| Source (Judeo-Italian) | Transliteration (Judeo-Italian, romanized) | Translation (English) |

|---|---|---|

|

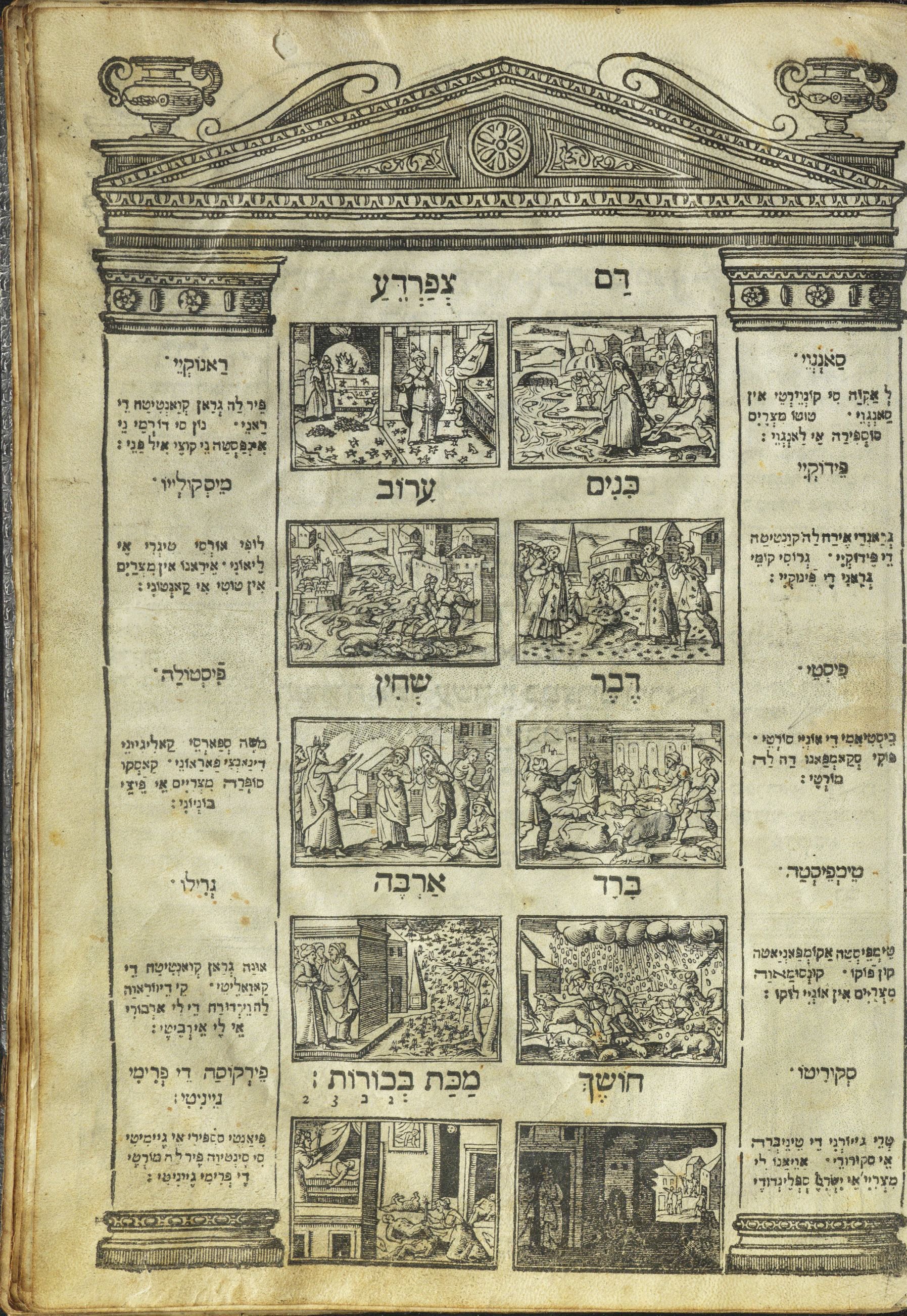

סַאנְגְוֵי

לְ אַקְוַה סִי קוֹנְוֵירְטֵי אִין סַאנְגְוֵי טוּטוֹ מִצְרָיִם סוֹסְפִּירַה אֵי לַאנְגְוֵי׃ |

Sangue

L’acqua si converte in sangue tutto Mizraim sospira e langue. |

Blood

Into blood the water turns; all of Egypt sighs and yearns. |

|

רַאנוֹקְיֵי

פֵּיר לַה גְרַאן קְוַאנְטִיטַה דֵי רַאנֵי נוֹן סִי דוֹרְמֵי נֵי אִינְפַּסְטַה נֵי קוֹצֶי אִיל פַּנֵי׃ |

Ranocchie

Per la gran quantità de[1] A dialectal form, used consistently throughout this entire passage. In standard Italian this would be spelled di. rane, non si dorme né inpasta[2] A dialectal form. In standard Italian this would be spelled impasta. né coce[3] A dialectal form. In standard Italian this would be spelled cuoce. il pane. |

Froggies

So many frogs upon Egypt did leap that none could bake their bread or sleep! |

|

פֵּידוֹקְיִי

גְרַאנְדֵי אֶירַה לַה קְוַנְטִיטַה דֵי פֶּידוֹקְיִי גְרוֹסִי קוֹמֵי גְרָאנִי דֵי פִּינוֹקְיִי׃ |

Pedocchi[4] A dialectal form. In standard Italian this would be spelled pidocchi.

Grande era la quantità de pedocchi, grossi come grani de pinocchi.[5] A Tuscan dialectal form. In standard Italian the more common word would be pinoli. This form is still relevant, though, seeing as it’s the source of the name of a well-known Italian fairy-tale character named after the nut of the pinetree from which he was carved. |

Head-lice

Great was the number of lice and fleas, as big as the nuts that you get from pine trees! |

|

מֵיסְקוּלְייוֹ

לוּפִּי אוֹרְסִי טִיגְרִי אֵי לֵיאוֹנִי אֵירַאנוֹ אִין מִצְרַיִם אִין טוּטִי אִי קַאנְטוֹנִי׃ |

Mescuglio[6] A dialectal form. In standard Italian this would be spelled miscuglio.

Lupi, orsi, tigri, e leoni; erano in Mizraim in tutti e cantoni. |

Mixture

Wolves, bears, tigers, lions roared throughout all Egypt in every ward. |

|

פֵּיסְטֵי

בֵּיסְטִיאַמִי דֵי אוֹנְיִי סוֹרְטֵי פּוֹקִי סְקַאמְפַּאנוֹ דַה לַה מוֹרְטֶי׃ |

Peste

Bestiami de ogni sorte; pochi scampano da la[7] In standard Italian this would be written as dalla. morte. |

Plague

Livestock of every kind; escape from death few find. |

|

פִֿיסְטוֹלַה

מֹשֶׁה סְפַּארְסֵי קַאלִיגִינֵי דִינַאנְצִי פַארַאוֹנֵי קַאסְקוֹ סוֹפְּרַה מִצְרִיִּים אֵי פֵיצֵי בּוֹנְיוֹנִי׃ |

Fistola

Moscè sparse caligine dinanzi Faraone; casco sopra Mizrigìm e feze bognoni.[8] A very old-fashoned Italian word. I can’t find evidence that it’s been used much in the past three hundred years. Note also the rhyme between Faraone and bognoni which suggests some weakening of word-final vowels, a process that would also explain the usage of de. |

Fistula

Before Pharaoh Moses spread fine soot, so the Egyptians grew buboes from head to foot. |

|

טֵימְפֵּיסְטַה

טֵימְפֵּיסְטַה אַקוֹמְפַּאנְיַאטַה קוֹן פוֹקוֹ קוּנְסוּמַאוַה מִצְרִיִּים אִוֹן אוֹנְיִי לוֹקוֹ׃ |

Storm

Storm accompanied by fire consumed Egypt in every shire. |

|

|

גְרִילוֹ

אוּנַה גְרַאן קְוַאנְטִיטַה דֵי קַאוַאלֵיטֵי קֵי דֵיווֹרַאוַה לַה וֵירדוּרַה דֵי לֵי אַרְבּוֹרִי אֵי לֶי אֵירְבֶּיטֶי |

Cricket

A large quantity of locusts covered the scenery which devoured the trees and herbs’ greenery. |

|

|

סְקוּרִיטוֹ

טְרֵי גְייוֹרְנִי דֵי טֵינֵיבְּרַה אֵי סְקוּרוֹרֵי אַוֵיאַנוֹ לִי מִצְרִיִּים אֵי יִשְׂרָﭏֵ סְפְּלֶינְדוֹרֵי׃ |

Darkened

Three days of darkness and obscurity the Egyptians had; and Israel, splendor and purity. |

|

|

פֵּירְקוֹסַה דֵי פְּרִימִי גֵיינִיטִי׃

פִּיאַנְטִי סֹסְפִּירִי אֵי גֶיימִיטִי סִי סִינְטיוַה פֶּיר לַה מוֹרְטֶי דֶי פְּרִימִי גֵיינִיטִי׃ |

Percossa de primi geniti[16] An archaic form. In standard Italian this would be spelled primogeniti as one word. This is reflected in the English translation by writing “first born” as two words instead of one.

Pianti, sospiri, e gemiti si sentìva per la morte de primi geniti. |

Strike of the first born

Cries, sighs, and groans, as they mourn, were heard for the death of the first born. |

Source(s)

Notes

| 1 | A dialectal form, used consistently throughout this entire passage. In standard Italian this would be spelled di. |

|---|---|

| 2 | A dialectal form. In standard Italian this would be spelled impasta. |

| 3 | A dialectal form. In standard Italian this would be spelled cuoce. |

| 4 | A dialectal form. In standard Italian this would be spelled pidocchi. |

| 5 | A Tuscan dialectal form. In standard Italian the more common word would be pinoli. This form is still relevant, though, seeing as it’s the source of the name of a well-known Italian fairy-tale character named after the nut of the pinetree from which he was carved. |

| 6 | A dialectal form. In standard Italian this would be spelled miscuglio. |

| 7 | In standard Italian this would be written as dalla. |

| 8 | A very old-fashoned Italian word. I can’t find evidence that it’s been used much in the past three hundred years. Note also the rhyme between Faraone and bognoni which suggests some weakening of word-final vowels, a process that would also explain the usage of de. |

| 9 | A dialectal form. In standard Italian this would be spelled fuoco. |

| 10 | A dialectal form. In standard Italian this would be spelled consumava. |

| 11 | A dialectal form. In standard Italian this would be spelled luogo. |

| 12 | An archaic form. In standard Italian this would be spelled delle as one word. |

| 13 | A poetic form. In standard Italian this would be more likely alberi. |

| 14 | A dialectal form. In standard Italian this would be more likely oscurità. |

| 15 | An archaic form. In standard Italian this would be more likely avévano. |

| 16 | An archaic form. In standard Italian this would be spelled primogeniti as one word. This is reflected in the English translation by writing “first born” as two words instead of one. |