This work is in the Public Domain due to the lack of a copyright renewal by the copyright holder listed in the copyright notice (a condition required for works published in the United States between January 1st 1924 and January 1st 1964).

This work was scanned by Aharon Varady for the Open Siddur Project from a volume held in the collection of the Varady family, Cincinnati, Ohio. (Thank you!) This work is cross-posted to the Internet Archive, as a repository for our transcription efforts.

Scanning this work (making digital images of each page) is the first step in a more comprehensive project of transcribing each prayer and associating it with its translation. You are invited to participate in this collaborative transcription effort!

INTRODUCTION

The High Holyday prayers share the general characteristic, of all Jewish prayer — they are outpourings of the spirit, stirred by the awareness of God. They are expressions of gratitude for God’s countless blessings or entreaties for help in meeting the commitments of living. But the High Holyday prayers have characteristics of their own, born of the meanings to which Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur are dedicated.

Both Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur deal with man on the plane of universality. It is not so much as the citizen of a community, but as a child of God that man faces his Creator on these days.

Man is endowed with a twofold nature. He is a little lower than the angels, a being upon whom is stamped the divine imago, a being who surges restlessly toward the heights. But he is also a creature of earth, torn by baser hungers. He knows the will to possess, to dominate, to seek ease and to gratify a variety of bodily pleasures at the expense of his higher good.

The days of Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur summon man to the vision that his real seif is the divine image within him, that the meaning of his life be measured in the victory he has achieved in disciplining his baser self and bending it to serve his higher purposes. These days summon him to continue his quest toward the highest, and to that end to renounce his sins, his deficiencies. It is because every man can be better than he is, that every man needs to renounce deficiency, to overcome sin.

Man’s sin is his clinging to the lower rather than the higher self. His sin may express itself in deeds done or deeds not done. But every deficiency, every sin has also a relationship to his Creator. It is a withdrawal from God, from the God whose image he bears. On the other hand, every step forward in his quest for perfection is a return to God. The Hebrew term for this return is teshuvah, and teshuvah is the continued call of the High Holyday season.

The need for teshuvah is grounded in one sense on the claim which God has upon man. God is the Father, the Provider, the gracious Giver, of all we have and all we prize. He yearns for our love not because our love adds anything to His perfection, but because our love for Him is an indication that we have understood our true relationship to Him.

But the need for teshuvah is also grounded on the consequences which derive from the alienation of man from God. Man is free, if he will, to turn his back upon his Creator, but he pays a price for this. For our lives are constantly under God’s judgment. Life without God is a life beset by the misery of loneliness and frustration. Sin is a kind of sickness, a sickness of the spirit, and the only therapy open to us is to renounce sin, to return to God. Teshuvah is the road to the healing of the spirit.

The High Holyday prayers are inspired by these grand conceptions. But our understanding of these prayers is often obscured by the idiom in which they are expressed. The Hebrew language abounds in metaphors and figurative expressions. The language of prayer, especially, because it is a language of poetry, tends to draw on various figures of speech, on literary and historic allusions.

Many are the pitfalls to a proper understanding of our liturgy. Its meaning may be lost because it employs words and phrases in a special sense, defined only by the context in which the expression occurs. The allusion to idioms found in Biblical and Talmudic literature may be unfamiliar; the allusions to historical events and personalities are often conveyed by hints, which the uninformed cannot recognize. And one may always confuse symbol with fact, and assume a figure of speech to be a literal truth. Then we suffer a twofold loss; we miss the truth which the symbol sought to convey, and we read a meaning into the passage which was never intended.

The classic editions of the Maḥzor were accompanied by one or more commentaries as indispensable aids to comprehension. The running commentary, whether in Hebrew or Yiddish, lifted the text of the liturgy from vagueness and obscurity; it removed possibilities of misunderstanding; and it made explicit the meanings which were implied or only hinted at in the words of the prayers themselves.

Our edition of the High Holyday Prayer Book attempts to deal with this problem in a similar manner. We have added a commentary to the main text, to elucidate especially obscure points. But a commentary cannot take the place of the text, and we cannot expect the worshiper continually to refer to discussions in footnote in order to comprehend his prayer. A commentary is helpful in clarifying special problems, but it cannot replace a smoothly running text. Frequent references to the commentary would make of the service an intellectual exercise rather than a devotional experience. We have, therefore, tried to make the translation itself lucid and comprehensible, so as to obviate an undue dependence on the commentary.

It may be helpful to specify some of the general concepts that guided us in the translation. Whenever a literal translation of words might obscure the meaning of a text, we disregarded the literal translation in favor of a freer rendering. Vatarem kirem karni in Psalm 92, is in the Hebrew a powerful metaphor. It expresses the Psalmist’s conviction that God would sustain his honor, and protect him against his enemies. But its literal translation, “My horn hast Thou exalted like that of the wild ox,” conveys little meaning. This metaphor arose among our forefathers for whom the wild ox was a familiar sight. The horn was the animal’s principal weapon of defense and attack; it therefore became a potent symbol of strength generally. But we have no experience with the wild ox, and, in its literal translation, this verse creates not clarity but confusion. Our own translation of this verse sacrifices the imagery of the metaphor in favor of a less graphic but a more comprehensible idiom: “Thou wilt sustain my honor.” The Rabbis were aware of the need for avoiding literalisms in translation, as is evidenced by their admonition: “He who translates a verse literally has perpetrated a fraud.”

The Bible and the Prayer Book are more than literature; they are the testaments of our faith. Literalism in translation has occasionally produced serious misinterpretations of the teachings of Judaism. A good case in point is the common translation of ה׳ איש מלחמה, ה׳ שמו in Exodus 15:3. This verse is part of the Song of Moses at the Red Sea, which is incorporated in the daily morning service. It has generally been translated: “The Lord is a man of war, the Lord is His name.” So translated, this verse implies that God delights in war, that He engenders strife. Modern man, who has learnt the horrors of war, shrinks from such a conception of God. He desires to associate God with the quest for harmony and peace. Some of our prayer books have, therefore, omitted this song, or have left this verse untranslated!

The true meaning of this verse becomes clear when we see it in its context, as N. D. Cassuto explains, in his commentary on the Bible (Exodus 15:3, 3:14). Earlier in the narrative, Moses had been assured that God is not indifferent to oppression, that He will take the part of the Israelite against Pharaoh. Indeed, God revealed to him that this characterization of His nature was conveyed by the name יהוה.

God, in other words, is here declared to be a Being who ultimately brings the tyrant down to defeat. He wars against the tyrant, however, because He is just and merciful and will not bear with indifference the oppressions wrought by tyranny. We have, accordingly, translated the verse thus: “The Lord fought against our adversaries; He is a God of justice.”

Our translation of Biblical passages quoted in the Prayer Book, as well as the original liturgical compositions, is in this spirit. It is not a recasting of words or phrases from Hebrew to English. It seeks to convey the meaning underlying the Hebrew idiom. It follows the pattern of the classic translation of the Hebrew Bible, the Targum. It is part translation and part commentary.

Some figures of speech are basic to our liturgy and cannot be disregarded without emasculating the text. We cite the more important of these figures of speech which pervade the liturgy.

The theme of man’s judgment before God is expressed in terms analogous to those of the judicial procedure operative on the human level. God is pictured as sitting on a throne of judgment, reviewing the deeds of all His creatures. He consults a Book of Remembrance which preserves a faithful record of every person’s life. He reaches His verdict after a due consideration of the relevant facts, and He enters His decree in a book. The decree remains tentative until the final hour of Yom Kippur, the time of Neilah, when the gates of the heavenly tribunal are shut. Until then, a person may, through a change of his ways, win a reprieve from a harsh decree. Then the verdict is made final through the imposition of God’s seal upon it.

The conception of a book of life helps to give vividness to the doctrine of human responsibility. It is clear, however, that it must not be taken literally, that it is only a figure of speech. As Maimonides put it ( Guide II 47): “All these phrases are figurative*, and we must not assume that God has a book in which He writes, or from which He blots out, as those generally believe who do not find figurative speech in such passages.”

The reference to angels is frequent in these prayers. One of the favorite themes of the liturgical poets, the paytanim , in their compositions for these days, is the portrayal of man on the one hand and the angelic hosts on the other, each offering his own token of adoration of God. Following the elaborate imagery of Ezekiel, the angels described in these hymns are fantastic, fiery creatures, material in appearance, with wings to aid them in their flight through the universe.

It was Maimonides again who called attention to the figurative nature of these characterizations. Angels, he showed on the basis of his analysis of Scripture, are the cosmic forces through which nature is directed on her course, in conformity with the divine plan at work in the world. They are what the Hebrew name malah implies, emissaries, ministering forces, embedded in the structure of all existing things, through which God governs His world. They are, of course, immaterial and invisible. These references to angels in the piyutim, then, are to be taken as coupling the world of man and the world of nature in the adoration of God.

God is adored when any of His creatures fulfills the purpose of its being. Figuratively, then, we may say, as the Psalmist does, that the heavens, the sky, the day, the night, proclaim God’s glory. They proclaim it without words. It is only in man that life rises to consciousness, self-consciousness as well as God-consciousness, and man’s praise, whether in word, in thought, or through the symbol of some special rite, therefore, becomes an act of conscious adoration. It is in this sense that we have interpreted those piyutim.

The Yom Kippur liturgy includes a verbal reenactment of the Temple rites performed by the High Priest on that day, which centered in the offering of korbanot or sacrifices, and this recitation ends with the plea for the restoration of the Temple and the renewal of its rites. Other portions of the liturgy voice the same hope for the restoration of the Temple and the renewal of the service upon its altars.

These prayers do not imply for us the expected restoration of animal sacrifices. The cult of sacrifices, Maimonides maintained, found its place in Judaism only because this institution was widely prevalent in Biblical times, and the Israelites only reflected the realities of the civilization in vogue during their day. As a means of communion with God, he held the offering of sacrifices inferior to prayer and meditation.

We interpret the term korbanot as we have come to interpret the term avodah. The latter was originally a technical term referring to the cult of animal sacrifices in the Temple. It was later extended to any form of divine service, including prayer. Korban invites a similar treatment. Literally it means “what is brought before God.” Originally it referred to the animal sacrificed. But the animal sacrificed was only a particularization of a more general objective, the expression of devotion to God. The korban, in other words, was, in its essential character, a token of devotion to God.

In a metaphoric sense this term is applicable to any other act expressing our devotion to God. Metaphorically, prayer may, therefore, be equated with korban. Such technical terms taken from the cult of sacrifices as Minḥah, Musaph, Olah and Tamid, have been employed as metaphors for prayer. The technical terms for various sacrifices have even been drawn on as titles for Prayer Books. These include Korban Minḥah, Olat Tamid, Olat Reayah and Seder Avodah.

The metaphoric use of the terms for sacrifices clearly appears in the Bible, in such sentences as זבחו זבחי־צדק, זבחי אלהים רוח נשברה, ונשלמה פרים שפתינו (Psalms 4:6, 51:19; Hosea 14:3). The most dramatic identification of sacrifices with prayer appears in the Talmud, in Beraḥot, Yerushalmi, 4:4: זה שעובר לפני התיבה אין אומר לו בא והתפלל, אלא בא וקרב, עשה קרבנינו.

Animal sacrifices were not ends in themselves, nor is prayer. Both are only tokens. We serve God in deeds taken from the context of life itself, deeds in which we deny ourselves in order to perform God’s will. The rites of worship are a symbolic enactment of the values we cherish, and an affirmation of our commitment to them. The animal sacrifice was such a symbol, and, at the heart of it, so is prayer.

The prayers for the restoration of the Temple express our yearning for that consummation which the prophets portrayed in their visions of the Messianic Age. Included in this vision was always the hope for the rebirth of the Temple in Ẓion, to be, as Isaiah described it, “a House of Prayer for all peoples.” It was to be a religious center for a regenerated Israel and a regenerated humanity from which the word of God would go forth to all mankind.

We cannot know precisely all the elements that will figure in a restored Temple service. We may presume that these services will certainly include prayer and song, since these had already figured as accompaniments to the Temple services even in the days when sacrifices were offered; the act of study may well form part of it; and there may be elements which we cannot envision now but which the creative inspiration of those who will lead our people will fashion in ways altogether novel but expressive of the now realities in their day. And we may presume that as an expression of the continuity of tradition, the renewed Temple service will follow the old, based on the Tamid and Musaph , the former express ing our gratitude to God for His daily blessing, and the latter I ho gratitude for the unique manifestations of His providence that we discern on special occasions.

The Scriptural citation of the sacrifices due on the respective days of the Sabbath and the holy days we deem significant as indications that our tokens of devotion must not proceed with uniform sameness, but must reflect the uniqueness of the particular occasion on which they occur.

Man’s need to come before God in prayer does not derive from the shifting facts of his social history. It is a phase of his permanent condition as a man. Nevertheless, social facts create needs with which we must reckon in our prayers. For long centuries the Jewish people cried for redemption. The yearning for redemption which inspires our prayers calls for more than the restoration of the Holy Land and the return of its exiles. It calls for a return of the Sheḥinah, God’s presence, which languishes in its own exile through the alienation between God and His children. This is the redemption which will usher in the Messianic age. We must still wait — and work — for this consummation. But is it not the rebirth of the people of Israel in the Holy Land part of the divine promise, and its realization part of its fulfillment? We have reckoned with this great fact. We have included, for instance, the prayer on behalf of the State of Israel, composed by Israel’s Chief Rabbinate. It voices gratitude for the restoration and invokes God’s providence on behalf of the Jewish state.

The Yom Kippur liturgy includes a reference to the theme of martyrdom. The Eleh Ezkera is a stirring midrash on the ten sages who died in the sanctification of God’s name during the persecutions under the Roman emperor, Hadrian. Certainly the purpose of such a reference is fulfilled when a classic instance of martyrdom is cited. All martyrs are in a sense included in the heroic faith of the ten. Nevertheless, a generation that suffered six million martyrs needs to give voice to the meaning of its ordeal. It needs this for the sake of its own soul, and it needs it so that this supreme act of martyrdom shall find its sanctification through our bringing its remembrance before God. The Eleh Ezkera follows the recitation of the Avodah, which reenacts the service of sacrifice performed by the High Priest in the Temple of old. The highest offering brought to God is the life of a martyr, but it is we, by our understanding, who can make of the six million the sublime offering. We can do so if the remembrance of those events stirs us to lives worthy of the faith which alone can give meaning to death as well as life. We have, therefore, included the remembrance of the six million in the martyrology section of the Yom Kippur service.

The Hebrew text in this Maḥzor deviates in a number of instances from the generally current text of the service. Some hymns and prayers generally omitted in modern congregations were not included in this Maḥzor. On the other hand, we included a number of new prayers and readings, some taken from the Sephardic Maḥzor and some, the work of contemporary religious poets. In a number of instances we modified the text to conform to alternate versions which seemed more authentic.

The present edition of the Maḥzor is directed to the home as well as the synagogue, and it seeks to cover the total liturgical requirement of the High Holyday season. We have, therefore, included the various rituals which take place in the home during this season of the year, and we have also added the Seliḥot service, recited on Saturday midnight preceding Rosh Hashanah.

The transliterations adopted in this Maḥzor follow general usage. No distinction has been drawn between the ח and the כ since they are identical in sound; both are transliterated as ḥ. In the transliteration of the prayers we followed the Ashkenazic pronunciation, while titles and notes are transliterated according to the Sephardic pronunciation.

May this edition of the Maḥzor help the modern Jew to heed more earnestly the call to penitence proclaimed by the Days of Awe.

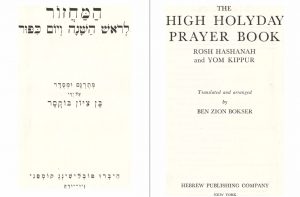

BEN Ẓion BOKSER

Forest Hills , N.Y. September 1959.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

I acknowledge my indebtedness to the distinguished rabbis and scholars who served on the Committee that cooperated in the preparation of this Prayer Book. Their counsel, their criticisms, and their numerous suggestions, proved invaluable and contributed much toward the consummation of this project.

The Committee that cooperated in the preparation of this Mahzov was initiated by a resolution of the Executive Council of the Rabbinical Assembly, voted at its meeting on October 31, 1957. It functioned as a subcommittee of the Joint Prayer Book Commission of the Rabbinical Assembly of America and the United Synagogue of America.

All ideological issues were resolved in consultation with the Joint Prayer Book Commission of the Rabbinical Assembly of America and the United Synagogue of America, and subsequently confirmed by the Executive Council of the Rabbinical Assembly.

I am grateful to the members of the Joint Prayer Book Commission, especially to its Chairman, Rabbi Max Arzt, for assistance and cooperation. Rabbi Arzt’s initiative was most helpful in resolving many of the problems which were encountered on the way, and I am deeply grateful to him.

I express my thanks to Ḥazzan Max Wohlberg who composed the music for severalhymns in English which appear in this Maḥzor. This music is available in a supplement to the Maḥzor. We believe that its use will add to the enrichment of the High Holyday service.

Rabbi Aaron Blumenthal, Rabbi Wolfe Kelman, Rabbi Isaac Klein and Rabbi Bernard Segal accorded me many courtesies, and they shared in the conversations which led to the appointment of the committee that cooperated in this work. I express to them my thankfulness and my appreciation.

I also express my sense of gratitude to a number of scholars, colleagues and friends, who guided me in the solution of various problems with which I turned to them: Dr. Hillel Bavli, Dr. Boaz Cohen, Dr. H. Dimitrovsky, Dr. A. M. Haberman, Dr. Shalom Spiegel, Rabbi Jacob Agus, Rabbi Josiah Derby, Rabbi Benjamin Englander, Rabbi Herman Kieval, and Rabbi Simon Kramer. To Rabbi Pinchos Chazin, Rabbi Arnold Lasker and Rabbi Benjamin Teller, I am thankful for aid in reading the proofs.

I am grateful also to Dr. Nahum N. Glatzer for permission to quote from his book, Franz Rosenzweig: His Life and Thought and to Dr. Hillel Bavli for permission to use his poem Tavalnu Et Besarenu. Dr. Bavli also composed the Hebrew version of the introductory statement to the poem.

I acknowledge my indebtedness to Rabbi Robert Gordis. In our many discussions of problems in the liturgy, he often challenged me to reexamine my own views and thereby led me to a deeper understanding of the issues involved.

Mr. A. G. Kraus, Executive Director of the Forest Hills Jewish Center, proved, as ever, a helpful adviser on various problems with which I turned to him.

My wife was patient and, as always, an unfailing guide in all aspects of this work. My daughter and son, too, shared in this project and I voice my gratitude to them on the occasion of its completion.

Beyond all else, I voice my gratitude to Almighty God who privileged me to bring to completion an undertaking that often seemed beyond the reach of my hands.

BEN Ẓion BOKSER

EDITORIAL COMMITTEE

Appointed by the Rabbinical Assembly of America and the United Synagogue of America

Rabbi Aaron Blumenthal

Temple Emanuel, Mount Vernon, N. Y.Rabbi Arthur Chiel

Genesis Hebrew Congregation, Tuckahoe, N. Y.Rabbi Myron Fenster

Jewish Center of Jackson Heights, N. Y.Rabbi Solomon Goldfarb

Temple Israel, Long Beach, L. I., N. Y.Rabbi Harry Halpern

East Midwood Jewish Center, Brooklyn, N.Y.Rabbi Judah Nadich

Park Avenue Synagogue, New York, N. Y.Rabbi Max J. Routtenberg

Temple Bhiai Sholom, Rockville Center, L. I., N. Y.Rabbi Edward T. Sandrow

Temple Beth El, Cedarhurst, L. I., N. Y.Rabbi Morris Schussheim

Beth Israel, Providence, R. I.Rabbi Seymour Siegel

Lecturer in Theology, Jewish Theological Seminary of America.Rabbi Marvin S. Wiener

Director, National Academy for Adult Jewish Studies, United Synagogue of America.Hazzan Max Wohlberg

Malverne Jewish Center, Malverne, L. I., N. Y.

“📖 המחזור לראש השנה ויום כּיפּור (אשכנז) | HaMaḥzor l’Rosh haShanah v’Yom Kippur, translated and arranged by Rabbi Ben-Zion Bokser (1959)” is shared through the Open Siddur Project with a Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication 1.0 Universal license.

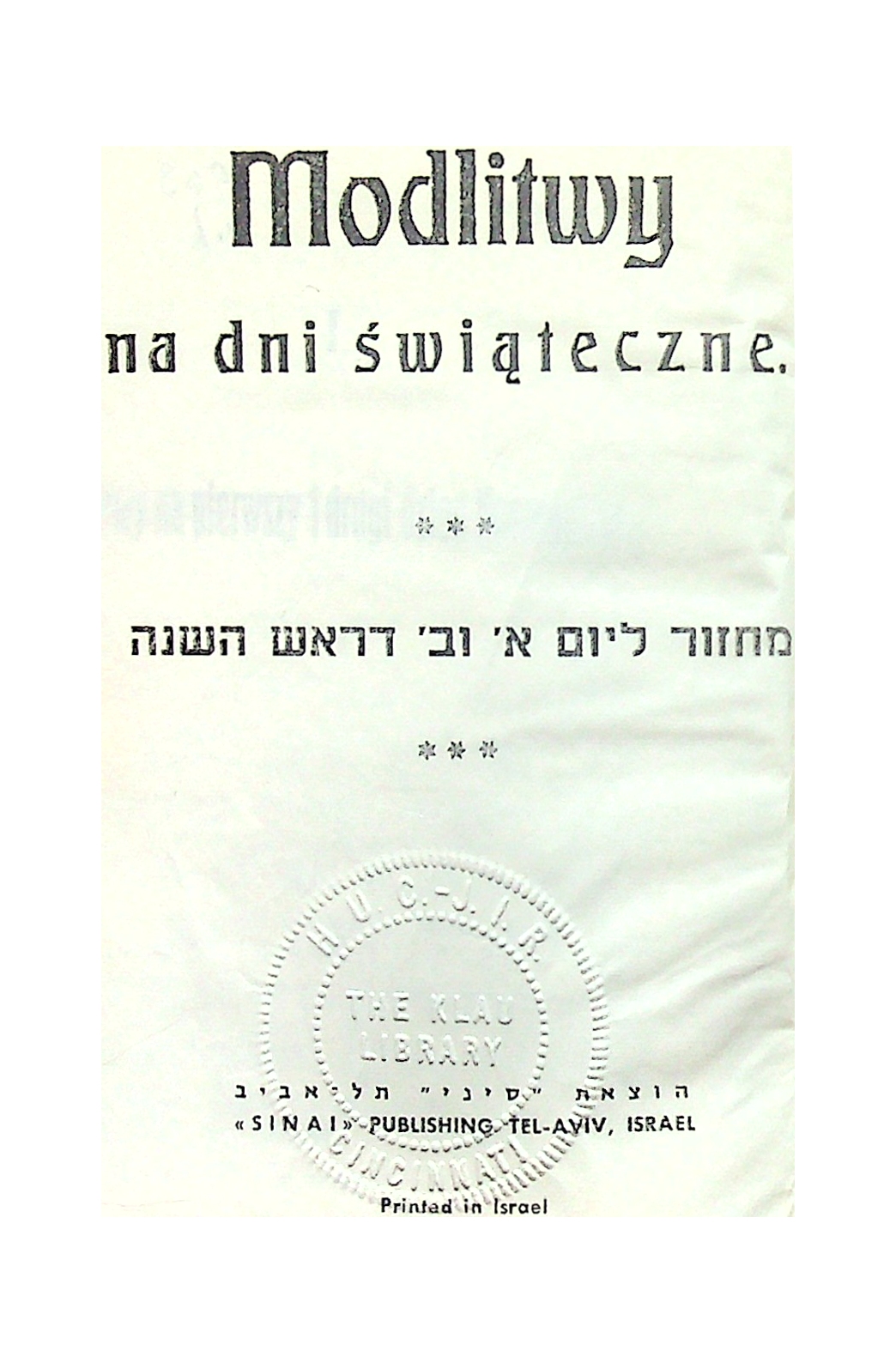

![Maḥzor haShalem l-Rosh haShanah - Nusaḥ "Sfard" [Ḥassidic] (Paltiel Birnbaum 1958) - title page](https://opensiddur.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/title-birnbaum-rh-sefard-mahzor-1958.png)

Leave a Reply