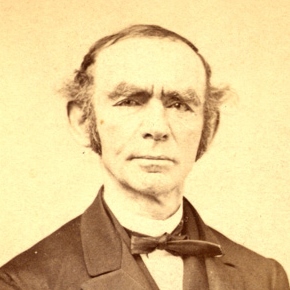

Rabbi Dr. David Einhorn was the foremost leader of the radical wing of early American Reform Judaism, and his prayer book, Olat Tamid, was the greatest expression of his vision of a Jewish people characterized by its ethical heritage—a people dispatched to sow justice among the nations, a people whose understanding of God’s unity naturally extends to include the unity of all humanity.First published in 1858, in German and Hebrew, for Einhorn’s Baltimore congregation of fellow German Jews, Olat Tamid quickly became renown not only for its innovative theology, but for its graceful writing. The history of Olat Tamid is tied to the history of American Jews, though, and before long, Einhorn’s congregants began to see themselves as Americans, rather than German-Jewish immigrants. In response, Einhorn re-issued his prayer book in English and Hebrew in 1872, and while it was adopted by over 50 congregations, it failed to achieve the same literary excellence as its German original. Because Einhorn was not working in his native tongue, it lost much of the sophisticated imagery of its predecessor, often resorting to simpler, literal translations of the Hebrew (ideologically, though, it introduced an explicit stance against a personal messiah). In 1896, 17 years after Einhorn’s death, his son-in-law, Emil G. Hirsch, the rabbi of Chicago Sinai Congregation, released a new English-Hebrew edition of Olat Tamid meant to honor Einhorn’s original German text. While Hirsch’s translation offered a faithful rendering of the German, it was marked by many tongue-twisting phrases and so many typographical errors that it was of little use to congregations.

By the time Hirsch published his edition, though, the Central Conference of American Rabbis (CCAR), the Reform rabbinical association, had published its second edition of the Union Prayer Book (UPB) using Olat Tamid as its prototype. Just a few years earlier, in 1892, the CCAR published a first version of the UPB based on Minhag Amerika, a prayer book edited by Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise, the leader of the moderate wing of the Reform movement and Einhorn’s chief antagonist. When congregants and clergy alike expressed dissatisfaction with his vision of Jewish liturgy, Wise, Reform Judaism’s institutional founder, withdrew the first edition of the UPB at great expense in favor of a new edition more closely resembling Einhorn’s work. Thus Olat Tamid became absorbed by Reform Judaism at-large, and the once profoundly influential prayer book became an instant relic.

However, the social challenges of the present day offer a uniquely rich context for re-engaging with the work of a rabbi who once had to flee for his life from Baltimore to Philadelphia because he viewed abolitionism as a Jewish imperative. As we resist the United States’s slide toward white nationalist authoritarianism against the backdrop of an international pandemic, Olat Tamid is a source of hope. The name of Einhorn’s prayer book, which means “perpetual offering,” refers to the ancient sacrifice of the Holy Temple in Jerusalem, and it is an assertion of Einhorn’s belief that our obligations to the present are deeply rooted in the past. It casts the Jewish past as a difficult but steady path toward the realization of a more perfect world. It assures us that if we work hard enough and long enough, justice will eventually prevail.

This adaptation of Einhorn’s work, Olah Ḥadashah—”a new offering”—is an attempt to bring this assurance into the present. Using modern English, gender-neutral language, and including the matriarchs in the Amidah, I hope to make a little sliver of Einhorn’s genius accessible to today’s Jews. In so doing, I hope we can find renewed purpose in our fight for justice, rooted in renewed appreciation of Judaism’s moral imperatives.

Joshua Giorgio-Rubin

South Bend, Indiana

Tammuz 5780

Recordings