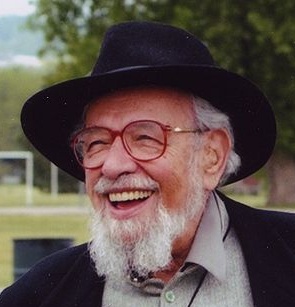

Blues for Challah 2012 at Isabella Freedman Jewish Retreat Center (credit: Rachel Molly Loonin and The Whole Phamily )

I believe that even those who actively dislike the Grateful Dead, or always happily ignored them, will find ideas worth considering in this comparison.

“I guess they can’t revoke your soul for trying.” – Robert Hunter

Some years ago, my husband and I dragged our kids (then 11 and 13) to see the Dead. The kids asked why the folks in the parking lot were staying outside, even though the concert was scheduled to start: “How do they know when to go inside? Or, is the band waiting for them?”

My husband, a non-Jew, noted that he was often similarly mystified by worship services: “How do they know when to it’s time for….?”

Not long after that I was part of a small ḥavurah gathering waiting for a minyan, and we got to talking about when we might expect various regulars. This started me thinking about when, how and why Jews show up to services. I realized my husband’s sentiment about worship services – like my kids befuddlement about Dead concerts – is shared by many Jews, even regular service-goers….

Over the years, I’ve been thinking about ways that Jewish text and worship and the Grateful Dead parallel one another. The result is this chart [below].

How the Grateful Dead, Jewish Text and Worship Explain One Another and Raise Interesting Questions | |||

(Grateful) Dead | Jewish Text/Tradition | Additional Note(s)/Questions | |

The (Grateful) Dead frequently took the stage without greeting and began such extensive set up that the uninitiated might assume that A) they were watching roadies or that B) the concert would consist of endless sound checks. Sometimes the final chords of one song flowed directly into the next; other times, stretches of equipment fiddling and/or improvisation separated songs. | Sanhedrin 2a: “…But how do we know that a congregation consists of not less than ten? It is written, how long shall I bear with this evil ‘edah. Excluding Joshua and Caleb, we have ten….” Bible verses appear without quotation marks, discussion seems always to be already in progress. Related points follow in places; apparently endless digressions separate other points in an argument or exposition. | In some Jewish traditions, individuals participate in prayer largely on their own, expecting to join in unison prayer only for the barchu, kaddish, repetition of the Amidah and a few other spots. A visitor unfamiliar with this worship style might find it hard to participate. | If a prayer leader – or the person in the next seat -announces the service progression with care and someone regularly tells you “what page we’re on,” is that a sufficient clue as to what others are doing and/or how you might experience anything in the service? |

Long sound checks, tendency to drift into individual or collective equipment adjustment, and habit (at least in older days) of barely acknowledging the audience were not irrelevant to the band’s purpose (cf. acid test history). The Dead interact with one another, relating to an audience without addressing music TO it. | Elements of style visible in San 2a above -weaving together of biblical sources, use of narrative Torah to explain a practicality, like the minimum size of a “congregation” – are not irrelevant to understanding either the Talmud or the passage from Numbers. The ancient rabbis and the texts are in a conversation with one another, relating to future generations but not speaking TO us. | Worship style is not irrelevant to how participants view what is happening in the service: With few exceptions – Humanist prayer, e.g. – the main siddur text is part of an ancient, on-going conversation between Jews and God, not written TO users. | How do we – as individuals and as a congregation – view the service? How much is internally directed? focused on wider concerns? relating to others present? to “Israel”? to/for God, however defined? Do these elements vary by person? gathering? moment? |

Are extended improvs and long drumming sessions time for a break or the point of a concert? Is melody just a launching point for the “real,” improvisational music? Or are instrumentals sometimes just pauses, perhaps unduly long, in the melody? Which is “digression” and which is essential? | (Sanhedrin 2a continued) “…excluding Joshua and Caleb, we have ten, and whence do we derive the additional three?… ” The passage returns to what is ostensibly the “main discussion,” of how it is known that 23 men are needed for a small Sanhedrin. | It’s the “digression” here that proves relevant to this week’s portion and the definition of a minyan. Similarly, moments after a chant and spaces between words are as crucial as carefully crafted siddur text. | We can sing prayers, chant, dance; re-order or re-focus the prayers; write new ones; share intentions. Sit silently. What is essential – for each of us and for us as a group -for prayer to “work”? |

At ticket time, many best seats for a (Grateful) Dead concert were empty while true Deadheads stayed outside, doing business and partying, until the concert began in earnest, and/or the Dead did not really get going until the seats filled. So, one might ask: How did anyone – band or fans – ever know when it “was time”? | In Shelach-lecha, the People believe the spies’ “evil reports” about the Land and refuse to “go up.” This ends in death and disaster. Then, after being told that they will now die in the desert for failure to take the Land immediately, some make a last ditch effort to “go up” (14:40ff). This ends in disaster and death. How did the People (and God) learn the right time? Did they? Were 40 years enough? Too much? | Sefat Emet (R. Yehuda Aryeh Leib Alter, 1847-1905) identifies the last-ditch aliyah attempt with yearning for a kind of ungrounded, self-serving spirituality. In comparison, he urges: Before doing anything, you have to offer up your soul as an emissary, gathering together all of your desires, in order to negate them, so that you can fulfill only the will of God. – 1998 trans. w/commentary by Arthur Green, Shai Gluskin Can we manage this on a collective scale: In group prayer? In group decision-making? How? | |

Despite lack of introductions on stage and absence of album liners, many fans could identify current and past band members, knew each’s musical history, and often referred to band members by first name as though speaking of near neighbors or cousins… . ..and just when you thought you had the band identified, the person in the next seat would begin muttering, “I miss Donna,” or “It’s not the same without Pigpen.” | Arachin 15a “It was taught: R. Eleazar b. Perata1 said, Whence do we know [the power of an evil tongue]? From the spies: for if it happens thus to those who bring up an evil report against wood and stones, how much more will it happen to him who brings up an evil report against his neighbour!.. .Perhaps it is as explained by R. Hanina b. Papa2; for R. Hanina b. Papa… Rather, said Rabbah3 in the name of Resh Lakish4…” | 1] 2nd--3rd Century CE (third generation Tanna); 2] 3rd -4th C (Fifth generation Amorim, post-Tannaim); 3] of priestly family, Rabbah bar Bachmani 3rd-4th C, (third generation Amora); 4] Shimon ben Lakish, 3rd C (early Amora) former gladiator, brother-in-law of R. Yohanan bar Nappaha | More fanatical Deadheads believe(d) that being a worthy listener required knowing, e.g., which years Donna Jean and Keith Godchaux were with the band, who wrote and sang which songs, etc. Similar claims are sometimes suggested about Jewish learning or prayer. |

Some histories of the band long known as “the Grateful Dead” might begin with the first concert in 1965, but many would say you have to start with the Warlocks or Mother McCree’s Uptown Jug Champions or when band members met in 1962 or first learned music… | Like San. above, all Talmud tractates begin on page 2a. The first words of the first tractate -“From what time may one recite the evening Shema?” – assume so much that it’s clear the conversation is already in progress. “2a” is a printer’s convention, yes, but also a reminder that no amount of learning brings us to page 1. | Taking as a given that we’re, none of us, yet on page 1 can be freeing, an invitation to jump in and experience Jewish learning or prayer -or even a (Grateful) Dead recording – wherever we are. | On the other hand, failing to recognize that we’re jumping into an on-going enterprise, extending beyond our own lives and times, can narrow the experience into nonsense and noise. |

“Let the words be yours. I’m done with mine.” – John Barlow, “Cassidy,” 1972 …no more Grateful Dead songs will be written. It appears that after forty years, we can say, truly and finally, that the words are yours. That we are done with ours. (Not that they ever really belonged to anyone in the first place.) – John Barlow, Complete Annotated Grateful Dead Lyrics, 2005 Lyricist Robert Hunter says he originally didn’t publish lyrics “so people could dub their own mishearings, adding a bit of themselves to the song.” A song is only ever fully realized when it belongs to everyone whose language it inhabits. – Robert Hunter, Annotated Lyrics | The reader, in his own fashion, is a scribe…. the Revelation [is a] word coming from… outside, and simultaneously dwelling in the person who receives it….some of its points would never have been revealed if some people had been absent from mankind…. the multiplicity of irreducible people is necessary to the dimensions of meaning; the multiple meanings are multiple people. – E. Levinas, Beyond the Verse, p.131 The relationship that links Israel to the Torah is revealed in the very name Israel. These five letters are the initial letters of the words: nnn^ nvmK man ‘There are 600,000 letters in the Torah. Each Jewish soul takes inspiration from one of the letters of the torah, which remains his own forever. – Eliyahu Munk, The Call of the Torah Ex. 12:37 | Teachings at left are from a recent Jewish Study Center class taught by Sheldon Kimmel, Adas Israel member and former Fabrangener, with whom I studied for years. Levinas (1906-1995) was a French Talmudist-philosopher. Munk is contemporary orthodox scholar. We are essential to Torah, but so are other “scribes.” Isolating a bit of Torah – without reference to other letters’ inspiration; without including other Revelation participants over the ages – is like relating to only one instrument (>>) in a band. Even solos exist in a wider musical context. | To enjoy the Dead, it is not necessary to know that Sweet Jane, who “lost her sparkle… living on reds, vitamin C, and cocaine,” echoes an old radio commercial: “Poor Millicent [who] never used Pepsodent, her smile grew dim and she lost her vim.” It’s fun but not fundamental that Bertha, who is begged “on bended knees… don’t you come around here anymore,” was not human, but an off-kilter, room-cooling fan that moved when on. However, to refuse to listen to anything except the drums or a single guitar, e.g., would completely distort the music. |

For many years (even now?), there were folks who maintained that the Grateful Dead would never be as good as they were when Ron “Pigpen” McKernan was piano player and front man (he died in 1973, before the height of the band’s popularity). There were a number of changes over the years, mourned with more or less passion. Finally, many found it heretical to consider the band’s continuation after Jerry Garcia’s death. But “the Dead” did tour for years. (Long known informally as “the Dead,” they formally dropped the “Grateful” after Garcia’s death in 1995.) | Moses received Torah from God at Sinai. He transmitted it to Joshua, Joshua to the elders, the elders to the prophets, the prophets to the members of the Great Assembly… (Avot 1:1) Shemayah and Avtalyon received the tradition from [their teachers]. Shemayah taught: Love work; hate positions of domination; do not make yourself known to the authorities. Avtalyon taught: …be careful of what you say lest you be exiled by the authorities…Hillel and Shammai received the Torah from them. Hillel taught: Be a disciple of Aaron, loving peace and pursuing peace…Shammai taught: Make the study of Torah your primary occupation… (Avot 1:10-15) | “In simultaneously placing each rabbi within the chain of transmission and giving each rabbi his own voice, Pirkei Avot makes an essential statement about the nature of Torah and interpretation: Even though each generation interprets and applies the Torah according to the needs of the time, these interpretations have the authority of laws given by God at Mount Sinai.” – Rabbi Jill Jacobs | There is a tradition (ref.?) that each new generation, further from the certainty of Sinai, is less authoritative than the previous. But there is a tradition, too, that all Israel were at Sinai (cf. Jacobs, left). And we have messianic hopes for a better future. “Hashkiveinu: Return us to You as in days of old,” is at once backward- and forward-yearning, i.e., a cry to (re-) realize God’s rule in our lives, speedily and in our day. |

It’s like [Bob] Dylan’s “Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door”[1] I wasn’t at Woodstock either and never saw Dylan live, but I did hear the Dead perform this song, and so reading this comment led to last year’s drash “You didn’t have to be there: Sinai, Prayer and the Grateful Dead,” (Mattot 5771, July 2011), now on my blog, “Song Every Day,” http://wp.me/ptnpJ-Kg — one of my favorites from Woodstock. Well, I wasn’t at Woodstock and I’ve never been in a hangman’s noose waiting for the trap door to fall out, so I can’t sing that song? No, we just jump in because it touches us. So part of Jewish prayer is allowing ourselves to say, “These are the words of my people, and I’m connecting to them.” People who weren’t at Woodstock claim it as their music, their generation, as if they were there. I can sing the words of my ancestors and claim Sinai. – Shawn Zevit, in Making Prayer Real by R. Mike Comins, 2010 | |||

Back when folks living or traveling together had to negotiate group music choices, the Dead were vetoed as background music. This included a prohibition on starting a song without time for the whole thing: Listen or don’t! Some purists rejected recordings: old ones were inferior in clarity, obscured lyrics, and failed to translate the gestalt. A guide could accompany you. Recordings – harumph! -might prepare you. But, ultimately, the Dead had to be experienced for oneself. | The episode of the spies and the failed attempt to take the Land are followed (Num. 15) by ritual commandments, some specific to the Land and some – tzitzit and taking challah –still practiced. These, according to some midrashim, are offered to the People as a future treat – they will be undertaken later -and so an indication of forgiveness. A related explanation: these rituals meet the People where they are with an opportunity to fulfill “na-aseh v’nishmah [We will do and we will obey/hear/understand]” (Ex. 24:7). | Sefat Emet notes that the spies are told to “tour [nm v’yatiru] the Land of Canaan.” Relating this verb to “Torah mn,” he says the spies were confused about the role of Torah in mundane life. After the failed attempts to “go up,” God offers day-to-day Torah, functional ways to “go up.” Taking challah (removing a portion [for the priests] when baking a certain amount of dough) elevates the ordinary task of baking. Tzitzit would allow Israelites to see, in everyday life, what they failed to know directly. “…remember and perform them, tizk’ru v’asitem [all my commandments and be holy to your God” (Num. 15:40) | |

The deeper experience is one that wells up from within, transforming consciousness itself from the inside rather than confronting it with sound or sight of that which still manifests itself as “other.” – Sefat Emet, The Langauge of Truth, 1998 trans. with commentary by Arthur Green and Shai Gluskin | |||

This was originally presented as part of a d’var Torah on parshat Shlaḥ (Numbers 13:1-15:40) at Temple Micah in Washington, DC.

Comments are encouraged.

Please visit “A Song Every Day,” for more thoughts on Jewish text and prayer.

Notes

| 1 | I wasn’t at Woodstock either and never saw Dylan live, but I did hear the Dead perform this song, and so reading this comment led to last year’s drash “You didn’t have to be there: Sinai, Prayer and the Grateful Dead,” (Mattot 5771, July 2011), now on my blog, “Song Every Day,” http://wp.me/ptnpJ-Kg |

|---|

“בלוז פון חלה | How the Grateful Dead, Jewish Text, and Worship Explain One Another and Raise Interesting Questions, by Virginia Spatz” is shared through the Open Siddur Project with a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International copyleft license.

![Blue and white synagogue tile decorated with Moorish arch and floral motif and inscribed with the Hebrew word אתה “atah” (you), Morocco, 18th century. This tile is most likely from one of the four imperial cities: Fez, Meknes, Marrakesh, or Rabat. Original record notes that this tile came from a Moroccan synagogue. Possibly from the formula “barukh atah bevo’echa uvarukh ata btsetekha” (ברוך אתה בבואך וברוך אתה בצאתך), Deuteronomy 28:6; cf. tiled inscriptions in Lazama synagogue, Marrakech. (From the Magnes Museum collection, Tile [77-275].)](https://opensiddur.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/moorish-synagogue-tile-atah-morocco-ca-18th-c-250x250.png)

Leave a Reply