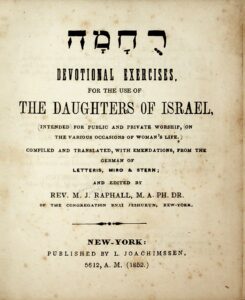

רֻחָמָה (Ruḥamah): Devotional Exercises for the Use of the Daughters of Israel (1852) by Rabbi Morris Jacob Raphall (1798–1868) is one of the first collections of teḥinot published for an English speaking audience. The work, commissioned by Louis Joachimssen (1791-1870),[1] Louis (also Lewis, or simply L.) Joachimssen was an attorney based in New York. includes translations of prayers selected from popular collections of tehinot in German by Yehoshuah Heshil Miro (Beit Yaaqov: Allgemeines Gebetbuch für gebildete Frauen mosaischer Religion, 1829/1835), Menaḥem Mendel Stern (Die fromme Ẓionstochter, 1841), and Meïr Letteris (Taḥnune bat Yehudah, 1846). According to Raphall in his introduction, “I did not limit my task altogether to that of a compiler… in many instances I found it necessary to add emendations.” In addition to the works he translated, I believe he may also slipped in a prayer of his own, “Exercise for a Wife who is married to an irreligious Husband” — which I have not located in any edition of the collections of Miro, Stern, or Letteris printed before 1852. (It’s possible it was translated from another unattributed source; if you know more, please leave a comment or contact us.)

This collection of teḥinot follows the publication in French of אמרי לב (Imrei Lev): Prières D’un Cœur Israélite (1848) by Jonas Ennery and Rabbi Arnaud Aron — and precedes the publication of Stunden der Andacht (1855), Fanny Neuda’s collection of her teḥinot written in German. All of these express a movement of tkhines literature beyond an audience of vernacular Yiddish readers and into a world of emancipated Jews more fluent in the language of the modernizing states in which they lived.

Besides Imrei Lev, 1852 saw the publication of two other collections of teḥinot in English: תחנות בנות ישראל (Teḥinot Banot Yisrael): Devotions for the Daughters of Israel by Marcus Heinrich Bresslau (an old colleague of Raphall’s from his time in London), and Miriam Wertheimer’s Devotional Exercises for the Use of Jewish Women on Public and Domestic Occasions — both of which were printed in England. Ruḥamah was the first collection of teḥinot published in the United States and the first prayerbook published exclusively for use by Jewish women. (The first prayerbook — a hymnal — comprised largely of poems by a Jewish woman was Hymns Written for the Service of the Hebrew Congregation Beth Elohim, Charleston, South Carolina by Penina Moïse et al., 1842.)

This work is in the Public Domain due to its having been published more than 95 years ago. This digital edition was prepared by Aharon Varady and derived from page images he took of a volume in the collection of the HUC-JIR Klau Library (Cincinnati, Ohio) for the Open Siddur Project. (Thank you!)

Southern District of New York, s.s.

Be it remembered, That on the tenth day of March, Anno Domini 1852, L. Joachimssen, of the said District, has deposited in this office the title of a book, the title of which is in the following words, to wit: רֻחָמָה “Devotional Exercises for the Use of the Daughters of Israel, Intended for Public and Private Worship, on the Various Occasions of Woman’s Life. Compiled and Translated, with Emendations, from the German of Letteris, Miro, & Stern; and edited by Rev. M.J. Raphall, M.A. Ph. Dr. of the Congregation Bnai Jeshurun, New York.”– The right whereof he claims as proprietor–In conformity with an act of Congress, entitled “An Act to amend the several Acts respecting copy-rights.”

Geo. W. Morton,

Clerk of the Southern District of New York.Abraham G Levy, Stereotype and Letterpress Printer, 183 William street, N.Y.

[DEDICATION]

For The Daughters of Israel “More precious than gold, more pure than refined gold,”

These devotional exercises, intended for their use, as maidens, brides, wives, mothers, and on all other occasions, of joy, or of trial, incidental to their sex, for private or public devotion, are respectfully dedicated, by their sincere well-wishers, the Editor and the Publisher.

PUBLISHER’S PREFACE.

The want of a suitable collection of Devotional Exercises, in the vernacular tongue, for the daughters of our people, has long been felt and lamented by many who, like myself, are fathers of families. In Europe the want has been abundantly provided for, especially in Germany, where not only the old Jidish-Deutsch Techinoth “Supplications” were diligently and devoutly used by the mothers of by-gone generations; but where more modern works, adapted to the wants and civilization of the present age, have been published and passed through numerous editions.

Discoursing on this subject with my Reverend friend, Dr. Raphall, he agreed with me, that in the absence of any Hebrew educational institution for females in this country; and under the consequent impossibility of their receiving adequate instruction in the Hebrew language, or in their religious duties; a work that should at once satisfy their hearts and their minds, would be a most valuable boon to them. “On this hint I spake,” and proposed to him to undertake the editing and translating of a compilation of Devotional Exercises, to be selected from the works of Letteris, Stern, and Mira;[2] Meïr Letteris, Menaḥem Mendel Stern, and Yehoshua Heshil Miro. the best, and most approved, at present, in existence; which I offered to print and to publish at my own expense. He entered into my views, and the result of his labours is now placed before the public.

It does not become me to speak in praise of a work published by myself; nor does the Editor need my approbation to recommend him to public favour. But I feel that this book will indeed meet and satisfy the want of which I have spoken; and I congratulate myself that a work undertaken, not for great gain, but for, great public utility, should have fallen into hands so well able to do it justice. That the pious daughters of Israel will hail this little book with pleasure and thanks, is my flattering hope; that it may promote religious feeling, and uphold religious spirit and observances among them, is my fervent prayer.

L. JOACHIMSSEN, Publisher.

TRANSLATOR’S PREFACE.

No prayer book at present in existence, and in use with any religious community, can sustain a comparison with the Hebrew prayer book of the Portuguese, as well as of the German ritual. Sacred, from the authority with which it originated; venerable from its extreme antiquity; sublime in its language; pious and holy in its aspirations; simple and pathetic in its petitions; the living representative of our nationality; the last asylum and guardian of that holy tongue in which Moses received the Law, and the prophets delivered their inspired predictions; but which the daily use of the Hebrew prayer book, alone, preserves and perpetuates among us. Such is the character and excellence of this glorious monument of our ancient literary eminence, and of the true religious feeling that prevailed in Israel—not only while the temple of Jerusalem stood erect in the fullness of its beauty and holiness—but likewise long after that sacred structure had been laid in ruins; and during the many dark ages of dispersion and persecution, when, of all its former glories, Israel only preserved the Law of God and the Hebrew prayer book, to keep alive the memory of past greatness, and the hope of its restoration. And that Hebrew prayer book, which has so long been the ladder that, placed on earth, reaches up to heaven; and by which the wants, the fears, the thanksgiving, of Israel, ascend and plead before the mercy-seat of the God of Abraham, while hope, comfort, and blessing from on-high return to them—this prayer book, may it never be expelled from our public and private worship; may it never be superseded in our synagogues or our houses; may it never be forced to yield to the would-be improvements of innovators, whose productions, however good in intention, however approved of by any particular congregations, would nevertheless destroy that bond of union and of brotherhood among Israelites, which the Hebrew prayer book now is, has so long been, and always will remain.

But whilst thus the pre-eminence and extreme importance to all Israelites, of the Hebrew prayer book must be generally acknowledged, and by no one with more heart-felt conviction than by myself; the necessity for some auxilliary or supplementary devotional exercises, was felt at an early period; and especially by that sex whose religious emotions are the most lively, while their means of religious instruction is generally the most limited. The Hebrew prayer book is a great national work, undertaken and carried out at times when the entire nation of Israel—identified in hope, in sentiment, and in suffering— disdained every selfish feeling; and all-absorbed in the general and public welfare, scarcely left any room for individual aspirations, or the personal outpourings of a prayerful spirit. Accordingly, the prayers offered by Israelites, in their public and private worship, are offered in the plural number; and this is so true, that with two or three exceptions, of which the Elohai Neshamah, “My God! the soul that thou hast placed within me,” and the thanksgiving for being born free, a man and an Israelite, are the principal; none of the prayers, not even the eighteen benedictions and the Abinu Malkenu, ever contain the pronouns, “I,” “me,” “mine;” but universally have, “we,” “us,” “our.” It is a beautiful idea, this total abnegation of individuality, and one all-absorbing nationality, in our communing with God; an idea which enables us justly to appreciate the mental and spiritual calibre of the inspired and highly-gifted men, by whom these prayers were framed. Verily “there were giants on the earth in those days.” That high-souled generation is passed away, and has not left many representatives among the men of Israel, who continue to use that prayer book.

With woman, the case is different; at all times she has found, and she finds her world within that charmed and charming circle of domestic duty and domestic bliss, of which, as wife and as mother, she is the presiding and guardian genius. And though her religious aspirations are generally more pure, more heartfelt than those of man; though there is no act of magnanimity, of patriotism, of self-sacrificing devotion, of which woman is not capable in an equal, and even a superior, degree to man; yet in her ordinary and tranquil state, and while her feelings hold. “the even tenor of their way,” those who are dearest to her heart will be uppermost in her mind. Whilst, therefore, her individual home is the principal sphere of her activity and solicitude, it is but natural, that in her communion with her God, she should be anxious to give utterance to those feelings which that solicitude inspires; and that as prayer is one of the chief as well as of the noblest necessities of her woman’s nature—she should desire to be furnished with forms of devotion adapted to her individual wants, and to those occasions of joy or of trial that are peculiarly incidental to her sex. So it was in the days of Hannah, so it is now. Accordingly, wise and pious mothers in Israel, from time to time, composed Techinoth, supplications, for their own use and that of their sisters in faith. They composed them in the language most familiar to them—their own vernacular tongue—in which they could best give vent to their feelings. And these Techinoth met with the full sanction and approval of the wise and learned Rabbins and teachers in Israel, under whose auspices they were collected and published in a book, that during several ages was cherished with the utmost veneration by the daughters of Ẓion. But gradually these original Techinoth become superannuated, and ceased to be adapted to the wants which advancing mental culture, and superior education, had created. They were, therefore, superseded by more modern productions, especially in Germany; a country which, since the days of Mendelsohn, is the great native home of Jewish literature. When my friend, the publisher, obtained my consent to assist him in bringing out the present compilation, he placed before me three, the best and most generally approved collections, of German Devotional Exercises; that by Letteris, which has passed through three—that by Stern, which has. passed through four— and that by Miro, which has passed through two editions ; a number of works and of editions which (independent of other similar works not so generally diffused) plainly shows the favour with which these Exercises are received by the daughters of Israel in Germany.

But if such is the case in that country, where institutions for the religious instruction and training of Jewish females are numerous, whilst their pecuniary means are but limited; and where, nevertheless, such books of devotion are felt to be one of the great wants of the age. And where this want prevails to such a degree that even amidst the turmoil of the last few years of revolution and of re-action, three leading works on the same subject have been so eagerly received by those for whom they were written, that nine large editions have been exhausted, and fresh ones (as I understand) are in preparation. How much greater must be the want of such Exercises in this young country, where Hebrew educational institutions for both sexes are in their infancy, and where, while boy’s schools are few, girl’s schools can scarcely be said to exist; but where nevertheless woman’s pure heart is unchanged—glowing with the same pious aspirations, and longing for the same prayerful outpourings, which these Exercises enable their German sisters to gratify. Accordingly I expect that my friend, Mr. Joachimssen, who first suggested the idea of this compilation, and who publishes the work on his own responsibility, will be rewarded by the favour and thanks of the daughters of Israel in America, for whose use it is especially intended. My own claims on their gratitude are not very strong, since the principal part of my work consisted merely of selecting and translating. Nevertheless I did not limit my task altogether to that of a compiler. For in many instances I found it necessary to add emendations, which I trust will not be deemed the least useful or interesting portion of the book; inasmuch as they consist of reflections, conveying instruction, on the principal points of our faith, and on our observances; which the German authors thought themselves entitled to dispense with, as properly belonging to the school, and in which, therefore, they had a right to assume that most of their readers were well-grounded. But which, in this country, must obtain a place in devotional exercises, as many of these, without such instruction, would be very imperfect. And I have called the collection Roochamah—“She who obtains mercy,”—(Hosea 2:25) in the fervent hope, that the daughters of Israel—so obedient as children, so pure as maidens, so faithful as wives, so affectionate as mothers, so exemplary in every condition of life—will obtain mercy from the God of mercy, when with pious accents they give utterance to their pious feelings; and address to him supplication and worship, that flow alike from their heart and their mind, and that satisfy alike their faith and their understanding. May it be the will of Him “who is good, and who doeth good,” that this little book, the firstling of my pen in this my new country, may be productive of good; that it may lead many a gay votary of pleasure to think; that many a worldly mind it may reclaim; that many a pious soul it may confirm in faith; that many a stricken heart it may conduct to the neverfailing source of consolation; of the strength which sustaineth, of the hope which faileth not—even God, his holy Law and Word! Amen.

MORRIS J. RAPHALL.

INDEX

Morning Exercise

Evening Exercise

Exercise on going to Bed

Exercise for Support and Direction

Exercise for the 1st Day of the Week

Exercise for the 2nd Day of the Week

Exercise for the 3d Day of the Week

Exercise for the 4th Day of the Week

Exercise for the 5th Day of the Week

Exercise for the 6th Day of the Week

Exercise on taking Chalah on Sabbath Eve

Exercise on kindling the Sabbath Lights

Public Worship.

On entering the Synagogue

Exercise for the Sabbath [№1]

Another Exercise for the Sabbath [№2]

Another Exercise for the Sabbath [№3]

Exercise when the Ark is opened and the Law taken out

Devotional Exercise on the Sabbath when the New Moon is proclaimed

Exercise on quitting the Synagogue

Exercise on a Fast day

Exercise for the 9th day of Ab

Exercise for the 1st days of Passover

Exercise for the last days of [Passover]

Exercise during the Sephira

Exercise for the Feast of Weeks (Shebuoth)

Exercise for the Feast days of Tabernacles

Reflections on pronouncing the Benediction over the Loolab [Palm-branch]

Exercise on the day of Willows, Hosannah Rabbah

Exercise for a person enceinte on the Hosannah Rabbah, before pronouncing the Benediction of the Loolab

Exercise on the Festival of the Law [Simchat Torah]

Exercise on the Eve of the New Moon [Rosh Hodesh Ellul] the last month of the year

Reflection for the first day of Selichoth

Exercise for New-Year’s Eve [Ereb Rosh Hashanah]

Exercise for New-Year [Rosh Hashanah] on taking the Rolls of the Law from the Ark

Exercise previous to the blowing of the Shophar [Cornet]

Exercise on Rosh Hoshanah [Moosaph]

Exercise for Rosh Hoshanah and Yom Kippoor, while the Hazan prays (Alenu Leshabeach)

Exercise on the Rosh Hoshanah, during the principal portion of the Moosaph prayers

Exercise for the Penitential days

Exercise for the Evening of Yom Kippoor

Morning Exercise for the day of Atonement [Yom Kippoor]

Exercise during the Moosaph, for the Yom Kippoor

Exercise for the Afternoon Service [Minchah] for the Yom Kippoor

Exercise for the Closing Service [Neilah] of the Yom Kippoor

Exercise when the Cohanim ascend the Doochan to pronounce the Benediction

Exercise in Memory of the Dead [Haskaroth Neshamoth or Haskabah]

Another Exercise on the same subject

Exercises for Special Occasions.

Exercise for a Maiden in the House of her Parents

Exercise for a Fatherless and Motherless Orphan Maiden

Reflections of a Bride

Reflections of a Bride before the Marriage Ceremony

First Exercise for a Wife on finding herself enceinte

Exercise for a more Advanced Stage of Child-bearing

Exercise for the approach of Accouchment

Exercise after Safe Delivery

Exercise for a Mother whose son is being Circumcised

Exercise for a Mother who comes out of her Confinement

Exercise for a Mother on a Sabbath day on which any particular solemnity takes place, as a Circumcision or Bar Metzvah. [a son attaining his thirteenth year,] or the naming of a daughter

Exercise for a Childless Wife

Exercise for a Wife to invoke a blessing on her Husband’s Industry

Exercise for a Wife who is Unhappily Married

Exercise for a Wife who is married to an irreligious Husband

Exercise for a Wife whose Husband is on a Journey

Exercise in Heavy Sickness

Exercise on the illness of those nearest and dearest

Exercise and Thanksgiving for health restored

Exercise for a Widow

Exercise for the Anniversary of a Parent’s Decease [Yahr Zeit]

Notes

“📖 רֻחָמָה | Ruḥamah: Devotional Exercises for the Use of the Daughters of Israel, by Rabbi Morris Jacob Raphall (1852)” is shared through the Open Siddur Project with a Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication 1.0 Universal license.

Leave a Reply