אַתָּה בוֹרֵא מַחְשְׁבוֹתֶיךָ עָמְקוּ וְרָמוּ וּשְׁנוֹתֶיךָ לֹא יִתָּמּוּ לֹא לִמְּדוּךָ חָכְמָתֶךָ וְלֹא הֱבִינוּךָ תְּבוּנָתֶךָ |

Who is like unto you who teaches knowledge and creates the fruit of the lips? Your purposes are deep and exalted, and your years have no end. None taught you your wisdom nor imparted to you your understanding. |

לֹא קִבַּלְתָּ מַלְכוּתֶךָ וְלֹא יָרַשְׁתָּ מֶמְשַׁלְתֶּךָ לְעוֹלָם יְהִי לְךָ לְבַדֶּךָ וְלֹא לַאֲחֵרִים כְּבוֹד הוֹדֶךָ וְלֹא תִּתֵּן לֵאלֹהִים אֲחֵרִים תְּהִלָּתְךָ לֹא לַפְּסִילִים וְזָרִים וְכָבוֹד וְגַם כׇּל יָקָר מֵאִתָּךְ וּכְבוֹדְךָ לֹא לְזָרִים אִתָּךְ |

You did not succeed to your kingdom, nor inherit your dominion. For all time shall the glory of your majesty be yours alone and unshared by others; For you will not yield of your praise unto other gods, unto graven images and idols. Glory and honour proceed from you, idols shall not share them with you. |

אַתָּה תָּעִיד בְּיִחוּדֶךָ וְתוֹרָתְךָ לַעֲבָדֶיךָ אֱלֹהֵינוּ עַל יִחוּדֶךָ אַתָּה עֵד אֱמֶת וַאֲנַחְנוּ עֲבָדֶיךָ |

Your Unity is declared by you, by your law and by your servants; Yea, O our God, to your Unity you are yourself a faithful witness, and we your servants. |

לְפָנֶיךָ לֹא אֵל הִקְדִּימָךְ וּבִמְלַאכְתְּךָ לֹא הָיָה אֵל עִמָּךְ וְלֹא נוֹעַצְתָּ וְלֹא לֻמַּדְתָּ בְּחַדֶּשְׁךָ בְּרִיאוֹת כִּי נְבוּנוֹתָ מִמַּעֲמַקֵּי מַחְשְׁבוֹתֶיךָ אֵין רֹאשׁ וָסוֹף לִתְבוּנָתֶךָ |

No god preceded you, and there was no stranger with you in your work. You were not counselled, nor instructed when you made all things new; for understanding is yours. From the depths of your mind and from your own heart you conceived all your works. |

קְצוֹת דְּרָכֶיךָ הֲלֹא הִכַּרְנוּ מִמַּעֲשֶׂיךָ הֵן יָדַעְנוּ שָׁאַתָּה אֵל כֹּל יָצַרְתָּ לְבַדֶּךָ מֵאָז לֹא נִגְרַעְתָּ וְלַעֲשׂוֹת מְלַאכְתֶּךָ לֹא לֻחַצְתָּ וְגַם בַּעַדְךָ לֹא נִצְרָכְתָּ כִּי הָיִיתָ לִפְנֵי הַכֹּל וְאָז בְּאֵין כֹּל לֹא נִצְרַכְתָּ כֹּל כִּי מֵאַהֲבָתְךָ עֲבָדֶיךָ כֹּל בָּרָאתָ לִכְבוֹדֶךָ |

Have we not discerned a little portion of your ways? Lo! we have learnt from your works That you are the God who unaided created everything, yourself undiminished. You were not compelled to perform your work, and had no need of a helper. Yea, you were before all, and needed naught when naught existed. For from your love to your servants, you created the whole world unto your glory. |

וְלֹא נוֹדַע אֵל זוּלָתֶךָ וְאֵין כָּמוֹךָ וְאֵין בִּלְתֶּךָ וְלֹא נִשְׁמַע מִן אָז וָהָלְאָה וְלֹא קָם וְלֹא נִהְיָה וְלֹא נִרְאָה וְגַם אַחֲרֶיךָ לֹא יִהְיֶה אֵל רִאשׁוֹן וְאַחֲרוֹן אֵל יִשְׂרָאֵל בָּרוּךְ אַתָּה יָחִיד וּמְיֻחָד יְיָ אֶחָד וּשְׁמוֹ אֶחָד |

No god save you is known, none like you, none beside you; Nor ever has arisen or existed, or been heard or seen; Nor after you shall there be any god. First and last is the God of Yisrael. Blessed are you, O one and only Hashem is one and Their Name is one. |

אֲשֶׁר מִי יַעֲשֶׂה כִּמְלַאכְתֶּךָ כְּמַעֲשֶׂיךָ וְכִגְבוּרוֹתֶיךָ אֵין יְצִיר זוּלַת יְצִירָתֶךָ אֵין בְּרִיאָה כִּי אִם בְּרִיאָתֶךָ כׇּל אֲשֶׁר תַּחְפֹּץ תַּעֲשֶׂה בַכֹּל כִּי אַתָּה נַעֲלֵיתָ עַל כֹּל אֵין כָּמוֹךָ וְאֵין בִּלְתֶּךָ כִּי אֵין אֱלֹהִים זוּלָתָךָ אַתָּה הָאֵל עוֹשֵׂה פֶלֶא וְדָבָר מִמְּךָ לֹא יִפָּלֵא |

For who can do like unto your works, your deeds, your mighty actions? There is no form save of your forming, no creature save of your creation. You work your pleasure over all, for you are exalted above all. Yea, there is none like you and none beside you, for there is no god save you. You are El who perform marvels, but unto whom naught is marvellous. |

מִי כָמוֹךָ נוֹרָא תְּהִלּוֹת אֱלֹהִים לְבַדְּךָ עוֹשֶׂה גְדוֹלוֹת אֵין אוֹתוֹת כְּמוֹ אוֹתוֹתֶיךָ אַף אֵין מוֹפֵת כְּמוֹ מוֹפְתֶיךָ אֵין תְּבוּנָה כִּתְבוּנָתֶךָ אֵין גְּדֻלָּה כִּגְדֻלָּתֶךָ כִּי מְאֹד עָמְקוּ מַחְשְׁבוֹתֶיךָ וְגָבְהוּ דַּרְכֵי אֹרְחוֹתֶיךָ |

Who is like unto you, tremendous in praise, O Elohim who alone works wonders? There are no signs like your signs, no portents like your portents; There is no knowledge like your knowledge, no greatness like your greatness. For your purposes are very deep, and the paths of your treading are very lofty. |

אֵין גַּאֲוָה כְּמוֹ גַאֲוָתֶךָ אַף אֵין עֲנָוָה כְּעַנְוָתֶךָ אֵין קְדֻשָּׁה כִּקְדֻשָּׁתֶךָ אֵין קְרֵבוּת כְּמוֹ קְרֵבוּתֶךָ אֵין צְדָקָה כְּצִדְקָתֶךָ אֵין תְּשׁוּעָה כִּתְשׁוּעָתֶךָ אֵין זְרוֹעַ כִּזְרֵעוֹתֶיךָ אֵין קוֹל כְּרַעַם גְּבוּרוֹתֶיךָ אֵין רַחֲמִים כְּרַחֲמָנוּתֶךָ אֵין חֲנִינָה כַּחֲנִינוּתֶךָ אֵין אֱלֹהוּת כֵּאלֹהוּתֶךָ אֵין מַפְלִיא כְּשֵׁם תִּפְאַרְתֶּךָ כִּי שְׁמוֹתֶיךָ אֵלִים מְרוּצִים בְּזֳכְרְךָ לְחוּצִים לְהַפְלִיא נְחוּצִים |

There is no majesty like your majesty, yea, and there is no gentleness like your gentleness; No holiness like your holiness, no nearness like nearness to you; No righteousness like your righteousness, no salvation like your salvation; No strength like your strength, no sound like the thunder of your might. There is no mercy like your mercy, and no grace like your graciousness. There is no divinity like your divinity, and naught full of wonders like your glorious Name. For your [divine] names are swift angels who speed upon your miracles, when you remember the oppressed. |

וְאַשָּׁף וְחַרְטֹם לֹא יְלַחֲצוּךָ וְכׇל־שֵׁם וְלַהַט לֹא יְנַצְּחוּךָ לֹא יְנַצְּחוּךָ כׇּל הַחֲכָמִים כׇּל הַקּוֹסְמִים וְהַחַרְטֻמִּים אַתָּה מֵשִׁיב לְאָחוֹר חֲכָמִים לֹא יוּכְלוּ לְךָ עֲרוּמִים וְקוֹסְמִים לְהָשִׁיב לְאָחוֹר מְזִּמּוֹתֶיךָ לְהָפֵר עֲצַת סוֹד גְּזֵרוֹתֶיךָ מֵרְצוֹנְךָ לֹא יַעֲבִירוּךָ לֹא יְמַהֲרוּךָ וְלֹא יְאַחֲרוּךָ |

No enchanter or magician can compel you, no spell or sorcery can prevail against you. Not all the wizards, the enchanters and magicians can avail against you. You turn the wizards back, and the subtle enchanters strive in vain To annul your designs, to frustrate the purpose of your secret decree. From your will they cannot move you, nor hasten you, nor delay you. |

עֲצָתְךָ תָּפֵר עֲצַת כׇּל יוֹעֲצִים וְעֻזְּךָ מַחֲלִישׁ לֵב אַמִּיצִים אַתָּה מְצַוֶּה וּפַחְדְּךָ מַשְׁוֶה וְאֵין עָלֶיךָ פָּקִיד מְצַוֶּה אַתָּה מִקְוֶה וְאֵינְךָ מְקַוֶּה לְךָ כׇּל מְקַוֶּה נֶפֶשׁ תִּרְוֶה וְכׇל הַיְצוּרִים וְכׇל עִנְיָנָם וְכׇל יְקָר אֲשֶׁר בְּךָ אֵין דִּמְיוֹנָם לֹא מַחְשְׁבוֹתָם מַחְשְׁבוֹתֶיךָ כִּי אֵין בּוֹרֵא זוּלָתֶךָ |

For your counsel frustrates the counsel of all counsellors, and your strength dissolves the heart of the mighty. You command, and your terror levels all before you, but over you lies no directing power. You know not hope, who are the Hope of the world, and in whom every soul that hopes is satisfied. Among all your manifold creatures there is naught to compare with your great majesty. Their thoughts are not your thoughts, for there is no creator beside you. |

לְאֵין דִּמְיוֹן נִפְלָא אֱלֹהֵינוּ וְאֵין חֵקֶר נִשְׂגָּב אֲדֹנֵנוּ סָתוּר מִכׇּל סָתוּר וְעָמוּס מִכׇּל עָמוּס וּמִכׇּל כָּמוּס דַּק מִכׇּל דַּק וּצְפוּן מִכֹּל צָפוּן וְיָכוֹל מִכׇּל יָכוֹל נִשְׂגָּב מִכׇּל נִשְׂגָּב וְנֶעֱלָם מִכׇּל נֶעֱלָם וּשְׁמוֹ לְעוֹלָם גָּבוֹהַּ מִכׇּל גָּבוֹהַּ וְעֶלְיוֹן מִכׇּל עֶלְיוֹן וּמִכׇּל חֶבְיוֹן חָבוּי וְעָמוּק מִכׇּל עָמוּק לֵב כׇּל דַּעַת עָלָיו חָמוּק |

Our Elo’ah is wondrous beyond compare, yea, our Lord is exalted past conception; More hidden than aught that is hidden or stored up or treasured, Finer than the finest substance, invisible of the invisible, mightiest of the mighty. Highest are They of the high, and most impenetrable; Their Name also is eternal. They are loftier than the loftiest, greater than the greatest; most mysterious Of all that is mysterious; They are unsearchable above all else, and the heart of all knowledge centres about Them. |

שֶׁאֵין שֵׂכֶל וּמַדָּע וְחָכְמָה יְכוֹלִים לְהַשְׁווֹת לוֹ כׇּל מְאוּמָה לֹא מַשִּׂיגִים לוֹ אֵיךְ וְכַמֶּה לֹא מוֹצְאִים לוֹ דָּבָר דּוֹמֶה מִקְרֶה וְעַרְעַר וְשִׁנוּי וְטָפֵל וְחֶבֶר וּמִסְמָךְ אוֹר וְגַם אֹפֶל לֹא מוֹצְאִים לוֹ מַרְאֶה וְצֶבַע וְלֹא כׇל טֶבַע אֲשֶׁר שֵׁשׁ וָשֶׁבַע |

For no understanding, no wit, no wisdom can bring aught to compare with Them. For these cannot predicate manner or quantity of Them; they cannot find analogy to Them, Nor any chance or accident, association or combination, light or darkness. They cannot find in Them form or colour nor any corporeal property. |

לָכֵן נְבוּכוֹת כׇּל עֶשְׁתּוֹנוֹת וְנִבְהָלוֹת כׇּל הַחֶשְׁבּוֹנוֹת וְכׇל שַׂרְעַפִּים וְכׇל הַרְהוֹרִים נִלְאִים לָשׁוּם בּוֹ שִׁעוּרִים מִלְּשַׁעֲרֵהוּ וּמִלְּהַגְבִּילֵהוּ מִלְּתָּאֲרֵהוּ וּמִלְּפַרְסְמֵהוּ בְּכׇל שִׂכְלֵנוּ חִפַּשְׂנוּהוּ בְּמַדָּעֵנוּ לִמְצֹא מַה הוּא לֹא מְצָאנוּהוּ וְלֹא יְדַעְנוּהוּ אַךְ מִמַּעֲשָׂיו הִכַּרְנוּהוּ שֶׁהוּא לְבַדּוֹ יוֹצֵר אֶחָד חַי וְכֹל יוּכַל וְחָכָם מְיֻחָד כִּי הוּא הָיָה לַכֹּל קוֹדֵם עַל כֵּן נִקְרָא אֱלֹהֵי קֶדֶם |

Wherefore every investigation of Them is baffled, and every calculation is confounded. All thoughts and all reflections weary themselves to find terms for Them, To estimate Them, to delimit Them, to delineate Them, to reveal Them. Though with all our wit and mind we have searched to discover what They are. Yet we have not found Them nor known Them. Howbeit from Their works we recognize and learn That They are the sole Creator, Living, Omnipotent, and All-wise; That They are older than aught, wherefore They are called the God of old. |

בַּעֲשׂוֹתוֹ בְּלִי כׇל מְאוּם אֶת כֹּל יָדַעְנוּ כִּי הוּא כֹּל יָכוֹל בַּאֲשֶׁר מַעֲשָׂיו בְּחָכְמָה כֻלָּם יָדַעְנוּ כִּי בְּבִינָה פְּעָלָם בְּכׇל יוֹם וָיוֹם בְּחַדְּשׁוֹ כֻלָּם יָדַעְנוּ כִּי הוּא אֱלֹהֵי עוֹלָם בַּאֲשֶׁר הָיָה קֹדֶם לְכֻלָּם יָדַעְנוּ כִּי הוּא חַי לְעוֹלָם |

Forasmuch as They made everything from nothing, we know that They are almighty. Forasmuch as all Their works are wise, we know that They fashioned them with understanding. As day by day They renew them all, we know that They are elo’ah of the world; And since They existed before any of them, we know that They are living and everlasting. |

וְאֵין לְהַרְהֵר אַחַר יוֹצְרֵנוּ בְּלִבֵּנוּ וְלֹא בְסִפּוּרֵנוּ לְמֵמָּשׁ וְגֹדֶשׁ לֹא נְשַׁעֲרֵהוּ לְטַפֵל וְתֹאַר לֹא נְדַמֵּהוּ וְלֹא נְחַשְּׁבֵהוּ לְעִקָּר וְנִצָּב וְלֹא לְמִין וְכׇל אוֹן וּלְכׇל נִקְצָב |

Therefore we may not attempt to reason of our Creator by thought or speech. We may not class Them with matter or substance, or ascribe to Them accident or attribute. We may not think of Them as of root or stem, as genus or species, or as in any wise limited. |

כׇּל הַנִּרְאִים וְהַנִּשְׂכָּלִים וְהַמַּדָּעִים בְּעֶשֶׂר כְּלוּלִים וְשֶׁבַע כַּמָּיוֹת וְשֵׁשֶׁת נִדּוֹת וְשָׁלֹשׁ גְּזֵרוֹת וְעִתּוֹת וּמִדּוֹת הֵן בַּבּוֹרֵא אֵין גַּם אֶחָד כִּי הוּא בְּרָאָם כֻּלָּם כְּאֶחָד כֻּלָּם יִבְלוּ וְאַף יַחֲלֹופוּ הֵם יֹאבְדוּ וְאַף יָסוּפוּ וְאַתָּה תַעֲמֹד וּתְבַלֶּה כֻּלָּם כִּי חַי וְקַיָּם אַתָּה לְעוֹלָם׃ |

All things that are seen or conceived or known are included in the ten categories.[1] In ten categories. — The enumeration here given belongs to Jewish mediaeval philosophy. The ten categories are mentioned by Saadyah, who lived from 892-942 C.E., and were taken by him from Aristotle. They are:—substance (οὐσία, ousia), quantity (ποσόν, poson), quality (ποιόν, poion), relation (πρός τι, pros ti), place (ποῦ, pou), time (πότε, pote), position (κεῖσθαι, keisthei), possession (ἔχειν, echein), activity (ποιεῖν, poiein), and passivity (πάσχειν, paschein). There are seven kinds of quantity[2] The seven quantities are not to be found in Aristotle, but appear to be borrowed from the philosopher Ibn Rashid (Averrhoes). and six kinds of motion,[3] The six kinds of motion (Aristotle, Categories, 14,1) are :—creation (γένεσις, genesis), destruction (φθορά, phthora), growth (αὔξησις, auxésis), diminution (µείωσις, meíōsis), transformation (ἀλλοίωσις, alloíosis), and change of place (κατὰ τόπον µεταβολή, katá tópon metabállō). three modes of predication,[4] The three modes of predication are: by characteristic, by property, and by accident. three times,[5] The three times are: the present, the past, and the future. and three dimensions.[6] The three dimensions are: length, breadth and depth. Lo! in the Creator not one of them exists, for They created them all together. They shall all wither and pass away, yea, they shall perish and be no more. But you will abide and see them all to fade, for you live and endure to all eternity. |

This is the shir ha-yiḥud l’yom ḥamishi (hymn of unity for the fifth day), adapted from the translation by Herbert M. Adler and published in the maḥzor for Rosh ha-Shanah by Adler and Arthur Davis (1907), pp. 53-56. I have made changes to the translation, mainly to update archaic language but also, sparingly, elsewhere. (If you find a phrasing which, opposite the Hebrew, should definitely be revised: please suggest a revision.) I’ve also replaced male default language for God with gender inclusive terms. The transcription of the shir published here is based first on the unvocalized text found in Lia van Aalsum’s dissertation, “Lied van de eenheid. Een onderzoek naar de bijbelse intertekstualiteit van het spirituele geschrift Sjier haJichoed” (2010), pp. 55-58. Dr. Van Aalsum’s transcription was itself derived from the published transcription of Abraham Meir Habermann (Mosad haRav Kook: 1948), pp. 34-40. I have vocalized the text according to A.M. Habermann’s work. –Aharon Varady

In his introduction to a facsimile edition of the first printing of the Shir haYiḥud (Thiengen 1560) published by Joseph Dan in 1981, Dan writes:

“Shir ha-Yiḥud”, “The Hymn of Divine Unity”, is a theological poem, composed in Central Europe in the second half of the 12th century by a Jewish theologian or mystic who probably belonged to the sect of the Ashkenazi Ḥasidim (Jewish-German Pietists). This poem became one of the most famous poetic works to be included in the Jewish prayer-book, and had great impact upon the development of theological poetry in Hebrew. To some extent it can be compared to the famous “Keter Malchut” by Rabbi Shlomo ben Gevirol; both poems gave expression to the deepest religious attitudes found in the Jewish cultures which created them.

“Shir ha-Yiḥud” is an anonymous poem, even though some editions, including the one reproduced here, attribute it to the leader of the Ashkenazi Ḥasidic movement, Rabbi Judah ben Samuel the Pious, who lived in Spyer and Regensburg in the second half of the 12th century and the beginning of the 13th (died in 1217). In one of the esoteric theological works of Rabbi Judah, written circa 1200, this poem is quoted, and attributed to a “poet”, as if it were an old, well-known work of liturgy (Ms. Oxford 1567, 4b-5a). This could be seen as conclusive evidence that Rabbi Judah did not write this poem, for an author does not, usually, quote his own work in this way. However, the possibility that Rabbi Judah was the author should not be rejected off-hand. It is a fact that Rabbi Judah insisted, in his ethical works, that books and hymns shouid be published anonymously, for the inclusion of the author’s name in them might cause his descendants to commit the sin of pride. We do not have works by Rabbi Judah signed by him, and it seems that he himself scrupulously observed this maxim, though even his closest disciple, Rabbi Eleazar of Worms, did sign all his work in his full name. In the same theological treatise Rabbi Judah quoted “Sefer Ḥasidim”’, his major ethical work, several times, as an anonymous work. However, we do lack a positive indication that proves him to be the author. It seems that by the thirties of the 13th century no clear tradition existed in Germany concerning the authorship of the hymn. In Rabbi Moses Taku’s polemical work, “Ketav Tamim”, the hymn is mentioned twice and attributed to “Rabbi Bezalel and Rabbi Samuel’, and it is evident that Rabbi Moses did not know anything about the author of the work.

The theology of the Shir ha-Yiḥud is based to a very large extent on the text of Rav Saadia Gaon’s Book of Beliefs and Ideas, but not on the original text (in Arabic) or the standard 12th century translation by Rabbi Judah ben Tibbon, but on an early paraphrase of the work, probably made in the 11th century. This paraphrase transformed Rav Saadia’s philosophical treatise into a poetic description of God’s greatness, and several passages of such descriptions were included in the “Shir ha-Yiḥud” almost verbatim. The author in medieval Germany used Saadia’s material to introduce to his own community some basic concepts concerning the creation and the nature of God, emphasizing his remoteness from any corporeal description and insisting especially on the divine immanence throughout the cosmos. Rabbi Moses Taku’s criticism of the work concentrated on this aspect of the hymn’s theology, for Rabbi Moses objected to the new, philosophical attitude towards God which began to spread in the Jewish community in Germany at that time, mainly through the teachings of the Ashkenazi Ḥasidim.

The Shir ha-Yiḥud is the first step in the evolvement of a whole literary genre, which developed in Germany in the 13th century and produced nearly a score of treatises, most of them including the term “Yiḥud” (divine unity) in their titles. These works, written by the Ashkenazi Hasidim, popularized the theology influenced by Saadia, insisting on divine transcendence and immanence at the same time, rejecting anthropomorphic concepts of God and explaining divine revelation in non-corporeal terms. These works were written in prose, leaving Shir ha-Yiḥud as one of the very few examples of Jewish theology of this period expressed in poetic form. One more example, however, is published here — a theological poem which was written in a circle of Jewish mystics late in the 12th century, which was included in several works, among them those of Rabbi Elhanan ben Yaqar of London (middle of the 13th century). This poem was probably written in order to serve as a basis for a theological exegesis, for, unlike Shir ha-Yihud, it is brief and cryptic. These two examples serve, however, to demonstrate the role that poetry played in the emergence of Jewish esoteric and mystical literature in Central Europe.

Source(s)

Notes

| 1 | In ten categories. — The enumeration here given belongs to Jewish mediaeval philosophy. The ten categories are mentioned by Saadyah, who lived from 892-942 C.E., and were taken by him from Aristotle. They are:—substance (οὐσία, ousia), quantity (ποσόν, poson), quality (ποιόν, poion), relation (πρός τι, pros ti), place (ποῦ, pou), time (πότε, pote), position (κεῖσθαι, keisthei), possession (ἔχειν, echein), activity (ποιεῖν, poiein), and passivity (πάσχειν, paschein). |

|---|---|

| 2 | The seven quantities are not to be found in Aristotle, but appear to be borrowed from the philosopher Ibn Rashid (Averrhoes). |

| 3 | The six kinds of motion (Aristotle, Categories, 14,1) are :—creation (γένεσις, genesis), destruction (φθορά, phthora), growth (αὔξησις, auxésis), diminution (µείωσις, meíōsis), transformation (ἀλλοίωσις, alloíosis), and change of place (κατὰ τόπον µεταβολή, katá tópon metabállō). |

| 4 | The three modes of predication are: by characteristic, by property, and by accident. |

| 5 | The three times are: the present, the past, and the future. |

| 6 | The three dimensions are: length, breadth and depth. |

“שִׁיר הַיִּחוּד לְיוֹם חֲמִישִׁי | Hymn of Divine Unity for the Fifth Day, by an unknown paytan (ca. 12th c.)” is shared through the Open Siddur Project with a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International copyleft license.

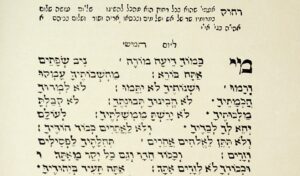

![Shir haYihud l'Yom Sheni (Thiengen 1560 [facsimile]), p. 7 - crop](https://opensiddur.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/shir-hayihud-lyom-sheni-thiengen-1560-facsimile-p--7-crop-250x250.jpg)

![Shir haYihud l'Yom Shlishi (Thiengen 1560 [facsimile]), p. 11 - crop](https://opensiddur.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/shir-hayihud-lyom-shlishi-thiengen-1560-facsimile-p--11-crop-250x250.jpg)

![Shir haYihud l'Yom Rishon (Thiengen 1560 [facsimile]), p. 3 - crop](https://opensiddur.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/shir-hayihud-lyom-rishon-thiengen-1560-facsimile-p--3-crop-250x250.jpg)

![Shir haYihud l'Yom Revi'i (Thiengen 1560 [facsimile]), p. 18 - crop](https://opensiddur.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/shir-hayihud-lyom-revii-thiengen-1560-facsimile-p--18-crop-250x250.jpg)

Leave a Reply