| Source (Hebrew) | Translation by I.M. Lask (English) | Translation by A.I. Cohon (English) |

|---|---|---|

הַחַמָּה מֵרֹאשׁ הָאִילָנוֹת נִסְתַּלְּקָה. בֹּֽאוּ וְנֵצֵא לִקְרַאת שַׁבָּת הַמַּלְכָּה. הִנֵּה הִיא יוֹרֶֽדֶת הַקְדוֹשָׁה הַבְּרוּכָה. וְעִמָּהּ מַלְאָכִים צְבָא שָׁלוֹם וּמְנוּחָה: בֹּֽאִי בֹּֽאִי הַמַּלְכָּה. בֹּֽאִי בֹּֽאִי הַכַּלָּה. שָׁלוֹם עֲלֵיכֶם מַלְאֲכֵי הַשָּׁלוֹם: |

The sun o’er the treetops no longer is seen; Come, let us go forth and greet Sabbath the Queen. Behold her descending, the holy and blest, And with her the angels of peace and of rest. Welcome, welcome, queen and bride, Welcome, welcome, queen and bride. Peace be unto you, angels of peace. |

The sun on the tree-tops no longer is seen, Come, gather to welcome the Sabbath, our Queen. Behold her descending, the holy, the blest, With angels—a cohort of peace and of rest. Draw nigh, O Queen, and here abide; Draw nigh, draw nigh, O Sabbath bride. Peace also to you, Ye angels of peace! |

קִבַּֽלְנוּ פְנֵי שַׁבָּת בִרְנָנָה וּתְפִלָּה. הַבַּֽיְתָה נָשׁוּבָה בְּלֵב מָלֵא גִילָה. שָׁם עָרוּךְ הַשֻּׁלְחָן הַנֵרוֹת יָאִֽירוּ. כָּל־פִּנוֹת הַבַּֽיִת יִזְרָֽחוּ יַזְהִירוּ. שַׁבַּת שָׁלוֹם וּבְרָכָה. שַׁבַּת שָׁלוֹם וּמְנוּחָה. בֹּאֲכֶם לְשָׁלוֹם מַלְאֲכֵי הַשָּׁלוֹם: |

The Sabbath is greeted with song and with praise, We go slowly homewards, our hearts full of grace. The table is spread there, the candles give light, Every nook in the house is shining and bright. Sabbath is peace and rest. Sabbath is peaceful and blest. Enter in peace, ye angels of peace. |

We’ve welcomed the Sabbath with song and with prayer; And home we return, our heart’s gladness to share. The table is set and the candles are lit, The tiniest corner for Sabbath made fit. O day of blessing, day of rest! Sweet day of peace be ever blest! Bring ye also peace, Ye angels of peace! |

שְׁבִי זַכָּה עִמָּֽנוּ וּבְזִיוֵךְ נָא אֽוֹרִי לַיְלָה וָיוֹם אַחַר תַּעֲבֹֽרִי. וַאֲנַחְנוּ נְכַבְּדֵךְ בְּבִגְדֵי חֲמוּדוֹת. בִּזְמִירוֹת וּתְפִלּוֹת וּבְשָׁלֹשׁ סְעֻדוֹת: וּבִמְנוּחָה שְׁלֵמָה. וּבִמְנוּחָה נָעֵֽמָה. בָּרְכֽוּנוּ לְשָׁלוֹם מַלְאֲכֵי הַשָּׁלוֹם: |

O pure one, be with us and light with thy ray The night and the day; then pass on thy way. And we do thee honor with garments most fine, With songs and with prayer and with three feasts with wine, And sweetness of peace, And perfect peace. Bless us with peace, ye angels of peace. | |

הַחַמָּה מֵרֹאשׁ הָאִילָנוֹת נִסְתַּלְּקָה. בֹּֽאוּ וּנְלַוֶּה אֶת־שַׁבָּת הַמַּלְכָּה. צֵאתֵךְ לְשָׁלוֹם הַקְּדוֹשָׁה הַזַּכָּה. דְעִי שֵֽׁשֶׁת יָמִים אֶל־שׁוּבֵךְ נְחַכֶּה: כֵּן לַשַּׁבָּת הַבָּאָה. כֵּן לַשַּׁבָּת הַבָּאָה. צֵאתְכֶם לְשָׁלוֹם מַלְאֲכֵי הַשָׁלוֹם: |

The sun in the treetops no longer is seen, Come forth and let us speed Sabbath the Queen. Go forth in peace, holy and pure, Know that for six days we await you, secure Until the coming Sabbath, Until the coming Sabbath, Go forth in peace, ye angels of peace. |

This translation of Ḥayyim Naḥman Bialik’s “Shabbat ha-Malkah” by Israel Meir Lask can be found on pages 280-281 in the Sabbath Prayer Book (Jewish Reconstructionist Foundation, 1945) where it appears as “Greeting to Queen Sabbath.” The poem is based on the shabbat song, “Shalom Alekhem,” and first published in the poetry collection, Hazamir, in 1903. I have made a faithful transcription of the Hebrew and its English translation as it appears in the Sabbath Prayer Book.

The first stanza of Lask’s translation was adapted from an earlier translation made by Angie Irma Cohon and published in 1920 in Song and Praise for Sabbath Eve (1920), p. 87. Cohon’s translation of Bialik’s second stanza of “Shabbat ha-Malkah” does not appear to have been adapted by Lask. (Thank you to Dr. Noam Sienna for informing us of Angie Irma Cohon’s translation.) –Aharon N. Varady

Source(s)

“שַׁבָּת הַמַּלְכָּה | The Shabbat Queen, by Ḥayyim Naḥman Bialik (1903)” is shared through the Open Siddur Project with a Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication 1.0 Universal license.

(RNS) — For a patriarchal religion, you must admit Judaism does not lack for feminine images, typologies and role models.

Even when they seem to be redundant and/or contradictory.

This occurred to me several weeks ago, during Friday evening services. As we were entering Shabbat, we sang two traditional hymns. Both of them featured imaginary women in starring roles.

First, we sang the classic Shabbat evening hymn, “Lecha Dodi.” “Beloved, come, and let us greet the Shabbat bride.” These were the words, penned by the Safed mystic, Shlomo Alkabetz, who actually embedded his own name as an acrostic into the verses of the song.

Here, Shabbat is a bride. At the end of the song, just as you would do at a traditional wedding, the congregation rises, turns towards the sanctuary entrance, and, with a bow, welcomes the invisible bride.

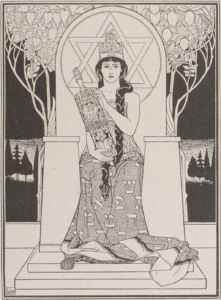

But, wait. Right after that, we sang an almost equally famous hymn, “Ha-chamah mei-rosh.” In the words of the Hebrew literary giant, Bialik: “The sun on the tree tops no longer is seen. Come let us welcome the Sabbath, our Queen.”

Shabbat is a queen because you must show deference to her and obey her.

First, it was Shabbat as Bride. Now, it’s Shabbat as Queen. Which is it?

The answer: both. Both Bride and Queen, manifestations of the Divine Presence. Both of them aspects of God. Both of them mythical memories of ancient goddesses.

Shabbat is both a bride and a queen, because the way you relate to a bride is very different from the way you relate to a queen.

You go to a wedding, and you are able to talk to the bride. You might even hug her, kiss her and dance with her.

That’s the bride. But, the Queen is different.

Try as I might, I cannot give up my thing about the royals. I watched the Netflix series, “The Crown” all the way through — twice.

But, one of my favorite cinematic excursions into royalty is “The Queen.” It is about the annus horribillus, the horrible year in which Princess Diana died in that infamous automobile accident in Paris.

The English people are grieving terribly. In their grief, they no longer want the traditional stiff upper lip of the monarchy. There are many who are not even so sure they want the monarchy. They want the Queen to be with them in their grief — which literally means they want the Queen to grieve with them over this terrible loss. They want her to express ordinary human feelings — even if those feelings are laced with appropriate ambivalence about the broken relationship that preceded Diana’s unhappy and untimely death.

They not only want the Queen. They want their Mother.

My favorite scene is the one in which Prime Minister Tony Blair must prepare himself for his first meeting with Queen Elizabeth. He must review the entire protocol — where to stand, how to stand, how to bow, what to call her (at first meeting), what to call her subsequently.

In “The King’s Speech,” speech therapist Lionel Logue takes personal liberties with the soon-to-be King George VI, whom he calls by his nickname “Bertie” — a name reserved only for Bertie’s family members. Logue tells Bertie he could very well be a good king — to which the royal responds, “That’s very close to treason!” Mrs. Logue gets a quick tutorial by Queen Mary on how to address a queen: You start with “your majesty,” and then it’s ma’am, which really is supposed to come out as “mum.”

The Bride? No rules. The Queen? Rules.

So, that’s Judaism. Bride and Queen.

The Bride nature of Shabbat is about delight. “I enjoy Shabbat.”

The Queen nature of Shabbat is about rules. “I obey the laws of Shabbat.”

It turns out you need both — in whatever mixture you choose.

So, let’s talk about monarchy.

America rejected a king in 1776. We find the idea of kings and queens to be quaint but irrelevant, perhaps even dangerous. Most kings and queens in the world today have only symbolic power.

So, why do we love the royals? Because symbolic power is real power. Because it symbolizes.

Because it turns out we have not entirely cast off our desire for a Queen. Perhaps the roots are ancient and mythical, but they are there.

There is something within us that still wants, and needs, a Queen. (Even more, I daresay, than we want and need a King).

As the world says farewell to Queen Elizabeth II, the longest reigning monarch in British history, we remember a woman who served, in many ways, as a maternal and grandmotherly pre