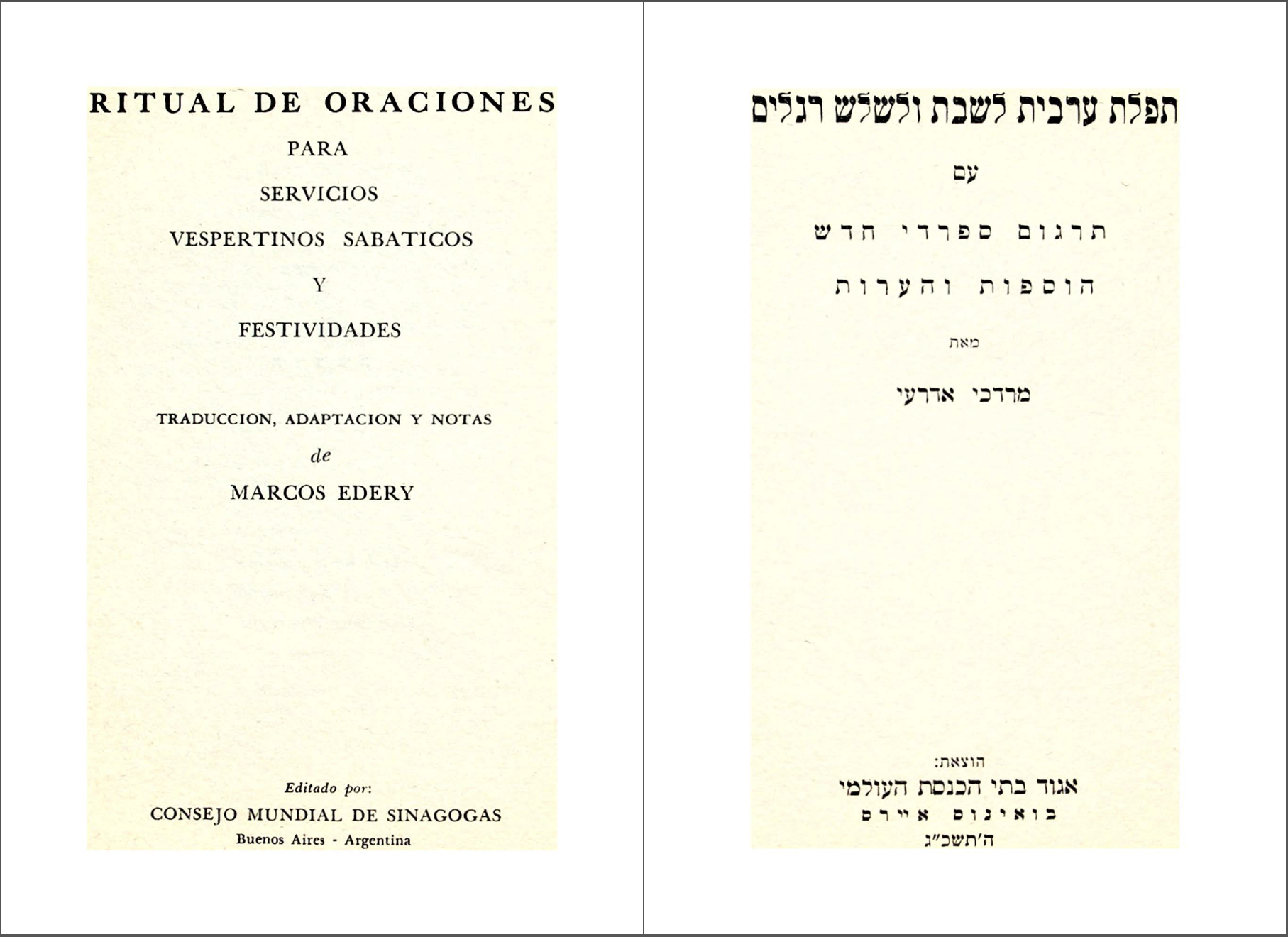

תפלת ערבית לשבת ולשלש רגלים Ritual de Oraciones para Servicios Vespertinos Sabaticos y Festividades (1963) is a bilingual Hebrew-Spanish prayerbook for Shabbat and Festival evenings compiled and translated by Rabbi Marcos Edery z”l, and published by the World Council of [Conservative/Masorti] Synagogues for Latin America under the supervision of Rabbi Marshall T. Meyer (1930-1993). Besides the liturgy of the siddur, this prayerbook includes essays concerning prayer by 20th century scholars in Spanish translation, such as Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel and Israel Abrahams.

This work is in the Public Domain in the United States by treaty according the Uruguay Round Agreements Act (1994), 50 years having passed since its publication in Argentina (the general term of copyright for works published between 1957 and 1997).

Source (Translation) Translation (English)

Director para Latinoamérica del Consejo Mundial de Sinagogas

Director for Latin America of the World Council of Synagogues

Source (Translation) Translation (English)