In his introduction to a facsimile edition of Perek Shira,[1] Facsimile van Oriental Ms. 12.983 v.d. British Library. Genummerd exemplaar 253 van de 550 Dr. Malachi Beit-Arie writes the following:

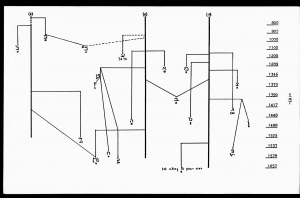

[Perek Shira] has been preserved in more than 100 manuscripts, 20 of them copied in the Middle Ages, including geniza fragments, the earliest dating from about the tenth century. The versions differ considerably in content and arrangement, and classification of the manuscripts reveals the existence of three distinct traditions: Oriental-Italian, Sephardi and Ashkenazi. The first printed edition, with a commentary by Moses b. Joseph de Trani (printed as an appendix to his Beit Elohim; Venice, 1576), was followed by some 100 corrupt editions, generally accompanied by commentaries, translations into Yiddish, Ladino and German, and literary paraphrases to this day. Perek Shira is first mentioned in a polemical work of Salmon b. Jerohim, a Jerusalem Karaite of the first half of the tenth century. References to it can be found in European sources at the end of the 12th century and from the 13th century onward various interpretations, mainly kabbalistic, are known. It would seem that from the outset Perek Shira was intended as a liturgical text, as also seems apparent from the pseudepigraphic mystical additions. In the early Ashkenazi manuscripts it was included in maḥzorim and collections of special prayers in close proximity to prayers issuing from circles of Ḥasidei Ashkenaz. The spread of the later custom of reciting Perek Shira as a prayer and its inclusion in printed prayer books was mainly due to the influence of the Safed kabbalists.

Talmudic and midrashic sources contain hymns of the creation usually based on homiletic expansions of metaphorical descriptions and personifications of the created world in the Bible. The explicitly homiletic background of some of the hymns in Perek Shira indicates a possible connection between the other hymns and Tannaitic and Amoraic homiletics, and suggests a hymnal index to well-known, but mostly unpreserved, homiletics. The origin of this work, the period of its composition and its significance may be deduced from literary parallels. A Tannaitic source in the tractate Ḥagiga of the Jerusalem (Ḥag. 2:1,77a—b) and Babylonian Talmud (Ḥag. 14b), in hymns of nature associated with apocalyptic visions and with the teaching of ma’aseh merkaba serves as a key to Perek Shira’s close spiritual relationship with this literature. Parallels to it can be found in apocalyptic literature, in mystic layers in Talmudic literature, in Jewish mystical prayers surviving in fourth-century Greek Christian composition, in Heikhalot literature, and in Merkaba mysticism. The affinity of Perek Shira with Heikhalot literature, which abounds in hymns, can be noted in the explicitly mystic introduction to the seven crowings of the cock — the only non-hymnal text in the collection — and the striking resemblance between the language of the additions and that of Shi’ur Koma and other examples of this literature. In Seder Rabba de-Bereshit, a Heikhalot tract, in conjunction with the description of ma’aseh bereshit, there is a clear parallel to Perek Shira’s praise of creation and to the structure of its hymns. The concept reflected in this source is based on a belief in the existence of angelic archetypes of created beings who mediate between God and his creation, and express their role through singing hymns. As the first interpretations of Perek Shira also bear witness to its mystic character and angelologic significance, it would appear to be a mystical chapter of Heikhalot literature, dating from late Tannaitic — early Amoraic period, or early Middle Ages.

Some parallels to Perek Shira exist outside Hebrew literature: the Testament of Adam (preserved in Syriac, Greek, and in later translations), which contains horaries of praise by the whole of creation framed in an apocalyptic angelologic vision similar to that in Seder Rabba de-Bereshit and may have originated from Jewish Hellenistic circles; the Greek Physiologus of the second century, which reveals structural and formal parallels to Perek Shira; and Islamic oral traditions (Hadith) on the praise of created beings.

Notes

| 1 | Facsimile van Oriental Ms. 12.983 v.d. British Library. Genummerd exemplaar 253 van de 550 |

|---|

“📖 פֶּרֶק שִׁירָה | Pereq Shirah, critical text by Dr. Malachi Beit-Arié (1967)” is shared through the Open Siddur Project with a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International copyleft license.

Leave a Reply