In his essay, “

Even A New Siddur Can’t Close the ‘God Gap’” (in The Forward, 8/18/2009), Rabbi Saul Berman seems almost ready to give an honest critique of the siddur and the practice of t’fillah, but instead steps back to make a more general critique on modernity. The central problem Berman addresses is the problem of Jewish spiritual alienation in an age of comfort and optimism in technological and industrial progress.

Berman argues that “new and creative siddurim” will not help translate the text of the prayer into a language understandable to “modern, socially integrated” Jews. Rather, he calls for the reintroduction of “God and God’s values into the truly vibrant dimensions of our lives.”

What Berman is calling for isn’t exactly new. I think you can hear his critique of modernity, not only in a stream of sermons dating back to pious worries of the pernicious influence of the Haskala (Enlightenment). Similar worries were also expressed by Romantic Christian theologians and continue to be voiced by religious thinkers of all sorts concerned with assimilation and materialism.

What might be new is his use of the Siddur as a prop in a straw man argument. Berman chronicles a list of popular siddurim published in the last century. I don’t think any editors of these works expected their new siddur to change how Jews relate to holiness and divinity in their lives. Their more modest goal was (and remains) to simply help make Jewish liturgy more accessible to Jewish communities in their native languages and in accordance with the philosophies undergirding their communal religious identities.

As printed and bound texts prepared by others, pre-programmed siddurim, “new and creative” or old and familiar, do not permit easy modification. I hardly expect anyone to not feel alienated or bored when provided with texts written by others in different languages and different contexts. This is as true for folks well practiced in davvening thrice daily as those who visit shul once a year for Yom Kippur. Without a program of learning that helps someone become familiar with the liturgy I wouldn’t expect them to engage the texts of the siddur and prepare their rote recitation with kavvanah (intention). I wouldn’t expect them to breathe an improvisational and creative spirit into the verses they hurry to read without having some feeling of profound intimacy with the words themselves.

Like Berman, I don’t have too much hope that any of the modern siddurim he writes of will end spiritual alienation for Jews that may not know (or care) that Berman thinks they’re alienated. Neither the siddurim as currently designed, nor the practice of t’fillah as mandated in Halakha can guarantee the intimate relationship that Berman hopes is renewed in the Jewish people.

And yet, Jewish tradition does offer Jews a toolkit and a practice for engaging and growing integral relationships. I do think a new siddur can have an impact on the problem Berman tries to articulate, even for a Jew that doesn’t share Berman’s idea of God or “Godly values” as he puts it.

Berman doesn’t elaborate on how his hoped for reintroduction of values will take place, but they must begin somewhere. Considering the essential place of the siddur within the spiritual and educational toolkit provided to each and every Jew, thinking of it as part of a comprehensive program of Jewish spiritual renewal is essential. The initiation of the sons and daughters of Israel to their eponymous mission of wrestling with God begins with their wrestling with the siddur: the languages of the source texts, the translations, the instructions, and the energy to maintain and preserve the practice as an individual in a group and while practicing t’filla alone.

I have some faith that a siddur, thought of as a tool and thus open for redesign to achieve certain goals, can be useful and relevant—so long as it is user modifiable, and in an importance sense, crafted. The term “alienation” was first promulgated in the mid 19th century in connection with craft workers who through the industrial processes of mass production were “alienated” from their essential creative natures. At the Open Siddur Project, we hope to empower individuals in a collaborative online workshop where they can craft their own custom siddur, relevant to their spiritual practice.

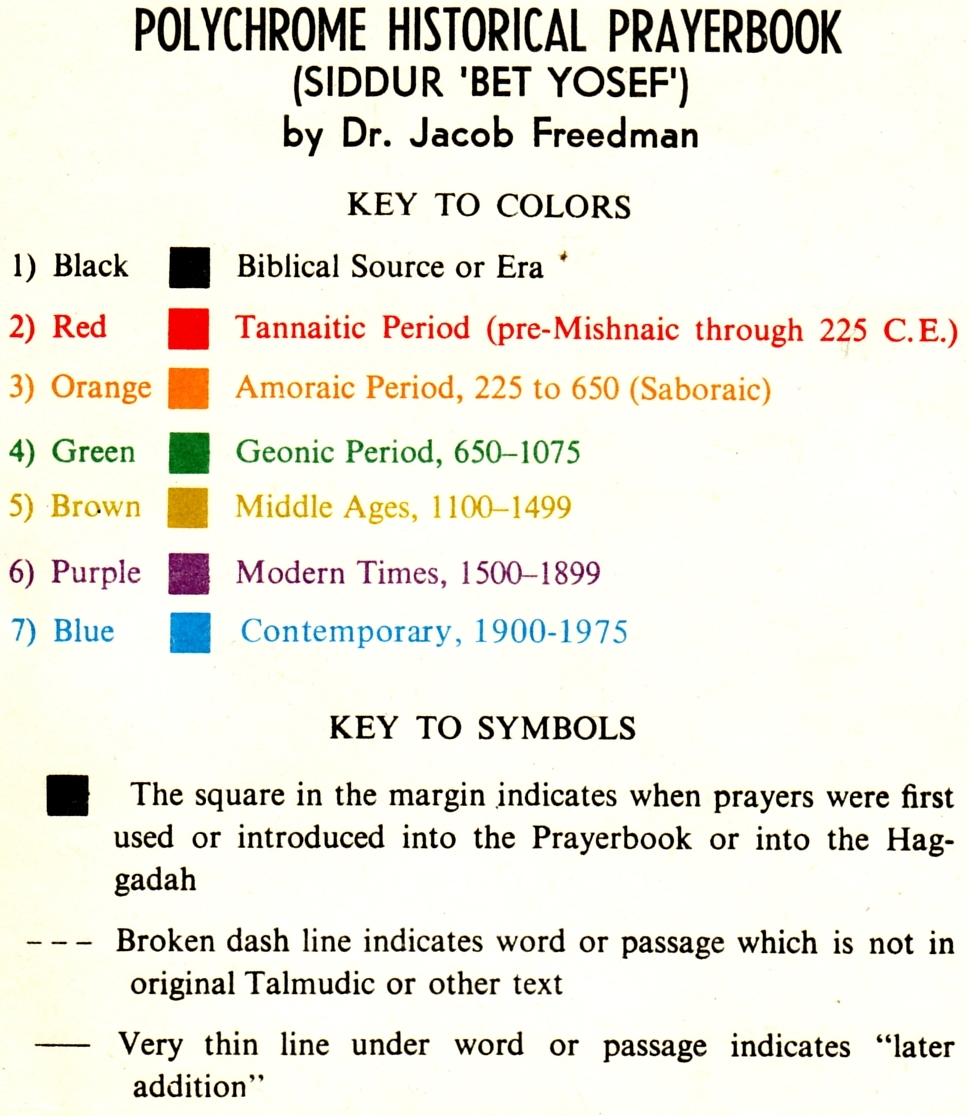

Giving an individual a choice of how verses that are tripping them up are translated, or even how the ineffable name, YHVH, and other divine names in Hebrew are represented in a siddur, can make a difference in their experience of t’fillah (prayer) for someone engaging in individual or communal prayer. Giving someone a place to share their personally authored t’fillot, meditation or commentary, or else collaborate on a translation of a medieval piyut (liturgical poem) can connect Jews to each other in a meaningful way where before they were isolated in their passion and earnest devotion. Providing historical data revealing the siddur as an aggregate of thousands of years of creatively inspired texts can help a Jew understand that their creativity and contribution is also important in this enduring conversation.

Once upon a time, Jews — Israelites — prayed from the heart — sans Siddurim. (The first example of the standing silent meditation, the Amidah, is attributed to Ḥanah the mother of the prophet Shmuel (in 1 Samuel 1:13).) What kind of siddur might we design today if our goal was to help Jews again pray from the heart? Would it be a tome full of psalms attributed to King David or might it be a sequence of exercises that reference and emphasize values that help prime our daily practice of gmillut chasadim (acts of loving-kindness) and other mitzvot? Perhaps it could be a combination of both – historically authentic and yet impressed with the meaning that only an individual can author from their heart.

Personally, I would very much like to see an attempt made to designed a siddur with this goal in mind. But, the mission of the Open Siddur is not to create a new siddur and then prescriptively offer it up as the expression of a new movment. Rather, our mission is to provide a collaborative publishing platform where any aspiring siddur maker can try their hand at crafting a siddur relevant to their practice.

I would also recommend anyone interested in taking Berman’s concern seriously to check out Aryeh Ben David’s suggestions for personalizing t’fillah in his book “The Godfile: 10 Approaches to Personalizing Prayer” (2007, Devorah Publishing). Rav Ben David has an organization that is devoted to helping both individual Jews and congregations grow in a serious practice that is engaging and nourishes integral relationships. Check out http://www.ayeka.org.il.