1.396263401595464

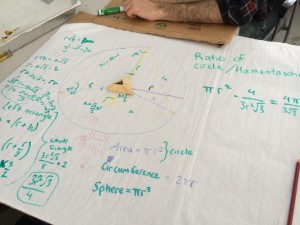

Ratio of a circle of dough to an equilateral triangle hamentashen. Happy pi day!

(image and general brilliance credit to Sarah Chandler!)

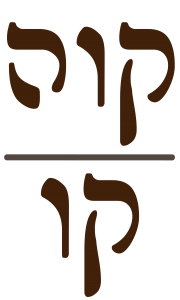

“It is interesting to check whether more precise values were known to the ancient Hebrews. The answer to this may be found in the Hebrew Bible.[1] Matityahu Hacohen Munk, “Three Geometric Problems in the Bible and the Talmud,” Sinai 51 (1962), 218-227. [in Hebrew] ;[2] ibid, “The Halachic Way in Solving Special Geometric Problems,” Hadarom 27 (1968), 115133. [in Hebrew] There is a Rabbinical tradition on the reading-versus-writing disparity in I Kings 7:23. According to Hebrew scriptural tradition, the word meaning ‘line’ is written as קוה, but read as קו…” –from “On the Rabbinical Approximation of Pi” by Boaz Tsaban and David Garber

ON THE RABBINICAL APPROXIMATION OF π

BOAZ TSABAN AND DAVID GARBER, tsaban@macs.biu.ac.il, garber@macs.bin.ac.il

Department of Mathematics, Bar-Ilan University, 52900 Ramat-Gan, Israel,

Abstract.

We discuss the Rabbinical tradition of geometry concerning circular shapes, as it appears in the Babylonian Talmud and in later commentaries. Three explanations of the difference between π and the Rabbinical value for it, so far not widely known among the scientific community, are given.

Nous discutons ici la tradition rabbinique en geometrie a propos des figures cir culaires, telle qu elle apparait dans le Talmud Babylonien et dans des commentaires ulterieurs. Trois explications sont proposees sur la difference entre π et la valeur donnee dans la litteratu re rabbinique. Ces explications semblent peu connues dans la communaute scientifique.

Wir diskutieren die rabbinische Tradition der Geometrie der kreisformigen For men, wie sie im babylonischen Talmud und in spateren Kommentaren erscheint. Wir geben drei Erklarungen fur den Unterschied zwischen π und seinem rabbinis chen Wert, die unter Wissenschaftlern noch nicht weit bekannt sind.

MSC 1991 subject classifications: 01A35, 01A17.

KEY WORDS: Nonstandard Geometry, History of Pi, Jewish Mathematics.

1. Introduction

The Talmud, which literally means study, is a monumental Hebrew work consisting of knowledge accumulated over thousands of years through extensive study by Jewish scholars. The Talmud consists of two portions: the Mishna and the Gemara. The teaching contained in the former was transmitted from generation to generation by word of mouth, and finally compiled and edited by Rabbi Yehuda Hanasi (the President) at the end of the second century CE. It is divided into six sections, each divided into tractates (or treatises) which are sub divided into chapters. Each chapter is divided into paragraphs.[3] Thus, e.g., Mishna Ohalot X II 6 means: Mishna, tractate Ohalot, chapter X II, sixth paragraph (tractate Ohalot is in section Teharot, bu t the section is usually omitted). The Gemara consists of discussions and disputations on the Mishna. This induces a division of the Talmud, according to the tractates of the Mishna. Those taking part in the discussions are called Amoraim (singular: Amora), meaning tellers or interpreters. It is common to say ‘The Gemara’ (says, asks, etc.) when referring to an anonymous Amora who is quoted in the Gemara. There are two schools of Amoraim: the Babylonian and the Palestinian. Each school compiled its own Talmud: the Babylonian Talmud and the Palestinian (or Jerusalem) Talmud, respectively.

Small portions of the Babylonian Talmud began to be published soon after the introduction of printing. The first complete Talmud[4] Unless otherwise indicated, Talmud always refers to the Babylonian Talmud. was printed by Daniel Bomberg in Venice between 1520-1523 CE. This editio princeps determined the external form of the Talmud for all time, including the pagination and the running commentaries of Rashi[5] Rashi is the acronym of Rabbi Shlomo Itshaqi of Troyes (1040-1105 CE). and the Tosafot.[6] The word Tosafot means addendas. This commentary was written mainly by Rashi’s sons-in-law and grandsons during the 12th and 13th centuries CE. In this printing, the Talmud is divided into folios, each of which consists of two pages.[7] Thus, e.g., Talmud Suca 8a means: (Babylonian) Talmud, tractate Suca, folio number 8, first page. The Palestinian Talmud, on the other hand, is referred to by the tractate, the chapter, and the paragraph number. Palestinian Talmud, Rosh Hashana 2:6 thus refers to the sixth paragraph of the second chapter in tractate Rosh Hashana of the Palestinian Talmud. The best known among more modern editions of the Talmud is the one printed in Vilna by the widow and the brothers of the printer Romm in 1880 CE. This edition is still the most popular edition among Jewish Talmud scholars.[8] A good reference on the Talmud is [12, 15: 750-779].

Rabbi Yohanan Ben Nappaha (“son of the blacksmith”) (ca.180-ca.279 CE) is one of the greatest Amoraim. Rabbi Yohanan lived in Israel, and his teachings comprise a major portion of the Palestinian Talmud. He is also quoted more than 4,000 times in the Babylonian Talmud. In addition to his knowledge of religious law (Halacha), he mastered mysticism (Talmud Hagiga 13a), the science of intercalating months (Palestinian Talmud, Rosh Hashana 2:6), medicine (Talmud Shabbat 109b; 110b), mathematics,[9] The pertinent references are: Talmud Eruvin 14a and 76a; Suca 7b; Menahot 97b 98a; Palestinian Talmud Kilaim 2:8 and 5:3; Midrash Kohelet Raba chapter 12, first section; etc. and other sciences [12, 10: 144-147].

2. The Biblical and Talmudic approximation of π

The Rabbinical approximation of π is discussed[10] Of course, the symbol π was not used in the early Rabbinical literature. The number π was usually referred to indirectly, or by the ratio of the circumference of a circle to its diameter, the number which when multiplied by the diameter produces the circumference, etc. in the Babylonian Talmud, Eruvin 14a. The Mishna there states the rule “Every [circle] whose circumference is three handbreadths, is one hand-breadth wide”[11] This rule also appears in the Talmud, Eruvin 76a and Suca 7b, etc. A variation of this rule appears in Mishna Ohalot X II 6. (hence the ratio of the circumference of a circle to its diameter is taken to be π0 = 3). The Gemara asks “Where is this learned from?” Rabbi Yohanan gives the Biblical authority the verse 1 Kings 7:23 “And he made a molten sea [tank], ten cubits from one brim to the other. It was round all about, and its height was five cubits. And a line of thirty cubits did circle it round about.” The Gemara argues “But it had a brim,” that is, the diameter perhaps was measured from outside, while the circumference was measured from inside, and therefore the given value does not represent π. Rabbi Papa suggests that the brim was very thin, therefore negligible. Again, the Gemara objects: “But there is still a slight [thickness],” so the value 3 given above would not describe the ratio of the circumference to the (whole) diameter. Therefore, the Gemara concludes, both the circumference and the diameter given in the verse refer to the inner side of the tank, as otherwise the Mishna would not have stated the rule as is.

This might seem very surprising [1], knowing that the ancient Babylonians and Egyptians used better approximations long before the verse 1 Kings 7:23 was written.[12] The dating of this verse is ambiguous. It was written after ca. 965 BCE (when Solomon became a king), but not much later than 561 BCE [12, 8: 766-777];[12, 10: 1030]. We see that the Gemara insists on learning the ratio π0 = 3 from the Bible, as an exact parameter in calculations for religious purposes. Moreover, Rabbi Yohanan does not answer, ‘This is a mathematical fact,’ nor does he say ‘One can check this via measuring,’ because it is known that the value is not mathematically correct.[13] In Mishnai Ha-Midot, the value ,3 1/7 is used for π. According to [6, 12], [12, 11: 1121-1124] and [26, 208-209], this text dates to the second century CE, and shows that the value 3 1/7 was known to the Jewish sages at that time. Gad B. Sarfatti in [24];[25] argues for a redating of Mishnat Ha-Midot to between 850 and 1200 CE, but see [14, 156];[2,3] for certain doubts concerning this re-dating. Hence, he answers that it is written in the Bible, telling us that we should use it for religious purposes, regardless of its being mathematically correct or not.

Another geometric rule given in the Talmud (Eruvin 56b, 76a; Suca 7b) is “How much is the square greater than the [inscribed] circle? A quarter,” that is, the circumference of a circle inscribed in a square is a quarter less than (or 3/4 of) the perimeter of the square. There is a corresponding areal rule (Eruvin 76b, Suca 8a), saying that this is the case with the ratio of the areas as well: “A circle in a square a quarter.” These rules are immediate consequences of the usual geometrical rules and the approximation π0 = 3.[14] Indeed, these rules are equivalent to the rules A = πr2 = x/4 × d2, P = πd = π/4 × 4d, where d2 is the area of the square, 4d is its perimeter, and π is taken to be 3. In [29];[30], we discuss a proof which derives the areal rule from the rule for the circumference using infinitesimals.

It is interesting to check whether more precise values were known to the ancient Hebrews. The answer to this may be found in the Hebrew Bible [21] ;[22], There is a Rabbinical tradition on the reading-versus-writing disparity in 1 Kings 7:23. According to Hebrew scriptural tradition, the word meaning “line” is written as ,קוה but read as קו . This is exactly the case with the values for π. Even though we see (via measuring or mathematical proof) a more precise value for π, call it πH, the Hebrew tradition tells us to use the value 3 (for religious purposes). In gematria,[15] Gematria (from the Greek ϒεωμετρία) is a mathematical method which uses letters to signify numbers (for example in Hebrew, א = 1, ב = 2 , etc.). Words have the numerical value which is the sum of the numerical values of their letters [1];[12, 7: 369]. this is expressed in the following equation of the ratios whence πH/3 = קוה/קו = 111/106, whence πH = 3 × 111/106 = 3 + 15/106 = 3.1415094 …, while π = 3.1415926… .[16] Unfortunately, there are not any known references to this exegesis in literature earlier than [21] (Medieval commentators used the values 3 1/7 or “a little less than 3 1/7” for π.) It is possible that Matityahu Hacohen Munk [21] was the first to note this fact. It is impossible to answer the question whether the above exegesis is the reason for the disparity or not (see also [1]), though there is some traditional evidence in favor of Munk’s explanation; see [8]. Here, we shall give an analysis suggesting that this value was indeed known to Rabbi Yohanan. It is interesting to mention, in this context, another ancient gematria: an inscription of Sargon II (727-707 BCE) states that the king built the wall of Khorsabad 16,283 cubits long to correspond with the numerical value of his name [12, 7: 369].

Why, then, not use a more precise value? Maimonides,[17] This is Rabbi Moshe (Moses) Ben Maimon, acronym Rambam (1135-1204 CE), whose Arabic name was Ibn al Maimūn. He was said to be The greatest Moses after the first Moses. in Perush Ha-Mishna (his commentary to the Mishna), Mishna Eruvin I 5, states the irrationality of π:

You need to know that the ratio of the circle’s diameter to its circumference is not known and it is never possible to express it precisely. This is not due to a lack in our knowledge, as the sect called Gahaliya [the ignorants] thinks; but it is in its nature that it is unknown, and there is no way [to know it], but it is known approximately. The geometers have already written essays about this, that is, to know the ratio of the diameter to the circumference approximately, and the proofs for this. This approximation which is accepted by the educated people is the ratio of one to three and one seventh. Every circle whose diameter is one hand-breadth, has in its circumference three and one seventh hand-breadths approximately. As it will never be perceived but approximately, they [the Hebrew sages] took the nearest integer and said that every circle whose circumference is three fists is one fist wide, and they contented themselves with this for their needs in the religious law [13];[20].

Maimonides’ statement is one of the earliest extant ones making that claim.[18] Various ancient Greek writers, including Hero, Eutocius, and Simplicius, understand the difficulty of finding an exact value for the ratio, and seem to realize the possibility of its being irrational [17], yet it appears that none of their extant statements are as strong as Maimonides [15]. See also [16, 363-364]. As for medieval mathematicians preceding Maimonides, we have the following: Yusuf al Mu’tam an (11th century CE), in the Istikmal (which was revised and taught by Maimonides) cites π in the chapter dealing with irrationality [9, 247]. However, he does not explicitly assert such suspicions. The only explicit statement concerning the irrationality of π in the earlier extant literature is to be found in al Biruni’s Masudic Canon (ca. 1030 CE) (Qanun al-Mascudi, Book III, Chapter 5): and the number of the circumference has also a ratio to the number of the diameter, although this (ratio) is irrational [4, 217];[10]. It is not known whether Maimonides knew the Masudic Canon [11].

Anyway, the irrationality of π was proved (by Lambert) only in the eighteenth century. It is therefore still a mystery what made Maimonides so sure about the irrationality of π.

Victor J, Katz [15] has noted that this is similar to Ptolemy’s claim (in Almagest I, 10) that one cannot trisect an angle using a straightedge and a compass: The chord corresponding to an arc which is one third of the previous one cannot be found by geometrical methods [27, 54].

Matityahu Hacohen Munk [21] ;[22] suggests a mystical explanation: some of the geometrical rules did not hold in King Solomon’s temple, according to Hebrew ancient traditions (see, for instance, Talmud Megilla 10b; Yoma 21a; Baba Batra 99a [7]; [8];[28]). In the temple, the ratio of the circumference of a circle to its diameter was exactly π0.[19] For geometric and physical models where circles may have this property, see [28]. In our reality this fails, but in order to join our reality with the “world of truth,”[20] For Isaac Newton, “The temple of Solomon was the most important embodiment of a future extra-mundane reality, a blueprint of heaven; to ascertain every last fact about it was one of the highest forms of knowledge, for here was the ultimate truth of God s kingdom expressed in physical terms” [18, 162] (quoted in [1];[3]). the temple’s values should be used in calculations for religious purposes.

Of course, applying the halachic π0 naively to our reality would yield circles which do not satisfy the halachic requirements. For example, in order for a circle (in our reality) to circumscribe a certain square, its circumference must be π times the diagonal of the square. Using π0 yields a circle too small.

Nevertheless, even in our reality, it is possible to “experience” π0 in a manner of speaking. This is accomplished if one computes the circumference not of the circle but rather of the regular hexagon inscribed in it. Then, the circle circumscribing this hexagon will satisfy the halachic requirements; it will circumscribe the square in the above example.

Rabbi Haim David Z. Margaliot [19] noted this possibility more than two decades before Munk.[21] He did not, however, suggest the idea of alternative geometry in the Temple. He suggests that the reason for this was that the circumference of the circle was measured from inside using a stick[22] It would have been difficult to measure from inside using a rope. of length equal to the radius of the needed circle. In his interpretation, one edge of the stick was placed at an arbitrary point A on the circle, and the other edge was used to find the point B on the circle. Then the edge was put on B in order to find C , etc. (see Fig. 1). If, after six iterations, the stick’s edge returned to the point A. then the “circumference” of the circle was six times the length of the stick or π0 times the diameter.[23] If there was an overlap, then the circle was considered to have a smaller circumference, and in the remaining case, it had a larger circumference.

Similarly, when the halachic requirement is on the area of the circle, the calculation involving π0 is applied to the inscribed regular dodecagon [19];[21];[22].[24] We have found no reasonable justification for this claim (apart from the fact th a t the dodecahedron satisfies the halachic formula for the area).

Rabbi Shimon Ben Tsemah (1361-1444) suggests another explanation in The Tashbets (part I, responsa 165): in fact, more precise values for π were known to the Talmudic Rabbis, but in order for their students to understand, they used the less precise value “One should always teach his student in the easiest way” (Talmud Pesahim 3b; 63b). However, de facto they used more precise values. In order to understand this, we have to introduce the relevant parts from the discussion held in Talmud Suca 7b 8b.[25] For a comprehensive discussion, see [7];[8]. Here, we follow the presentation of [5].

Relying on Rav’s[26] Rav (third century CE) was a leading Babylonian Amora and founder of the academy at Sura. His name was Abba ben Aivu. He is generally known as Rav since he was the teacher (Rabbi) of the entire diaspora (Talmud Betsa 9a, and Rashi thereto) [12, 13: 1576]. rule that “A [square] booth (or tabernacle) less than 4 by 4 cubits is unfit,” Rabbi Yohanan said: “A booth built in the form of a kiln (that is, circular) whose circumference is long enough to seat 24 persons is fit for use; if not, it is unfit.”[27] Note that the booth is not intended for the use of the twenty four mentioned persons. The statement only gives a way to estimate the circumference of the booth. Knowing that one person occupies one cubit by one cubit, the Gemara finds the minimal circumference of a circular booth sufficiently large to contain a square of side 4 cubits.

The diameter of the booth is the diagonal of the square, which is according to the rule “Each hand-breadth in a square is 1 2/5 hand-breadths in its diagonal”[28] Hence √2 is taken to be 1 2/5. This value is presented in Talmud Eruvin 76a; Suca 8a, etc. 4 × 1 2/5 = 5 3/5. Hence, the circumference is 5 3/5 π0 = 16 4/5. Rabbi Assi provides an explanation of Rabbi Yohanan’s statement: the twenty four persons should sit outside the booth (see note 25), as follows (Fig. 3),

where each section corresponds to the space occupied by one person. The circumference of the circle circumscribing the persons is, according to Rabbi Yohanan’s statement, 24 cubits; therefore its diameter is 24/π0 = 8 cubits. As the diameter of the booth is 2 cubits (one from each side) less than the diameter of the outer circle, we conclude that the diameter of the booth is 6 cubits.[29] Here we must use the fact that the space occupied by a person is flexible and may be less than one square cubit. This may be the reason why Rabbi Yohanan uses the term persons instead of cubits. Rabbi Yohanan thus gives us an ingeniously practical method, understandable even to the mathematically illiterate person, to check that the booth has a circumference of 18 cubits.[30] We shall soon see that the situation is much more complicated, and Rabbi Yohanan’s method elegantly bypasses these complications. As 18 cubits is more than the minimum (16 4/5 cubits) required, it seems that Rabbi Yohanan did not mind being somewhat inexact.

However, the following problem now arises:[31] Other problems, which are beyond the scope of this paper, also arise (see [2]), However, the solution we present here is ju st as good for the problems which are not discussed here. Rabbi Yohanan’s words “if not, it is unfit” suggest that he was very precise in his statement. Moreover, Rabbi Yohanan said (Talmud Shabbat 145b)[32] This concerns the verse (Proverbs 7:4) Tell the wisdom: Thou art my sister.” “If it is as clear as day, say it; if not, do not say it.” If indeed Rabbi Yohanan used the inexact values, he could have said that twenty three persons are sufficient. This would give (23/π0 – 2)π0 = 17 cubits for the circumference of the booth, which is much closer to 16 4/5 and yet more than the minimum requirement.

The solution to this problem is to be found in Rabbi Shimon ben Tsemah’s explanation, which is as follows. Rabbi Yohanan’s statement is quite precise, if we assume that he used more precise values for π and √2.[33] The inaccuracy of the value 1 2/5 is proved in the Tosafot commentary (see note 4) on Talmud Suca 8a. The proof is as follows: take a square of side 10 cubits, and join the central points of its sides to form a square of area half of the original’s or 50 squared cubits. According to the above rule, the side of the new square is 5 × 1 2/5 = 7 cubits, hence its area is 49 squared cubits, a contradiction. This proves that 5 √2 > 7 or √2 >7/5 = 1 2/5. For this, he takes 3 1/7 for π and d “slightly greater than 1 2/5” for √2. The minimum circumference is (see Fig. 2) 4 × d × 3 1/7 which is a little more than 17 3/5. The circumference of the booth is (see Fig. 3) (24/ 3 1/7 -2) 3 1/7 = 17 5/7, which is more than the minimum 17 3/5 and the difference is not more than 4/35 cubits.

Of course, we do not intend to claim that Rabbi Yohanan knew the exact numerical values for π and √2. Yet, we suggest that Rabbi Yohanan may have known the value πH given in the above exegesis.[34] Note tha 3 15/106, which is a lower bound, is a very interesting value, and may have been worked out also by Archimedes, although the evidence is ambiguous; Ptolemy’s value is 3 17/120, which is a corresponding upper bound. It seems that these, or better values, were already known in the second century BCE, by Apollonius [17]. See also [16, 157-158]. Note that πH is the third convergent in the continued fraction of π [1, 96]. We begin by reversing the computation of the circumference circumscribing the square.

Suppose √2R is an approximation of √2 such that (24/πH -2) πH = 4√2RπH. Then √2R = 1 91/222 = 1.4099099099. It is reasonable to assume that Rabbi Yohanan used √2Y := 1 2/5 + 1/100 = 1.41 for √2.[35] The fraction 1/100 occurs many times in the Rabbinical literature, mostly as is, and sometimes as 1/10 of 1/10. See Mishna Demai V 1; Maaser Sheni IV 8; Baba Kama V II 5. An even more precise approximation for √2 is given indirectly in Mishna Eruvin V 3. It is said there that twice the side of a square whose area is 5000 square cubits is equal to 141 1/3 cubits, i.e., 2√5000 = 141 1/3, whence √2 = 1 31/75 = 1.41 + 1/300 = 1.41333 Whence we get an inaccuracy of 4√2YπH – (24/πH -2)πH = 3/2650 = 0.001132… cubits.

Surprisingly, good approximations can be reconstructed without the assumption that Rabbi Yohanan knew the value πH: for example, the global minimum of the weighted error function

√(π-x/π)2 + (√2-y/√2)2

under the condition (24/x – 2)x = 4yx is attained at

(x0, y0) = (3.136966…,1.412675…).

This gives independent mathematical evidence that more exact values were indeed used by Rabbi Yohanan.

* * *

In summary, the following are the major approaches to the understanding of the Biblical and Talmudic value for π:

1. The rational religious approach of Maimonides holds that, since we cannot know the exact values, the Bible tells us that we do not have to worry about this and that it suffices to use the value 3.[36] In his Halachic sentences, Maimonides elegantly bypasses the irrationality problem by saying that the circle should be large enough to contain the square in question.

2 . The mystical approach of Munk contends that 3 was indeed the ratio of the circumference to the diameter in King Solomon’s temple: This value is used in order to bridge the gap between our world and the “world of truth.” For the sake of consistency, the halachic conditions are applied to the suitable regular polygons.

3. The practical approach of Rabbi Shimon ben Tsemah asserts that the rough approximations are used when teaching the students, but, when it comes to practice, the calculations are to be done by the experts.

3. Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the following people for their help in various stages of this paper: Shlomo Edward Belaga of Louis Pasteur University; Wilbur Richard Knorr[37] deceased. of Stanford University; William C. Waterhouse of Pennsylvania State University; Hussam Arisha Hag Ihia, Eliyahu Beller, and Jonathan Staviall of Bar Ilan University. We owe special thanks to Victor J. Katz from the University of the District of Columbia for his helpful remarks. Finally, we would like to thank the referees and editors for their part in bringing the paper to its current form.

References

1. Edward Shlomo G. Belaga, On the Rabbinical Exegesis of an Enhanced Bibilical Value of π, in: Proceedings of the XVII tk Canadian Congress of History and Philosophy of Mathematics, Kingston, Ontario: Queen’s University, 1991, pp. 93-101.

2. Haim Brener, A Booth Built in the Form of a Kiln, Maaliyot, 4 (1983), 51-54. [in Hebrew]

3. John Brooke, The God of Isaac Newton, in: Let Newton Be/, ed. John Fauvel et. al,, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988, 166-183

4. Pavel G. Bulgakova and Boris A. Rozenfeld, Abu Raikhan Beruni (973-1048), Izbrannye proizvedeniya V. Part 1. Kanon Mas uda (Knigi I- V) . . . perevod i primechaniya, Tashkent: Fan, 1973. [in Russian]

5. William Moses Feldman, Rabbinical Mathematics and Astronomy, New York: Hermon Press, 1931.

6. Solomon Gandz, The Mishnat ha Middot, Quellen und Studien zur Geschichte der Mathematik, Astronomic und Physik A2 (1932), Berlin: Springer Verlag.

7. David Garber and Boaz Tsaban, A Circular Booth, Magal, 10 (1994), 117-134. [in Hebrew]

8. ______ , A Circular Booth II, Magal, 11 (1995), 127-134. [in Hebrew]

9. Jan P. Hogendijk, The Geometrical Parts of the Istikmal of Yusuf al Mu’tam an Ibn Hud, Archives Internationales D Histoire des Sciences 41 (1991), 207-281.

10. ______ , The Scientific Work of Rosenfeld, in: Festschrift for Rosenfeld, to appear.

11. ______ , private communication, September 11, 1996.

12. Encyclopedia Judaica, Jerusalem: Keter Publishing House, 1972.

13. Rabbi Yosef David Kappah, Mishna with Maimonides Commentary, Mo ed section, Jerusalem: Mosad Harav Kook 1963, 63-64. [in Hebrew]

14. Victor J. Katz, A History of Mathematics: An Introduction, New York: HarperCollins College Publishers, 1993.

15. ______ , private communication, January 22, 1995.

16. Wilbur Richard Knorr, The Ancient Tradition of Geometric Problems, New York: Dover Publications, 1993.

17. ______ , private communication, June 11, 1993.

18. Frank Edward Manuel, Isaac Newion, Historian, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1963.

19. Rabbi Haim David Zilber Margaliot, Dover Yesharim (Moadim section), 1938, reprinted,: Giv’atayim: Kulmus 1959, 102-105. [in Hebrew]

20. Mishna, Mo’ed section, Jerusalem: Me’orot 1973, 106-107. [in Hebrew]

21. Matityahu Hacohen Munk, Three Geometric Problems in the Bible and the Talmud, Sinai 51 (1962), 218-227. [in Hebrew]

22. ______ , The Halachic Way in Solving Special Geometric Problems, Hadarom 27 (1968), 115-133. [in Hebrew]

23. Erwin Neuenschwander, Reflections on the Sources of Arabic Geometry, Sudhoffs Archiv, 72 (1988), 160-169.

24. Gad B. Sarfatti, The Mathematical Terminology of the Mishnat Ha Midot, Leshonenu 23 (1959), 156-171. [in Hebrew]

25. ______ , The Mathematical Terminology of the Mishnat Ha Midot (part II), Leshonenu 24 (1960), 73-94. [in Hebrew]

26. George Sarton, Introduction to the History of Science, 2, part I, Washington Baltimore: Carnegie Institution of Washington, 1931.

27. Gerald Toomer, Ptolemy’s Almagest, New York: Springer Verlag, 1984.

28. Boaz Tsaban, On the Ratio of the Circumference of a Circle to its Diameter, Sinai 117 (1996), 186-191. [in Hebrew]

29. Boaz Tsaban and David Garber, Every [Circle] whose Circumference, Higayon 3 (1995), 103-131. [in Hebrew]

30. Boaz Tsaban, David Garber, and Victor J. Katz, The Proof of Rabbi Abraham Bar Iliya Hanasi, in preparation.

Source(s)

“It is interesting to check whether more precise values were known to the ancient Hebrews. The answer to this may be found in the Hebrew Bible [21] ;[22], There is a Rabbinical tradition on the reading-versus-writing disparity in I Kings 7:23. According to Hebrew scriptural tradition, the word meaning ‘line’ is written as קוה, but read as קו.” (from “On the Rabbinical Approximation of Pi” by Boaz Tsaban and David Gardner)

Notes

| 1 | Matityahu Hacohen Munk, “Three Geometric Problems in the Bible and the Talmud,” Sinai 51 (1962), 218-227. [in Hebrew] |

|---|---|

| 2 | ibid, “The Halachic Way in Solving Special Geometric Problems,” Hadarom 27 (1968), 115133. [in Hebrew] |

| 3 | Thus, e.g., Mishna Ohalot X II 6 means: Mishna, tractate Ohalot, chapter X II, sixth paragraph (tractate Ohalot is in section Teharot, bu t the section is usually omitted). |

| 4 | Unless otherwise indicated, Talmud always refers to the Babylonian Talmud. |

| 5 | Rashi is the acronym of Rabbi Shlomo Itshaqi of Troyes (1040-1105 CE). |

| 6 | The word Tosafot means addendas. This commentary was written mainly by Rashi’s sons-in-law and grandsons during the 12th and 13th centuries CE. |

| 7 | Thus, e.g., Talmud Suca 8a means: (Babylonian) Talmud, tractate Suca, folio number 8, first page. The Palestinian Talmud, on the other hand, is referred to by the tractate, the chapter, and the paragraph number. Palestinian Talmud, Rosh Hashana 2:6 thus refers to the sixth paragraph of the second chapter in tractate Rosh Hashana of the Palestinian Talmud. |

| 8 | A good reference on the Talmud is [12, 15: 750-779]. |

| 9 | The pertinent references are: Talmud Eruvin 14a and 76a; Suca 7b; Menahot 97b 98a; Palestinian Talmud Kilaim 2:8 and 5:3; Midrash Kohelet Raba chapter 12, first section; etc. |

| 10 | Of course, the symbol π was not used in the early Rabbinical literature. The number π was usually referred to indirectly, or by the ratio of the circumference of a circle to its diameter, the number which when multiplied by the diameter produces the circumference, etc. |

| 11 | This rule also appears in the Talmud, Eruvin 76a and Suca 7b, etc. A variation of this rule appears in Mishna Ohalot X II 6. |

| 12 | The dating of this verse is ambiguous. It was written after ca. 965 BCE (when Solomon became a king), but not much later than 561 BCE [12, 8: 766-777];[12, 10: 1030]. |

| 13 | In Mishnai Ha-Midot, the value ,3 1/7 is used for π. According to [6, 12], [12, 11: 1121-1124] and [26, 208-209], this text dates to the second century CE, and shows that the value 3 1/7 was known to the Jewish sages at that time. Gad B. Sarfatti in [24];[25] argues for a redating of Mishnat Ha-Midot to between 850 and 1200 CE, but see [14, 156];[2,3] for certain doubts concerning this re-dating. |

| 14 | Indeed, these rules are equivalent to the rules A = πr2 = x/4 × d2, P = πd = π/4 × 4d, where d2 is the area of the square, 4d is its perimeter, and π is taken to be 3. |

| 15 | Gematria (from the Greek ϒεωμετρία) is a mathematical method which uses letters to signify numbers (for example in Hebrew, א = 1, ב = 2 , etc.). Words have the numerical value which is the sum of the numerical values of their letters [1];[12, 7: 369]. |

| 16 | Unfortunately, there are not any known references to this exegesis in literature earlier than [21] (Medieval commentators used the values 3 1/7 or “a little less than 3 1/7” for π.) It is possible that Matityahu Hacohen Munk [21] was the first to note this fact. It is impossible to answer the question whether the above exegesis is the reason for the disparity or not (see also [1]), though there is some traditional evidence in favor of Munk’s explanation; see [8]. Here, we shall give an analysis suggesting that this value was indeed known to Rabbi Yohanan. It is interesting to mention, in this context, another ancient gematria: an inscription of Sargon II (727-707 BCE) states that the king built the wall of Khorsabad 16,283 cubits long to correspond with the numerical value of his name [12, 7: 369]. |

| 17 | This is Rabbi Moshe (Moses) Ben Maimon, acronym Rambam (1135-1204 CE), whose Arabic name was Ibn al Maimūn. He was said to be The greatest Moses after the first Moses. |

| 18 | Various ancient Greek writers, including Hero, Eutocius, and Simplicius, understand the difficulty of finding an exact value for the ratio, and seem to realize the possibility of its being irrational [17], yet it appears that none of their extant statements are as strong as Maimonides [15]. See also [16, 363-364]. As for medieval mathematicians preceding Maimonides, we have the following: Yusuf al Mu’tam an (11th century CE), in the Istikmal (which was revised and taught by Maimonides) cites π in the chapter dealing with irrationality [9, 247]. However, he does not explicitly assert such suspicions. The only explicit statement concerning the irrationality of π in the earlier extant literature is to be found in al Biruni’s Masudic Canon (ca. 1030 CE) (Qanun al-Mascudi, Book III, Chapter 5): and the number of the circumference has also a ratio to the number of the diameter, although this (ratio) is irrational [4, 217];[10]. It is not known whether Maimonides knew the Masudic Canon [11]. Anyway, the irrationality of π was proved (by Lambert) only in the eighteenth century. It is therefore still a mystery what made Maimonides so sure about the irrationality of π. Victor J, Katz [15] has noted that this is similar to Ptolemy’s claim (in Almagest I, 10) that one cannot trisect an angle using a straightedge and a compass: The chord corresponding to an arc which is one third of the previous one cannot be found by geometrical methods [27, 54]. |

| 19 | For geometric and physical models where circles may have this property, see [28]. |

| 20 | For Isaac Newton, “The temple of Solomon was the most important embodiment of a future extra-mundane reality, a blueprint of heaven; to ascertain every last fact about it was one of the highest forms of knowledge, for here was the ultimate truth of God s kingdom expressed in physical terms” [18, 162] (quoted in [1];[3]). |

| 21 | He did not, however, suggest the idea of alternative geometry in the Temple. |

| 22 | It would have been difficult to measure from inside using a rope. |

| 23 | If there was an overlap, then the circle was considered to have a smaller circumference, and in the remaining case, it had a larger circumference. |

| 24 | We have found no reasonable justification for this claim (apart from the fact th a t the dodecahedron satisfies the halachic formula for the area). |

| 25 | For a comprehensive discussion, see [7];[8]. Here, we follow the presentation of [5]. |

| 26 | Rav (third century CE) was a leading Babylonian Amora and founder of the academy at Sura. His name was Abba ben Aivu. He is generally known as Rav since he was the teacher (Rabbi) of the entire diaspora (Talmud Betsa 9a, and Rashi thereto) [12, 13: 1576]. |

| 27 | Note that the booth is not intended for the use of the twenty four mentioned persons. The statement only gives a way to estimate the circumference of the booth. |

| 28 | Hence √2 is taken to be 1 2/5. This value is presented in Talmud Eruvin 76a; Suca 8a, etc. |

| 29 | Here we must use the fact that the space occupied by a person is flexible and may be less than one square cubit. This may be the reason why Rabbi Yohanan uses the term persons instead of cubits. |

| 30 | We shall soon see that the situation is much more complicated, and Rabbi Yohanan’s method elegantly bypasses these complications. |

| 31 | Other problems, which are beyond the scope of this paper, also arise (see [2]), However, the solution we present here is ju st as good for the problems which are not discussed here. |

| 32 | This concerns the verse (Proverbs 7:4) Tell the wisdom: Thou art my sister.” |

| 33 | The inaccuracy of the value 1 2/5 is proved in the Tosafot commentary (see note 4) on Talmud Suca 8a. The proof is as follows: take a square of side 10 cubits, and join the central points of its sides to form a square of area half of the original’s or 50 squared cubits. According to the above rule, the side of the new square is 5 × 1 2/5 = 7 cubits, hence its area is 49 squared cubits, a contradiction. This proves that 5 √2 > 7 or √2 >7/5 = 1 2/5. |

| 34 | Note tha 3 15/106, which is a lower bound, is a very interesting value, and may have been worked out also by Archimedes, although the evidence is ambiguous; Ptolemy’s value is 3 17/120, which is a corresponding upper bound. It seems that these, or better values, were already known in the second century BCE, by Apollonius [17]. See also [16, 157-158]. Note that πH is the third convergent in the continued fraction of π [1, 96]. |

| 35 | The fraction 1/100 occurs many times in the Rabbinical literature, mostly as is, and sometimes as 1/10 of 1/10. See Mishna Demai V 1; Maaser Sheni IV 8; Baba Kama V II 5. An even more precise approximation for √2 is given indirectly in Mishna Eruvin V 3. It is said there that twice the side of a square whose area is 5000 square cubits is equal to 141 1/3 cubits, i.e., 2√5000 = 141 1/3, whence √2 = 1 31/75 = 1.41 + 1/300 = 1.41333 |

| 36 | In his Halachic sentences, Maimonides elegantly bypasses the irrationality problem by saying that the circle should be large enough to contain the square in question. |

| 37 | deceased. |

“יוֺם פּײַ | On the Rabbinical Approximation of π, by Boaz Tsaban and David Garber (1998)” is shared through the Open Siddur Project with a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International copyleft license.

Comments, Corrections, and Queries